Gastrointestinal Complications (PDQ®): Supportive care – Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information

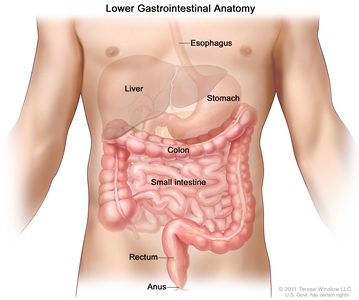

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is part of the digestive system, which processes nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and water) in foods that are eaten and helps pass waste material out of the body. The GI tract includes the stomach and intestines (bowels). The stomach is a J-shaped organ in the upper abdomen. Food moves from the throat to the stomach through a hollow, muscular tube called the esophagus. After leaving the stomach, partly-digested food passes into the small intestine and then into the large intestine. The colon (large bowel) is the first part of the large intestine and is about 5 feet long. Together, the rectum and anal canal make up the last part of the large intestine and are 6-8 inches long. The anal canal ends at the anus (the opening of the large intestine to the outside of the body).

Anatomy of the lower digestive system, showing the colon and other organs.

GI complications are common in cancer patients. Complications are medical problems that occur during a disease, or after a procedure or treatment. They may be caused by the disease, procedure, or treatment, or may have other causes. This summary describes the following GI complications and their causes and treatments:

- Constipation.

- Fecal impaction.

- Bowel obstruction.

- Diarrhea.

- Radiation enteritis.

This summary is about GI complications in adults with cancer. Treatment of GI complications in children is different than treatment for adults.

Constipation

With constipation, bowel movements are difficult or don’t happen as often as usual.

Constipation is the slow movement of stool through the large intestine. The longer it takes for the stool to move through the large intestine, the more it loses fluid and the drier and harder it becomes. The patient may be unable to have a bowel movement, have to push harder to have a bowel movement, or have fewer than their usual number of bowel movements.

Certain medicines, changes in diet, not drinking enough fluids, and being less active are common causes of constipation.

Constipation is a common problem for cancer patients. Cancer patients may become constipated by any of the usual factors that cause constipation in healthy people. These include older age, changes in diet and fluid intake, and not getting enough exercise. In addition to these common causes of constipation, there are other causes in cancer patients.

Other causes of constipation include:

Medicines

|

Diet

|

Bowel movement habits

|

Conditions that prevent activity and exercise

|

Intestinal disorders

|

Muscle and nerve disorders

|

Changes in body metabolism

|

Environment

|

Narrow colon

|

An assessment is done to help plan treatment.

The assessment includes a physical exam and questions about the patient’s usual bowel movements and how they have changed.

The following tests and procedures may be done to help find the cause of the constipation:

- Physical exam: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. The doctor will check for bowel sounds and swollen, painful abdomen.

- Digital rectal exam (DRE): An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual. In women, the vagina may also be examined.

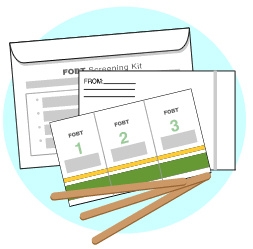

- Fecal occult blood test: A test to check stool for blood that can only be seen with a microscope. Small samples of stool are placed on special cards and returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing.

A guaiac fecal occult blood test (FOBT) checks for occult (hidden) blood in the stool. Small samples of stool are placed on a special card and returned to a doctor or laboratory for testing. - Proctoscopy: A procedure to look inside the rectum and anus to check for abnormal areas, using a proctoscope. A proctoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing the inside of the rectum and anus. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

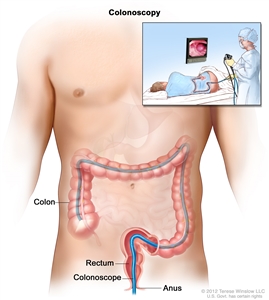

- Colonoscopy: A procedure to look inside the rectum and colon for polyps, abnormal areas, or cancer. A colonoscope is inserted through the rectum into the colon. A colonoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

Colonoscopy. A thin, lighted tube is inserted through the anus and rectum and into the colon to look for abnormal areas. - Abdominal x-ray: An x-ray of the organs inside the abdomen. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

There is no “normal” number of bowel movements for a cancer patient. Each person is different. You will be asked about bowel routines, food, and medicines:

- How often do you have a bowel movement? When and how much?

