Alzheimer’s Disease

Topic Overview

Is this topic for you?

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of mental decline, or dementia. But dementia also has many other causes. For more information, see the topic Dementia.

What is Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease damages the brain. It causes a steady loss of memory and of how well you can speak, think, and do your daily activities.

Alzheimer’s disease gets worse over time, but how quickly this happens varies. Some people lose the ability to do daily activities in the first few years. Others may do fairly well until much later in the disease.

Mild memory loss is common in people older than 60. It may not mean that you have Alzheimer’s disease. But if your memory is getting worse, see your doctor. If it is Alzheimer’s, treatment may help.

What causes Alzheimer’s disease?

Alzheimer’s disease happens because of changes in the brain. Some of the symptoms may be related to a loss of chemical messengers in the brain, called neurotransmitters, that allow nerve cells in the brain to communicate properly.

People with Alzheimer’s disease have two things in the brain that are not normal: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles. Experts don’t know if amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are side effects of Alzheimer’s disease or part of the cause.

What are the symptoms?

For most people, the first symptom of Alzheimer’s disease is memory loss. Often the person who has a memory problem doesn’t notice it, but family and friends do. But the person with the disease may also know that something is wrong.

The symptoms of Alzheimer’s get worse slowly over time. You may:

- Have trouble making decisions.

- Be confused about what time and day it is.

- Get lost in places you know well.

- Have trouble learning and remembering new information.

- Have trouble finding the right words to say what you want to say.

- Have more trouble doing daily tasks like cooking a meal or paying bills.

A person who gets these symptoms over a few hours or days or whose symptoms suddenly get worse needs to see a doctor right away, because there may be another problem.

How is Alzheimer’s disease diagnosed?

Your doctor will ask about your past health and do a physical exam. He or she may ask you to do some simple things that test your memory and other mental skills. Your doctor may also check how well you can do daily tasks.

The exam usually includes blood tests to look for another cause of your problems. You may have tests such as CT scans and MRI scans, which look at your brain. By themselves, these tests can’t show for sure whether you have Alzheimer’s.

How is it treated?

There is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. But there are medicines that may slow symptoms down for a while and make the disease easier to live with. These medicines may not work for everyone or have a big effect. But most experts think they are worth a try.

As the disease gets worse, you may get depressed or angry and upset. The doctor may also prescribe medicines to help with these problems.

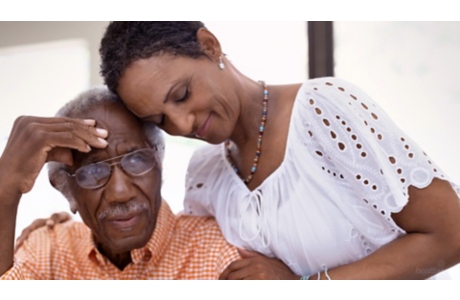

How can you help your loved one with Alzheimer’s disease?

If you are or will be taking care of a loved one with Alzheimer’s, start learning what you can expect. This can help you make the most of the person’s abilities as they change. And it can help you deal with new problems as they arise.

Work with your loved one to make decisions about the future before the disease gets worse. It’s important to write a living will and a durable power of attorney.

Your loved one will need more and more care as the disease gets worse. You may be able to give this care at home. Or you may want to think about using assisted living or a nursing home.

Ask your doctor about local resources such as support groups or other groups that can help as you care for your loved one. You can also search the Internet for online support groups. Help is available.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Alzheimer’s disease causes loss of brain cells in areas of the brain. Some of the symptoms may be related to a loss of chemical messengers in the brain, called neurotransmitters, that allow nerve cells in the brain to communicate properly.

People with Alzheimer’s disease have two things in the brain that are not normal: amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles.

- Amyloid plaques are clumps of a protein called beta amyloid. This plaque builds up around the cells in the brain that communicate with each other.

- Neurofibrillary tangles are made from a protein called tau. Normally, the tau protein helps cells communicate in the brain. In Alzheimer’s disease, the tau protein twists and tangles. The tangles clump together, and some nerve cells die, which makes communication in the brain much harder.

- As brain cells die, it shrinks. The damage to the brain eventually causes problems with memory, intelligence, judgment, language, and behavior.

