Unusual Cancers of Childhood Treatment (PDQ®): Treatment – Patient Information [NCI]

This information is produced and provided by the National Cancer Institute (NCI). The information in this topic may have changed since it was written. For the most current information, contact the National Cancer Institute via the Internet web site at http://cancer.gov or call 1-800-4-CANCER.

General Information About Unusual Cancers of Childhood

Unusual cancers of childhood are cancers rarely seen in children.

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare. Since 1975, the number of new cases of childhood cancer has slowly increased. Since 1975, the number of deaths from childhood cancer has decreased by more than half.

The unusual cancers discussed in this summary are so rare that most children’s hospitals are likely to see less than a handful of some types in several years. Because the unusual cancers are so rare, there is not a lot of information about what treatment works best. A child’s treatment is often based on what has been learned from treating other children. Sometimes, information is available only from reports of the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of one child or a small group of children who were given the same type of treatment.

Many different cancers are covered in this summary. They are grouped by where they are found in the body.

Tests are used to detect (find), diagnose, and stage unusual cancers of childhood.

Tests are done to detect, diagnose, and stage cancer. The tests used depend on the type of cancer. After cancer is diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread from where the cancer began to other parts of the body. The process used to find out if cancer cells have spread to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from the staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan the best treatment.

The following tests and procedures may be used to detect, diagnose, and stage cancer:

- Physical exam and health history: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Blood chemistry studies: A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain substances released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual (higher or lower than normal) amount of a substance can be a sign of disease.

- X-ray: An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film.

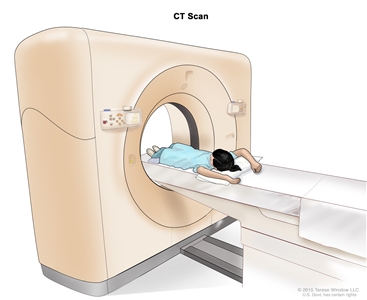

- CT scan (CAT scan): A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

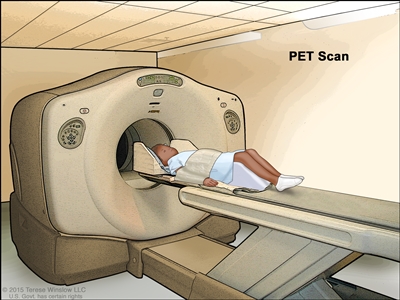

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen. The child lies on a table that slides through the CT scanner, which takes x-ray pictures of the inside of the abdomen. - PET scan (positron emission tomography scan): A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

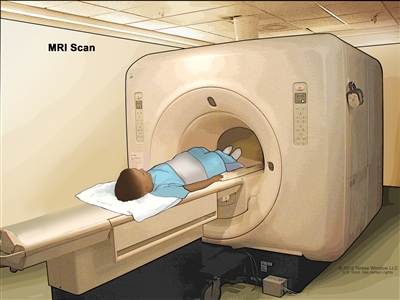

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan. The child lies on a table that slides through the PET scanner. The head rest and white strap help the child lie still. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into the child’s vein, and a scanner makes a picture of where the glucose is being used in the body. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up more glucose than normal cells do. - MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): A procedure that uses a magnet and radio waves to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. The pictures are made by a computer. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

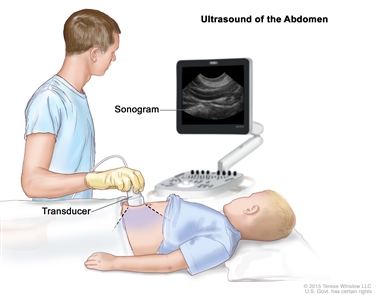

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. The child lies on a table that slides into the MRI scanner, which takes pictures of the inside of the body. The pad on the child’s abdomen helps make the pictures clearer. - Ultrasound exam: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. The picture can be printed to be looked at later.

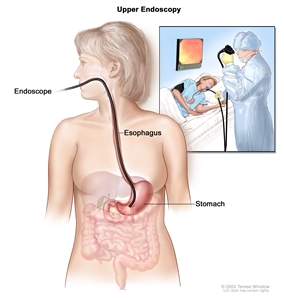

Abdominal ultrasound. An ultrasound transducer connected to a computer is pressed against the skin of the abdomen. The transducer bounces sound waves off internal organs and tissues to make echoes that form a sonogram (computer picture). - Endoscopy: A procedure to look at organs and tissues inside the body to check for abnormal areas. An endoscope is inserted through an incision (cut) in the skin or opening in the body, such as the mouth or rectum. An endoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