- When was your last bowel movement? What was it like (how much, hard or soft, color)?

- Was there any blood in your stool?

- Has your stomach hurt or have you had any cramps, nausea, vomiting, gas, or feeling of fullness near the rectum?

- Do you use laxatives or enemas regularly?

- What do you usually do to relieve constipation? Does this usually work?

- What kind of food do you eat?

- How much and what type of fluids do you drink each day?

- What medicines are you taking? How much and how often?

- Is this constipation a recent change in your normal habits?

- How many times a day do you pass gas?

For patients who have colostomies, care of the colostomy will be discussed.

Treating constipation is important to make the patient comfortable and to prevent more serious problems.

It’s easier to prevent constipation than to relieve it. The health care team will work with the patient to prevent constipation. Patients who take opioids may need to start taking laxatives right away to prevent constipation.

Constipation can be very uncomfortable and cause distress. If left untreated, constipation may lead to fecal impaction. This is a serious condition in which stool will not pass out of the colon or rectum. It’s important to treat constipation to prevent fecal impaction.

Prevention and treatment are not the same for every patient. Do the following to prevent and treat constipation:

- Keep a record of all bowel movements.

- Drink eight 8-ounce glasses of fluid each day. Patients who have certain conditions, such as kidney or heart disease, may need to drink less.

- Get regular exercise. Patients who cannot walk may do abdominal exercises in bed or move from the bed to a chair.

- Increase the amount of fiber in the diet by eating more of the following:

- Fruits, such as raisins, prunes, peaches, and apples.

- Vegetables, such as squash, broccoli, carrots, and celery.

- Whole grain cereals, whole grain breads, and bran.

It’s important to drink more fluids when eating more high-fiber foods, to avoid making constipation worse. Patients who have had a small or large intestinal obstruction or have had intestinal surgery (for example, a colostomy) should not eat a high-fiber diet.

- Drink a warm or hot drink about one half-hour before the usual time for a bowel movement.

- Find privacy and quiet when it is time for a bowel movement.

- Use the toilet or a bedside commode instead of a bedpan.

- Take only medicines that are prescribed by the doctor. Medicines for constipation may include bulking agents, laxatives, stool softeners, and drugs that cause the intestine to empty.

- Use suppositories or enemas only if ordered by the doctor. In some cancer patients, these treatments may lead to bleeding, infection, or other harmful side effects.

When constipation is caused by opioids, treatment may be drugs that stop the effects of the opioids or other medicines, stool softeners, enemas, and/or manual removal of stool.

Fecal Impaction

Fecal impaction is a mass of dry, hard stool that will not pass out of the colon or rectum.

Fecal impaction is dry stool that cannot pass out of the body. Patients with fecal impaction may not have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms. Instead, they may have problems with circulation, the heart, or breathing. If fecal impaction is not treated, it can get worse and cause death.

A common cause of fecal impaction is using laxatives too often.

Repeated use of laxatives in higher and higher doses makes the colon less able to respond naturally to the need to have a bowel movement. This is a common reason for fecal impaction. Other causes include:

- Opioid pain medicines.

- Little or no activity over a long period.

- Diet changes.

- Constipation that is not treated. See the section above on causes of constipation.

Certain types of mental illness may lead to fecal impaction.

Symptoms of fecal impaction include being unable to have a bowel movement and pain in the abdomen or back.

The following may be symptoms of fecal impaction:

- Being unable to have a bowel movement.

- Having to push harder to have a bowel movement of small amounts of hard, dry stool.