Experts don’t know if amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are side effects of Alzheimer’s disease or part of the cause.

Symptoms

Memory loss is usually the first sign of Alzheimer’s disease. Having some short-term memory loss in your 60s and 70s is common, but this doesn’t mean it’s Alzheimer’s disease.

Compare these examples of normal memory problems and the types of memory problems that may be caused by Alzheimer’s disease.

|

In normal forgetfulness, the person may forget: |

In Alzheimer’s disease, the person may forget: |

|---|---|

|

Parts of an experience. |

An entire experience. |

|

Where the car is parked. |

What the car looks like. |

|

A person’s name, but remember it later. |

Ever having known a particular person. |

Alzheimer’s disease also causes changes in thinking, behavior, and personality. Close family members and friends may first notice these symptoms, although the person may also realize that something is wrong.

Following are some of the symptoms of the different stages of Alzheimer’s disease. They vary as the disease progresses. Talk to your doctor if a friend or family member has any of the signs.

Mild Alzheimer’s disease

Usually, a person with mild Alzheimer’s disease:

- Avoids new and unfamiliar situations.

- Has delayed reactions and slowed learning ability.

- Begins speaking more slowly than in the past.

- Starts using poor judgment and making inappropriate decisions.

- May have mood swings and become depressed, irritable, or restless.

These symptoms often are more obvious when the person is in a new and unfamiliar place or situation.

Some people have memory loss called mild cognitive impairment. People with this condition are at risk for Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia. But not all people with mild cognitive impairment progress to dementia.

Moderate Alzheimer’s disease

With moderate Alzheimer’s disease, a person typically:

- Has problems recognizing close friends and family.

- Becomes more restless, especially in late afternoon and at night. This is called sundowning.

- Has problems reading, writing, and dealing with numbers.

- Has trouble dressing.

- Cannot work simple appliances such as a microwave.

Severe Alzheimer’s disease

With severe Alzheimer’s disease, a person usually:

- Can no longer remember how to bathe, eat, dress, or go to the bathroom independently.

- No longer knows when to chew and swallow.

- Has trouble with balance or walking and may fall frequently.

- Becomes more confused in the evening (sundowning) and has trouble sleeping.

- Cannot communicate using words.

- Loses bowel or bladder control (incontinence).

Other conditions with similar symptoms

Early in the disease, Alzheimer’s usually doesn’t affect a person’s fine motor skills (such as the ability to button or unbutton clothes or use utensils) or sense of touch. So a person who develops motor symptoms (such as weakness or shaking hands) or sensory symptoms (such as numbness) probably has a condition other than Alzheimer’s disease. Conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, for instance, may cause motor symptoms along with dementia.

Other conditions with symptoms similar to those of Alzheimer’s disease may include:

- Dementia caused by small strokes (multi-infarct dementia).

- Thyroid problems, such as hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism.

- Depression.

- Other problems such as kidney and liver disease and some infections such as HIV (human immunodeficiency virus).

What Happens

Researchers have discovered changes that take place in the brains of people who have Alzheimer’s disease. These brain changes may cause the memory loss and decline in other mental abilities that occur with Alzheimer’s disease. It’s not fully understood why these brain changes occur in some people but not in others.

Alzheimer’s disease gets worse over time, but the course of the disease varies from person to person. Some people may still be able to function relatively well until late in the course of the disease. Others may lose the ability to do everyday activities very early on.

- The disease tends to get worse gradually. It usually starts with mild memory loss. It progresses to severe mental and functional problems and eventual death.

- Symptoms sometimes are described as occurring in early, middle, and late phases. It’s hard to predict how long each phase will last.

- The average amount of time a person lives after developing symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease is 8 to 10 years.

A person with severe dementia becomes more vulnerable to other illnesses, such as pneumonia.

What Increases Your Risk

Certain things make getting a disease more likely. These are called risk factors. Risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease include:

- Getting older. This is the main risk factor. People rarely have dementia before age 60.

- A family history of Alzheimer’s disease, especially if one or more of your parents or siblings has the disease.

- The presence of the apolipoprotein E-4 gene.