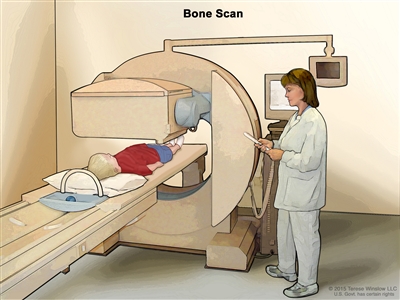

Upper endoscopy. A thin, lighted tube is inserted through the mouth to look for abnormal areas in the esophagus, stomach, and first part of the small intestine. - Bone scan: A procedure to check if there are rapidly dividing cells, such as cancer cells, in the bone. A very small amount of radioactive material is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive material collects in the bones with cancer and is detected by a scanner.

Bone scan. A small amount of radioactive material is injected into the child’s vein and travels through the blood. The radioactive material collects in the bones. As the child lies on a table that slides under the scanner, the radioactive material is detected and images are made on a computer screen. - Biopsy: The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. There are many different types of biopsy procedures. The most common types include the following:

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy: The removal of tissue or fluid using a thin needle.

- Core biopsy: The removal of tissue using a wide needle.

- Incisional biopsy: The removal of part of a lump or a sample of tissue that doesn’t look normal.

- Excisional biopsy: The removal of an entire lump or area of tissue that doesn’t look normal.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

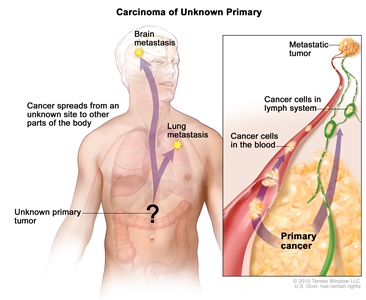

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system. The cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood. The cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if thyroid cancer spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually thyroid cancer cells. The disease is metastatic thyroid cancer, not lung cancer.

Treatment Option Overview

There are different types of treatment for children with unusual cancers.

Different types of treatments are available for children with cancer. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment.

Because cancer in children is rare, taking part in a clinical trial should be considered. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Children with unusual cancers should have their treatment planned by a team of health care providers who are experts in treating cancer in children.

Treatment will be overseen by a pediatric oncologist, a doctor who specializes in treating children with cancer. The pediatric oncologist works with other pediatric health care providers who are experts in treating children with cancer and who specialize in certain areas of medicine. These may include the following specialists:

- Pediatrician.

- Pediatric surgeon.

- Pediatric hematologist.

- Radiation oncologist.

- Pediatric nurse specialist.

- Rehabilitation specialist.

- Endocrinologist.

- Social worker.

- Psychologist.

Nine types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

Surgery is a procedure used to find out whether cancer is present, to remove cancer from the body, or to repair a body part. Palliative surgery is done to relieve symptoms caused by cancer. Surgery is also called an operation.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are different types of radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the cancer.

Proton beam radiation therapy is a type of high-energy, external radiation therapy. A radiation therapy machine aims streams of protons (tiny, invisible, positively-charged particles) at the cancer cells to kill them. This type of treatment causes less damage to nearby healthy tissue.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance that is injected into the body or sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

- 131I-MIBG (radioactive iodine) therapy is a type of internal radiation therapy used to treat pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Radioactive iodine is given by infusion. It enters the bloodstream and collects in certain kinds of tumor cells, killing them with the radiation that is given off.

The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type of cancer being treated.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping them from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can affect cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). When chemotherapy is placed directly into the cerebrospinal fluid, a body cavity such as the abdomen, or an organ, the drugs mainly affect cancer cells in those areas. Combination chemotherapy is treatment using more than one anticancer drug. The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue

High doses of chemotherapy are given to kill cancer cells. Healthy cells, including blood -forming cells, are also destroyed by the cancer treatment. Stem cell rescue is a treatment to replace the blood-forming cells. Stem cells (immature blood cells) are removed from the blood or bone marrow of the patient and are frozen and stored. After the patient completes chemotherapy, the stored stem cells are thawed and given back to the patient through an infusion. These reinfused stem cells grow into (and restore) the body’s blood cells.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is a cancer treatment that removes hormones or blocks their action and stops cancer cells from growing. Hormones are substances that are made by glands in the body and flow through the bloodstream. Some hormones can cause certain cancers to grow. If tests show that the cancer cells have places where hormones can attach (receptors), drugs, surgery, or radiation therapy is used to reduce the production of hormones or block them from working. Hormone therapy with drugs called corticosteroids may be used to treat thymoma or thymic carcinoma.