- Having fewer than the usual number of bowel movements.

- Having pain in the back or abdomen.

- Urinating more or less often than usual, or being unable to urinate.

- Breathing problems, rapid heartbeat, dizziness, low blood pressure, and swollen abdomen.

- Having sudden, explosive diarrhea (as stool moves around the impaction).

- Leaking stool when coughing.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Dehydration.

- Being confused and losing a sense of time and place, with rapid heartbeat, sweating, fever, and high or low blood pressure.

These symptoms should be reported to the health care provider.

Assessment includes a physical exam and questions like those asked in the assessment of constipation.

The doctor will ask questions similar to those for the assessment of constipation:

- How often do you have a bowel movement? When and how much?

- When was your last bowel movement? What was it like (how much, hard or soft, color)?

- Was there any blood in your stool?

- Has your stomach hurt or have you had any cramps, nausea, vomiting, gas, or feeling of fullness near the rectum?

- Do you use laxatives or enemas regularly?

- What do you usually do to relieve constipation? Does this usually work?

- What kind of food do you eat?

- How much and what type of fluids do you drink each day?

- What medicines are you taking? How much and how often?

- Is this constipation a recent change in your normal habits?

- How many times a day do you pass gas?

The doctor will do a physical exam to find out if the patient has a fecal impaction. The following tests and procedures may be done:

- Physical exam: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

- X-rays: An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. To check for fecal impaction, x-rays of the abdomen or chest may be done.

- Digital rectal exam (DRE): An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for a fecal impaction, lumps, or anything else that seems unusual.

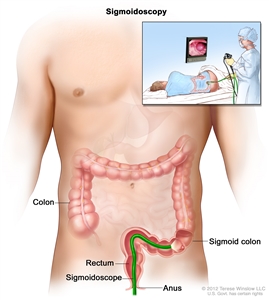

- Sigmoidoscopy: A procedure to look inside the rectum and sigmoid (lower) colon for a fecal impaction, polyps, abnormal areas, or cancer. A sigmoidoscope is inserted through the rectum into the sigmoid colon. A sigmoidoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

Sigmoidoscopy. A thin, lighted tube is inserted through the anus and rectum and into the lower part of the colon to look for abnormal areas. - Blood tests: Tests done on a sample of blood to measure the amount of certain substances in the blood or to count different types of blood cells. Blood tests may be done to look for signs of disease or agents that cause disease, to check for antibodies or tumor markers, or to see how well treatments are working.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG): A test that shows the activity of the heart. Small electrodes are placed on the skin of the chest, wrists, and ankles and are attached to an electrocardiograph. The electrocardiograph makes a line graph that shows changes in the electrical activity of the heart over time. The graph can show abnormal conditions, such as blocked arteries, changes in electrolytes (particles with electrical charges), and changes in the way electrical currents pass through the heart tissue.

A fecal impaction is usually treated with an enema.

The main treatment for impaction is to moisten and soften the stool so it can be removed or passed out of the body. This is usually done with an enema. Enemas are given only as prescribed by the doctor since too many enemas can damage the intestine. Stool softeners or glycerin suppositories may be given to make the stool softer and easier to pass. Some patients may need to have stool manually removed from the rectum after it is softened.

Laxatives that cause the stool to move are not used because they can also damage the intestine.

Bowel Obstruction

A bowel obstruction is a blockage of the small or large intestine by something other than fecal impaction.

Bowel obstructions (blockages) keep the stool from moving through the small or large intestines. They may be caused by a physical change or by conditions that stop the intestinal muscles from moving normally. The intestine may be partly or completely blocked. Most obstructions occur in the small intestine.

Physical changes

- The intestine may become twisted or form a loop, closing it off and trapping stool.

- Inflammation, scar tissue from surgery, and hernias can make the intestine too narrow.

- Tumors growing inside or outside the intestine can cause it to be partly or completely blocked.