- Having Down syndrome.

- Injuries to the brain, especially more than one injury that caused you to pass out (such as a concussion from a fall, car accident, or playing a sport.)

When should you call your doctor?

Alzheimer’s disease tends to develop slowly over time. If confusion and other changes in mental abilities come on suddenly, within hours or days, the problem may be delirium. Delirium needs treatment right away.

Seek care right away if:

- Symptoms such as a shortened attention span, memory problems, or seeing or hearing things that aren’t really there (hallucinations) develop suddenly over hours to days.

- A person who has Alzheimer’s disease has a sudden, significant change in normal behavior or if symptoms suddenly become worse.

Call your doctor to schedule an appointment if:

- Symptoms such as a shortened attention span, memory problems, or false beliefs (delusions) develop gradually over a few weeks or months.

- Memory loss and other symptoms begin to interfere with the person’s work or social life or could cause injury or harm to the person.

- You need help caring for a person with Alzheimer’s disease.

Watchful waiting

If memory loss isn’t rapidly becoming worse or interfering with work, social life, or the ability to function, it may be normal age-related memory loss. Talk to your doctor if you are concerned about memory loss.

Who to see

The following health professionals can evaluate symptoms of memory loss or confusion:

- Nurse practitioner

- Physician assistant

- Family medicine physician

- Internist

- Geriatrician

- Neurologist

- Psychiatrist

A family member or friend will need to go with the person who needs to be evaluated.

Exams and Tests

Alzheimer’s disease is diagnosed after other conditions are ruled out. Your doctor will use a variety of tests to do this.

It usually is helpful to have a family member or someone in close contact with the person present at the appointment. A family member may be able to provide the best information about how a person’s day-to-day functioning, memory, and personality have changed.

Initial tests

The doctor will use a medical history and physical exam to help find out if a physical problem may be causing the person’s symptoms. Sometimes another problem can cause the same symptoms as Alzheimer’s.

The person will also have a functional status exam and a mental health assessment. During these exams, he or she will be asked to perform simple tasks.

Lab tests

Lab tests may be done to rule out other possible causes of a person’s symptoms, such as levels of certain minerals or chemicals in the blood, liver disease, abnormal thyroid levels, or nutritional problems, such as folate or vitamin B12 deficiencies. Treatment for these conditions may slow or reverse mental decline.

Blood tests that may be done include:

- Complete blood count (CBC).

- Liver function tests.

- Folate (folic acid) test.

- Vitamin B12 concentration.

- Electrolyte and blood glucose levels (sodium, potassium, creatinine, glucose, calcium).

- Thyroid function tests.

- HIV test, if the person has risk factors for HIV or the medical history suggests it.

Imaging and other tests

Other tests include:

- Brain imaging tests, such as a CT head scan or an MRI of the head.

- A lumbar puncture to test for certain proteins in the spinal fluid.

- An electroencephalogram, or EEG.

- Brain imaging studies, such as positron emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission tomography (SPECT).

In some cases, examining the brain after death is done if the family wants to confirm that the person had Alzheimer’s disease.

Treatment Overview

While there is not yet a cure for Alzheimer’s disease, you can create a care plan to maintain quality of life and help the person stay active.

As you get started, ask yourself, other family members, and your doctor these questions:

- What kind of care does the person need right now?

- Who will take care of the person in the future?

- What can the family expect as the disease progresses?

- What kind of planning needs to be done?

Care plan

Care plans may include any of the following:

- Medicines, such as cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. These medicines may temporarily help with memory and thinking problems caused by the disease.

- Regular checkups. The doctor will check the person’s response to medicine, look for new problems, see how symptoms are changing, and provide continuing education to the family. Treatment decisions often need to be revisited as the disease progresses. A person with Alzheimer’s should see the doctor every 6 months, or sooner if a problem arises.

- Helping the person remain independent and manage daily life as long as possible.

- A plan for the caregiver. Most people with Alzheimer’s disease can be cared for at home by family or friends, at least until the disease becomes severe.

See Home Treatment to learn more about helping the person remain independent, making the most of the person’s abilities, and dealing with new problems as they arise.