Hormone therapy with a somatostatin analogue (octreotide or lanreotide) may be used to treat neuroendocrine tumors that have spread or cannot be removed by surgery. Octreotide may also be used to treat thymoma that does not respond to other treatment. This treatment stops extra hormones from being made by the neuroendocrine tumor. Octreotide or lanreotide are somatostatin analogues which are injected under the skin or into the muscle. Sometimes a small amount of a radioactive substance is attached to the drug and the radiation also kills cancer cells. This is called peptide receptor radionuclide therapy.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy.

- Interferon: Interferon affects the division of cancer cells and can slow tumor growth. It is used to treat nasopharyngeal cancer and papillomatosis.

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes: White blood cells (T-lymphocytes) are treated in the laboratory with Epstein-Barr virus and then given to the patient to stimulate the immune system and fight cancer. EBV-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes are being studied for the treatment of nasopharyngeal cancer.

- Vaccine therapy: A cancer treatment that uses a substance or group of substances to stimulate the immune system to find the tumor and kill it. Vaccine therapy is used to treat papillomatosis.

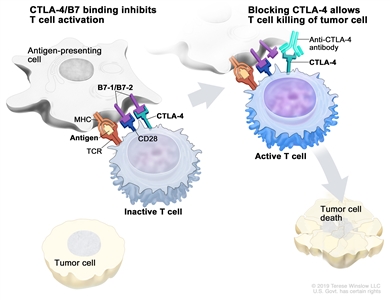

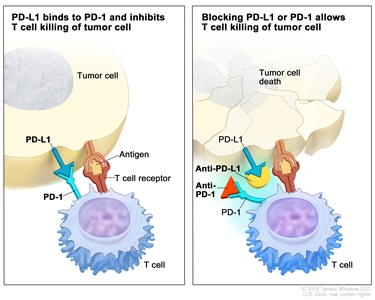

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: Some types of immune cells, such as T cells, and some cancer cells have certain proteins, called checkpoint proteins, on their surface that keep immune responses in check. When cancer cells have large amounts of these proteins, they will not be attacked and killed by T cells. Immune checkpoint inhibitors block these proteins and the ability of T cells to kill cancer cells is increased.

There are two types of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy:

- CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is a type of CTLA-4 inhibitor. Ipilimumab may be considered for the treatment of high-risk melanoma that has been completely removed during surgery. Ipilimumab is also used with nivolumab to treat certain children with colorectal cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as B7-1/B7-2 on antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CTLA-4 on T cells, help keep the body’s immune responses in check. When the T-cell receptor (TCR) binds to antigen and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) proteins on the APC and CD28 binds to B7-1/B7-2 on the APC, the T cell can be activated. However, the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 keeps the T cells in the inactive state so they are not able to kill tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of B7-1/B7-2 to CTLA-4 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-CTLA-4 antibody) allows the T cells to be active and to kill tumor cells (right panel). - PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When PD-1 attaches to another protein called PDL-1 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. PD-1 inhibitors attach to PDL-1 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Nivolumab is a type of PD-1 inhibitor. Nivolumab is used with ipilimumab to treat certain children with colorectal cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, help keep immune responses in check. The binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 keeps T cells from killing tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1) allows the T cells to kill tumor cells (right panel). immune checkpoint inhibitorsImmunotherapy uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. This animation explains one type of immunotherapy that uses immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer.

- CTLA-4 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When CTLA-4 attaches to another protein called B7 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. CTLA-4 inhibitors attach to CTLA-4 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Ipilimumab is a type of CTLA-4 inhibitor. Ipilimumab may be considered for the treatment of high-risk melanoma that has been completely removed during surgery. Ipilimumab is also used with nivolumab to treat certain children with colorectal cancer.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is closely monitoring a patient’s condition without giving any treatment until signs or symptoms appear or change. Watchful waiting may be used when the tumor is slow-growing or when it is possible the tumor may disappear without treatment.

Targeted therapy

Targeted therapy is a treatment that uses drugs or other substances to identify and attack specific cancer cells without harming normal cells. Types of targeted therapies used to treat unusual childhood cancers include the following:

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors: These targeted therapy drugs block signals needed for tumors to grow. Vandetanib and cabozantinib are used to treat medullary thyroid cancer. Sunitinib is used to treat pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma, neuroendocrine tumors, thymoma, and thymic carcinoma. Crizotinib is used to treat tracheobronchial tumors.

- mTOR inhibitors: A type of targeted therapy that stops the protein that helps cells divide and survive. Everolimus is used to treat cardiac, neuroendocrine, and islet cell tumors.