If the intestine is blocked by physical causes, it may decrease blood flow to blocked parts. Blood flow needs to be corrected or the affected tissue may die.

Conditions that affect the intestinal muscle

- Paralysis (loss of ability to move).

- Blocked blood vessels going to the intestine.

- Too little potassium in the blood.

The most common cancers that cause bowel obstructions are cancers of the colon, stomach, and ovary.

Other cancers, such as lung and breast cancers and melanoma, can spread to the abdomen and cause bowel obstruction. Patients who have had surgery on the abdomen or radiation therapy to the abdomen have a higher risk of a bowel obstruction. Bowel obstructions are most common during the advanced stages of cancer.

Assessment includes a physical exam and imaging tests.

The following tests and procedures may be done to diagnose a bowel obstruction:

- Physical exam: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. The doctor will check to see if the patient has abdominal pain, vomiting, or any movement of gas or stool in the bowel.

- Complete blood count (CBC): A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

- Electrolyte panel: A blood test that measures the levels of electrolytes, such as sodium, potassium, and chloride.

- Urinalysis: A test to check the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells.

- Abdominal x-ray: An x-ray of the organs inside the abdomen. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

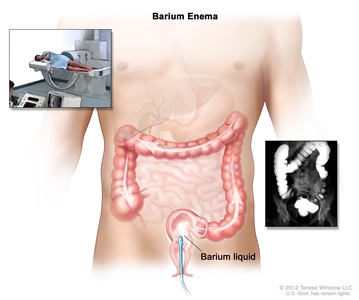

- Barium enema: A series of x-rays of the lower gastrointestinal tract. A liquid that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound) is put into the rectum. The barium coats the lower gastrointestinal tract and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called a lower GI series. This test may show what part of the intestine is blocked.

Barium enema procedure. The patient lies on an x-ray table. Barium liquid is put into the rectum and flows through the colon. X-rays are taken to look for abnormal areas.

Treatment is different for acute and chronic bowel obstructions.

Acute bowel obstruction

Acute bowel obstructions occur suddenly, may have not occurred before, and are not long-lasting. Treatment may include the following:

- Fluid replacement therapy: A treatment to get the fluids in the body back to normal amounts. Intravenous (IV) fluids may be given and medicines may be prescribed.

- Electrolyte correction: A treatment to get the right amounts of chemicals in the blood, such as sodium, potassium, and chloride. Fluids with electrolytes may be given by infusion.

- Blood transfusion: A procedure in which a person is given an infusion of whole blood or parts of blood.

- Nasogastric or colorectal tube: A nasogastric tube is inserted through the nose and esophagus into the stomach. A colorectal tube is inserted through the rectum into the colon. This is done to decrease swelling, remove fluid and gas buildup, and relieve pressure.

- Surgery: Surgery to relieve the obstruction may be done if it causes serious symptoms that are not relieved by other treatments.

Patients with symptoms that keep getting worse will have follow-up exams to check for signs and symptoms of shock and to make sure the obstruction isn’t getting worse.

Chronic, malignant bowel obstruction

Chronic bowel obstructions keep getting worse over time. Patients who have advanced cancer may have chronic bowel obstructions that cannot be removed with surgery. The intestine may be blocked or narrowed in more than one place or the tumor may be too large to remove completely. Treatments include the following:

- Surgery: The obstruction is removed to relieve pain and improve the patient’s quality of life.

- Stent: A metal tube inserted into the intestine to open the area that is blocked.

- Gastrostomy tube: A tube inserted through the wall of the abdomen directly into the stomach. The gastrostomy tube can relieve fluid and air build-up in the stomach and allow medications and liquids to be given directly into the stomach by pouring them down the tube. A drainage bag with a valve may also be attached to the gastrostomy tube. When the valve is open, the patient may be able to eat or drink by mouth and the food drains directly into the bag. This gives the patient the experience of tasting the food and keeping the mouth moist. Solid food is avoided because it may block the tubing to the drainage bag.