What to think about

An important part of treatment is finding and treating other medical problems the person may have.

- Depression occurs in nearly half of people with Alzheimer’s disease, especially those in the early stage of the disease. Helping them get treatment for depression can help them to do better with the abilities they still have.

- Hearing and vision loss, thyroid problems, kidney problems, and other conditions are common in older adults and may make Alzheimer’s worse. Treating these problems can improve quality of life and ease the burden on the caregiver.

Prevention

At this time, there is no known way to prevent Alzheimer’s disease. But there are things that may make it less likely.

Adults who are physically active may be less likely than adults who aren’t physically active to get Alzheimer’s disease or another type of dementia. Moderate activity is safe for most people, but it’s always a good idea to talk to your doctor before starting an exercise program.

Older adults who stay mentally active may be at lower risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Reading, playing cards and other games, working crossword puzzles, and even watching television or listening to the radio may help them avoid symptoms of the disease. So can going out and remaining as socially active as possible. Although this “use it or lose it” approach hasn’t been proved, no harm can come from regularly putting the brain to work.

People who eat more fruits and vegetables, high-fiber foods, fish, and omega-3 rich oils (sometimes known as the Mediterranean diet) and who eat less red meat and dairy may have some protection against dementia.

Home Treatment

Most people who have Alzheimer’s disease are cared for at home by family members and friends. Taking care of someone with the disease can be physically and emotionally draining, but there are ways to make it easier.

Home treatment involves teamwork among health professionals and caregivers to create a safe and comfortable environment and to make tasks of daily living as easy as possible. Some people with early or mild Alzheimer’s disease can be involved in planning for the future and organizing the home and daily tasks.

One of the keys to successful home care is educating yourself. You can do a lot to make the most of the person’s remaining abilities, manage the problems that develop, and improve the quality of his or her life as well as your own. Also remember that caregiving can be a positive experience for you and the person you are caring for.

Tips for caregivers

Work with the team of health professionals to:

- Make a decision about driving.

- Make sure your home is safe.

- Keep the person eating well.

- Manage sleep problems.

- Manage bladder and bowel control problems.

The team can also help you learn how to manage behavior problems. For example, you can learn ways to:

- Make the most of remaining abilities. Reinforce and support the person’s efforts to remain independent, even if tasks take more time or aren’t done perfectly.

- Help the person avoid confusion.

- Understand behavior changes.

- Manage agitation.

- Manage wandering.

- Communicate clearly.

Caregivers should remember to seek support from other family and friends. Groups such as the Alzheimer’s Association and the Dementia Advocacy and Support Network can provide not only educational materials but also information on support groups and services. For more information, see the topic Caregiver Tips.

Plan for the future

As Alzheimer’s disease progresses, you have decisions to make about medical care and legal issues.

- A nursing home or assisted living. Providing care at home usually becomes more and more challenging. The decision to place a family member in a nursing home or other facility can be a very difficult one. But sometimes nursing home placement is the best choice.

- Palliative care. This is a kind of care for people who have a serious illness. It’s different from care to cure your illness. Its goal is to improve quality of life—not only in the body but also in the mind and spirit. Talk to your doctor if you are interested in this type of care. See the topic Palliative Care.

- End-of-life care. You may want to discuss health care and other legal issues that may arise near the end of life. An advance directive or living will lets people with the disease give others their health care instructions. To learn more, see the topic Care at the End of Life.

Medications

There are no medicines that can prevent or cure Alzheimer’s disease. Medicine may help some people function better by temporarily reducing memory loss and thinking problems. Other medicines may be needed to manage behaviors or symptoms that are causing strain for the person who has Alzheimer’s disease and/or for his or her caregivers.

Medicines for memory problems

- Cholinesterase inhibitors treat symptoms of mental decline in people who have mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. They include donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine. Donepezil can be used to help those who have severe Alzheimer’s disease.

- Memantine (Namenda) treats more severe symptoms of confusion and memory loss from Alzheimer’s disease.

Because these medicines work differently, they are sometimes used together (for example, memantine and donepezil).

These medicines may temporarily help improve memory and daily functioning in some people who have Alzheimer’s disease. The improvement varies from person to person. These medicines don’t prevent the disease from getting worse. But they may slow down symptoms of mental decline.