- Medicines: Injections or infusions of medicines for pain, nausea and vomiting, and/or to make the intestines empty. This may be prescribed for patients who cannot be helped with a stent or gastrostomy tube.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is frequent, loose, and watery bowel movements.

Diarrhea is frequent, loose, and watery bowel movements. Acute diarrhea lasts more than 4 days but less than 2 weeks. Symptoms of acute diarrhea may be loose stools and passing more than 3 unformed stools in one day. Diarrhea is chronic (long-term) when it goes on for longer than 2 months.

Diarrhea can occur at any time during cancer treatment. It can be physically and emotionally stressful for patients who have cancer.

In cancer patients, the most common cause of diarrhea is cancer treatment.

Causes of diarrhea in cancer patients include the following:

- Cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy, targeted therapy, radiation therapy, bone marrow transplant, and surgery.

- Some chemotherapy and targeted therapy drugs cause diarrhea by changing how nutrients are broken down and absorbed in the small intestine. More than half of patients who receive chemotherapy have diarrhea that needs to be treated.

- Radiation therapy to the abdomen and pelvis can cause inflammation of the bowel. Patients may have problems digesting food, and have gas, bloating, cramps, and diarrhea. These symptoms may last up to 8 to 12 weeks after treatment or may not happen for months or years. Treatment may include diet changes, medicines, or surgery.

- Patients who are having radiation therapy and chemotherapy often have severe diarrhea. Hospital treatment may not be needed. Treatment may be given at an outpatient clinic or with home care. Intravenous (IV) fluids may be given or medicines may be prescribed.

- Patients who have a donor bone marrow transplant may develop graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Stomach and intestinal symptoms of GVHD include nausea and vomiting, severe abdominal pain and cramps, and watery, green diarrhea. Symptoms may show up 1 week to 3 months after the transplant.

- Surgery on the stomach or intestines.

- The cancer itself.

- Stress and anxiety from being diagnosed with cancer and having cancer treatment.

- Medical conditions and diseases other than cancer.

- Infections.

- Antibiotic therapy for certain infections. Antibiotic therapy can irritate the lining of the bowel and cause diarrhea that often does not get better with treatment.

- Laxatives.

- Fecal impaction in which the stool leaks around the blockage.

- Certain foods that are high in fiber or fat.

Assessment includes a physical exam, lab tests, and questions about diet and bowel movements.

Because diarrhea can be life-threatening, it is important to find out the cause so treatment can begin as soon as possible. The doctor may ask the following questions to help plan treatment:

- How often have you had bowel movements in the past 24 hours?

- When was your last bowel movement? What was it like (how much, how hard or soft, what color)? Was there any blood?

- Was there any blood in your stool or any rectal bleeding?

- Have you been dizzy, very drowsy, or had any cramps, pain, nausea, vomiting, or fever?

- What have you eaten? What and how much have you had to drink in the past 24 hours?

- Have you lost weight recently? How much?

- How often have you urinated in the past 24 hours?

- What medicines are you taking? How much and how often?

- Have you traveled recently?

Tests and procedures may include the following:

- Physical exam and history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken. The exam will include checking blood pressure, pulse, and breathing; checking for dryness of the skin and tissue lining the inside of the mouth; and checking for abdominal pain and bowel sounds.

- Digital rectal exam (DRE): An exam of the rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual. The exam will check for signs of fecal impaction. Stool may be collected for laboratory tests.

- Fecal occult blood test: A test to check stool for blood that can only be seen with a microscope. Small samples of stool are placed on special cards and returned to the doctor or laboratory for testing.

- Stool tests: Laboratory tests to check the water and sodium levels in stool, and to find substances that may be causing diarrhea. Stool is also checked for bacterial, fungal, or viral infections.

- Complete blood count (CBC): A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

- Electrolyte panel: A blood test that measures the levels of electrolytes, such as sodium, potassium, and chloride.

- Urinalysis: A test to check the color of urine and its contents, such as sugar, protein, red blood cells, and white blood cells.

- Abdominal x-ray: An x-ray of the organs inside the abdomen. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body. Abdominal x-rays may also be done to look for a bowel obstruction or other problems.

Treatment of diarrhea depends on what is causing it.

Treatment depends on the cause of the diarrhea. The doctor may make changes in medicines, diet, and/or fluids.

- A change in the use of laxatives may be needed.

- Medicine to treat diarrhea may be prescribed to slow down the intestines, decrease fluid secreted by the intestines, and help nutrients be absorbed.

- Diarrhea caused by cancer treatment may be treated by changes in diet. Eat small frequent meals and avoid the following foods:

- Milk and dairy products.

- Spicy foods.

- Alcohol.

- Foods and drinks that have caffeine.

- Certain fruit juices.

- Foods and drinks that cause gas.

- Foods high in fiber or fat.

- A diet of bananas, rice, apples, and toast (the BRAT diet) may help mild diarrhea.

- Drinking more clear liquids may help decrease diarrhea. It is best to drink up to 3 quarts of clear fluids a day. These include water, sports drinks, broth, weak decaffeinated tea, caffeine-free soft drinks, clear juices, and gelatin. For severe diarrhea, the patient may need intravenous (IV) fluids or other forms of IV nutrition.

- Diarrhea caused by graft-versus-host-disease (GVHD) is often treated with a special diet. Some patients may need long-term treatment and diet management.

- Probiotics may be recommended. Probiotics are live microorganisms used as a dietary supplement to help with digestion and normal bowel function. A bacterium found in yogurt called Lactobacillus acidophilus, is the most common probiotic.

- Patients who have diarrhea with other symptoms may need fluids and medicine given by IV.

Radiation Enteritis

Radiation enteritis is inflammation of the intestine caused by radiation therapy.

Radiation enteritis is a condition in which the lining of the intestine becomes swollen and inflamed during or after radiation therapy to the abdomen, pelvis, or rectum. The small and large intestine are very sensitive to radiation. The larger the dose of radiation, the more damage may be done to normal tissue. Most tumors in the abdomen and pelvis need large doses of radiation. Almost all patients receiving radiation to the abdomen, pelvis, or rectum will have enteritis.

Radiation therapy to kill cancer cells in the abdomen and pelvis affects normal cells in the lining of the intestines. Radiation therapy stops the growth of cancer cells and other fast-growing cells. Since normal cells in the lining of the intestines grow quickly, radiation treatment to that area can stop those cells from growing. This makes it hard for tissue to repair itself. As cells die and are not replaced, gastrointestinal problems occur over the next few days and weeks.

Doctors are studying whether the order that radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and surgery are given affects how severe the enteritis will be.

Symptoms may begin during radiation therapy or months to years later.

Radiation enteritis may be acute or chronic:

- Acute radiation enteritis occurs during radiation therapy and may last up to 8 to 12 weeks after treatment stops.

- Chronic radiation enteritis may appear months to years after radiation therapy ends, or it may begin as acute enteritis and keep coming back.

The total dose of radiation and other factors affect the risk of radiation enteritis.

Only 5% to 15% of patients treated with radiation to the abdomen will have chronic problems. The amount of time the enteritis lasts and how severe it is depend on the following:

- The total dose of radiation received.

- The amount of normal intestine treated.

- The tumor size and how much it has spread.

- If chemotherapy was given at the same time as the radiation therapy.

- If radiation implants were used.

- If the patient has high blood pressure, diabetes, pelvic inflammatory disease, or poor nutrition.

- If the patient has had surgery to the abdomen or pelvis.

Acute and chronic enteritis have symptoms that are a lot alike.

Patients with acute enteritis may have the following symptoms:

- Nausea.

- Vomiting.

- Abdominal cramps.

- Frequent urges to have a bowel movement.