The main decision about using these usually isn’t whether to try a medicine but when to begin and stop treatment. Treatment can be started as soon as Alzheimer’s disease is diagnosed. If the medicines are effective, they are continued until the side effects outweigh the benefits or until the person no longer responds to the medicines.

Medicines for behavior problems

Other medicines may be tried to treat anxiety, agitated or hostile behavior, sleep problems, frightening or disruptive false beliefs (delusions), suspicion of others (paranoia), or hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that aren’t there).

Before deciding to use medicine for behavior problems, try to see what is causing the behavior. If you know the cause, you may be able to find better ways of dealing with that behavior. You may be able to avoid treatment with medicine and the side effects and costs that come with it.

Medicines generally are used only for behavior problems when other treatments have failed. They may be needed if:

- A behavior is severely disruptive or harmful to the person or to others.

- Efforts to manage or reduce disruptive behavior by making changes in the person’s environment or routines have failed.

- The behavior is making the situation intolerable for the caregiver.

- The person has trouble telling the difference between what is and is not real (psychosis). Psychosis means the person has false beliefs (delusions) or hears or sees things that aren’t there (hallucinations).

What to think about

Close monitoring and regular reevaluation of the person who has Alzheimer’s disease are very important during treatment with medicine. As the disease progresses and symptoms change, the person’s medicine needs often change. If you are a caregiver for someone with Alzheimer’s disease, be alert for adverse drug reactions or side effects that further impair the person’s ability to function.

Other Treatment

Other therapies, such as light therapy, aromatherapy, and exercise, may help reduce behaviors such as agitation. But they should only be done with supervision.

Other treatment choices

- Ginkgo biloba is one of several dietary supplements promoted to improve or preserve memory. The effectiveness of these products is unclear.

- Aromatherapy oils, such as lavender, rosemary, and lemon, may reduce agitation in some people who have dementia.

- Light therapy is often used to relieve depression. It may help reduce depression, agitation, and sleeplessness associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

- Exercise, such as walking or swimming, can also relieve symptoms of depression associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Exercise is most effective when it is combined with teaching caregivers how to work through behavioral problems with the person who has Alzheimer’s disease.

Another way a caregiver can try to reduce agitation in a person who has Alzheimer’s disease is to play soothing music during meals and when the caregiver is helping with bathing.

What to think about

Other treatments for Alzheimer’s disease need further study. Their effectiveness and possible side effects aren’t yet fully known. Talk to your doctor before you decide to try any herbal therapies, supplements, or nonprescription treatments.

References

Other Works Consulted

- Albert MS, et al. (2011). The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7 (3): 270–279.

- American Psychiatric Association (2007). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. Available online: http://psychiatryonline.org/guidelines.aspx.

- California Workgroup on Guidelines for Alzheimer’s Disease Management (2008). Guideline for Alzheimer’s Disease Management. Chicago: Alzheimer’s Association. Available online: http://www.alz.org/socal/images/professional_guidelinefullreport.pdf.

- Marder K (2012). Dementia and memory loss. In JCM Brust, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment Neurology, 2nd ed., pp. 78–101. New York: NcGraw-Hill.

- McKhann GM, et al. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7 (3): 263–269.

- National Center for Health Statistics (2010). Alzheimer’s Disease. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/alzheimr.htm.

- Qaseem A, et al. (2008). Current pharmacologic treatment of dementia: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 148: 370–378.

- Remig VM, Weeden A (2012). Medical nutrition therapy and neurologic disorders. In LK Mahan et al., eds., Krause’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process, 13th ed., pp. 923–955. St Louis, MO: Saunders.

- Small SA, Mayeux R (2010). Alzheimer disease. In LP Rowland, TA Pedley, eds., Merritt’s Neurology, 12th ed., pp. 713–718. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Sperling RA, et al. (2011). Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s and Dementia, 7 (3): 280–292.

Current as of: May 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Anne C. Poinier, MD – Internal Medicine & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Elizabeth T. Russo, MD – Internal Medicine & Myron F. Weiner, MD – Geriatric Psychiatry

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.