- Rectal pain, bleeding, or mucus in the stool.

- Watery diarrhea.

- Feeling very tired.

Symptoms of acute enteritis usually go away 2 to 3 weeks after treatment ends.

Symptoms of chronic enteritis usually appear 6 to 18 months after radiation therapy ends. It can be hard to diagnose. The doctor will first check to see if the symptoms are being caused by a recurrent tumor in the small intestine. The doctor will also need to know the patient’s full history of radiation treatments.

Patients with chronic enteritis may have the following signs and symptoms:

- Abdominal cramps.

- Bloody diarrhea.

- Frequent urges to have a bowel movement.

- Greasy and fatty stools.

- Weight loss.

- Nausea.

Assessment of radiation enteritis includes a physical exam and questions for the patient.

Patients will be given a physical exam and be asked questions about the following:

- Usual pattern of bowel movements.

- Pattern of diarrhea:

- When it started.

- How long it has lasted.

- How often it occurs.

- Amount and type of stools.

- Other symptoms with the diarrhea (such as gas, cramping, bloating, urgency, bleeding, and rectal soreness).

- Nutrition health:

- Height and weight.

- Usual eating habits.

- Changes in eating habits.

- Amount of fiber in the diet.

- Signs of dehydration (such as poor skin tone, increased weakness, or feeling very tired).

- Stress levels and ability to cope.

- Changes in lifestyle caused by the enteritis.

Treatment depends on whether the radiation enteritis is acute or chronic.

Acute radiation enteritis

Treatment of acute enteritis includes treating the symptoms. The symptoms usually get better with treatment, but if symptoms get worse, then cancer treatment may have to be stopped for a while.

Treatment of acute radiation enteritis may include the following:

- Medicines to stop diarrhea.

- Opioids to relieve pain.

- Steroid foams to relieve rectal inflammation.

- Pancreatic enzyme replacement for patients who have pancreatic cancer. A decrease in pancreatic enzymes can cause diarrhea.

- Diet changes. Intestines damaged by radiation therapy may not make enough of certain enzymes needed for digestion, especially lactase. Lactase is needed to digest lactose, which is found in milk and milk products. A lactose-free, low-fat, and low-fiber diet may help to control symptoms of acute enteritis.

- Foods to avoid:

- Milk and milk products, except buttermilk, yogurt, and lactose-free milkshake supplements, such as Ensure.

- Whole-bran bread and cereal.

- Nuts, seeds, and coconut.

- Fried, greasy, or fatty foods.

- Fresh and dried fruit and some fruit juices (such as prune juice).

- Raw vegetables.

- Rich pastries.

- Popcorn, potato chips, and pretzels.

- Strong spices and herbs.

- Chocolate, coffee, tea, and soft drinks with caffeine.

- Alcohol and tobacco.

- Foods to choose:

- Fish, poultry, and meat that are broiled or roasted.

- Bananas.

- Applesauce and peeled apples.

- Apple and grape juices.

- White bread and toast.

- Macaroni and noodles.

- Baked, boiled, or mashed potatoes.

- Cooked vegetables that are mild, such as asparagus tips, green and waxed beans, carrots, spinach, and squash.

- Mild processed cheese. Processed cheese may not cause problems because the lactose is removed when it is made.

- Buttermilk, yogurt, and lactose-free milkshake supplements, such as Ensure.

- Eggs.

- Smooth peanut butter.

- Helpful hints:

- Eat food at room temperature.

- Drink about 12 eight-ounce glasses of fluid a day.

- Let sodas lose their fizz before drinking them.

- Add nutmeg to food. This helps slow down movement of digested food in the intestines.

- Start a low-fiber diet on the first day of radiation therapy.

- Foods to avoid:

Chronic radiation enteritis

Treatment of chronic radiation enteritis may include the following:

- Same treatments as for acute radiation enteritis symptoms.

- Surgery. Few patients need surgery to control their symptoms. Two types of surgery may be used:

- Intestinal bypass: A procedure in which the doctor creates a new pathway for the flow of intestinal contents around the damaged tissue.

- Total intestinal resection: Surgery to completely remove the intestines.

Doctors look at the patient’s general health and the amount of damaged tissue before deciding if surgery will be needed. Healing after surgery is often slow and long-term tubefeeding may be needed. Even after surgery, many patients still have symptoms.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

About This PDQ Summary

About PDQ

Physician Data Query (PDQ) is the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI’s) comprehensive cancer information database. The PDQ database contains summaries of the latest published information on cancer prevention, detection, genetics, treatment, supportive care, and complementary and alternative medicine. Most summaries come in two versions. The health professional versions have detailed information written in technical language. The patient versions are written in easy-to-understand, nontechnical language. Both versions have cancer information that is accurate and up to date and most versions are also available in Spanish.

PDQ is a service of the NCI. The NCI is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIH is the federal government’s center of biomedical research. The PDQ summaries are based on an independent review of the medical literature. They are not policy statements of the NCI or the NIH.

Purpose of This Summary

This PDQ cancer information summary has current information about the causes and treatment of gastrointestinal complications, including constipation, impaction, bowel obstruction, diarrhea, and radiation enteritis. It is meant to inform and help patients, families, and caregivers. It does not give formal guidelines or recommendations for making decisions about health care.

Reviewers and Updates

Editorial Boards write the PDQ cancer information summaries and keep them up to date. These Boards are made up of experts in cancer treatment and other specialties related to cancer. The summaries are reviewed regularly and changes are made when there is new information. The date on each summary (“Updated”) is the date of the most recent change.

The information in this patient summary was taken from the health professional version, which is reviewed regularly and updated as needed, by the PDQ Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board.

Clinical Trial Information

A clinical trial is a study to answer a scientific question, such as whether one treatment is better than another. Trials are based on past studies and what has been learned in the laboratory. Each trial answers certain scientific questions in order to find new and better ways to help cancer patients. During treatment clinical trials, information is collected about the effects of a new treatment and how well it works. If a clinical trial shows that a new treatment is better than one currently being used, the new treatment may become “standard.” Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Clinical trials can be found online at NCI’s website. For more information, call the Cancer Information Service (CIS), NCI’s contact center, at 1-800-4-CANCER (1-800-422-6237).

Permission to Use This Summary

PDQ is a registered trademark. The content of PDQ documents can be used freely as text. It cannot be identified as an NCI PDQ cancer information summary unless the whole summary is shown and it is updated regularly. However, a user would be allowed to write a sentence such as “NCI’s PDQ cancer information summary about breast cancer prevention states the risks in the following way: [include excerpt from the summary].”

The best way to cite this PDQ summary is:

PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. PDQ Gastrointestinal Complications. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <MM/DD/YYYY>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/constipation/GI-complications-pdq. Accessed <MM/DD/YYYY>. [PMID: 26389438]

Images in this summary are used with permission of the author(s), artist, and/or publisher for use in the PDQ summaries only. If you want to use an image from a PDQ summary and you are not using the whole summary, you must get permission from the owner. It cannot be given by the National Cancer Institute. Information about using the images in this summary, along with many other images related to cancer can be found in Visuals Online. Visuals Online is a collection of more than 3,000 scientific images.

Disclaimer

The information in these summaries should not be used to make decisions about insurance reimbursement. More information on insurance coverage is available on Cancer.gov on the Managing Cancer Care page.

Contact Us

More information about contacting us or receiving help with the Cancer.gov website can be found on our Contact Us for Help page. Questions can also be submitted to Cancer.gov through the website’s E-mail Us.

Last Revised: 2019-03-07

If you want to know more about cancer and how it is treated, or if you wish to know about clinical trials for your type of cancer, you can call the NCI’s Cancer Information Service at 1-800-422-6237, toll free. A trained information specialist can talk with you and answer your questions.

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.