- Monoclonal antibodies: This targeted therapy uses antibodies made in the laboratory, from a single type of immune system cell. These antibodies can identify substances on cancer cells or normal substances that may help cancer cells grow. The antibodies attach to the substances and kill the cancer cells, block their growth, or keep them from spreading. Monoclonal antibodies are given by infusion. They may be used alone or to carry drugs, toxins, or radioactive material directly to cancer cells. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody used to treat papillomatosis.

- Histone methyltransferase inhibitors: This type of targeted therapy slows down the cancer cell’s ability to grow and divide. Tazemetostat is used to treat ovarian cancer. Tazemetostat is being studied in the treatment of chordomas that have recurred after treatment.

Targeted therapies are being studied in the treatment of other unusual cancers of childhood.

Embolization

Embolization is a treatment in which contrast dye and particles are injected into the hepatic artery through a catheter (thin tube). The particles block the artery, cutting off blood flow to the tumor. Sometimes a small amount of a radioactive substance is attached to the particles. Most of the radiation is trapped near the tumor to kill the cancer cells. This is called radioembolization.

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

This summary section describes treatments that are being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied. Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is a treatment in which foreign genetic material (DNA or RNA) is inserted into a person’s cells to prevent or fight disease. Gene therapy is being studied in the treatment of papillomatosis.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today’s standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Follow-up tests may be needed.

Some of the tests that were done to diagnose the cancer or to find out the stage of the cancer may be repeated. Some tests will be repeated in order to see how well the treatment is working. Decisions about whether to continue, change, or stop treatment may be based on the results of these tests.

Some of the tests will continue to be done from time to time after treatment has ended. The results of these tests can show if your child’s condition has changed or if the cancer has recurred (come back). These tests are sometimes called follow-up tests or check-ups.

Treatment for unusual cancers of childhood may cause side effects.

For information about side effects that begin during treatment for cancer, see our Side Effects page.

Side effects from cancer treatment that begin after treatment and continue for months or years are called late effects. Late effects of cancer treatment may include the following:

- Physical problems.

- Changes in mood, feelings, thinking, learning, or memory.

- Second cancers (new types of cancer).

Some late effects may be treated or controlled. It is important to talk with your child’s doctors about the possible late effects caused by some cancers and cancer treatments. (See the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for more information).

Unusual Cancers of the Head and Neck

Nasopharyngeal Cancer

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Nasopharyngeal Cancer Treatment for more information.

Esthesioneuroblastoma

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Esthesioneuroblastoma Treatment for more information.

Thyroid Tumors

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Thyroid Cancer Treatment for more information.

Oral Cavity Cancer

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Oral Cavity Cancer Treatment for more information.

Salivary Gland Tumors

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Salivary Gland Tumors Treatment for more information.

Laryngeal Cancer and Papillomatosis

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Laryngeal Tumors Treatment for more information.

Midline Tract Cancer withNUTGene Changes (NUTMidline Carcinoma)

See the PDQ summary on Childhood Midline Tract Carcinoma with NUT Gene Changes Treatment for more information.

Unusual Cancers of the Chest

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the breast. Breast cancer can occur in the breast tissue of both male and female children.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among females aged 15 to 39 years; however, less than 5% of breast cancers occur in females in this age group. Breast cancer in this age group is more aggressive and more difficult to treat than in older women. Treatments for younger and older women are similar. Younger patients with breast cancer may have genetic counseling (a discussion with a trained professional about inherited diseases) and testing for family cancer syndromes. Also, the possible effects of treatment on fertility should be considered.

Most breast tumors in children are fibroadenomas, which are benign (not cancer). Rarely, these tumors become large phyllodes tumors (cancer) and begin to grow quickly. If a benign tumor begins to grow quickly, a fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy or an excisional biopsy will be done. The tissues removed during the biopsy will be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer.

Risk Factors, Signs, and Diagnostic and Staging Tests

The risk of breast cancer is increased by the following:

- Having a personal history of a type of cancer that may spread to the breast, such as leukemia, rhabdomyosarcoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or lymphoma.

- Past treatment for another cancer, such as Hodgkin lymphoma, with radiation therapy to the breast or chest.

Other risk factors for breast cancer include the following:

- A family history of breast cancer in a mother, father, sister, or brother.

- Inherited changes in the BRCA1 or BRCA2gene or in other genes that increase the risk of breast cancer.

Breast cancer may cause any of the following signs. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- A lump or thickening in or near the breast or in the underarm area.

- A change in the size or shape of the breast.

- A dimple or puckering in the skin of the breast.

- A nipple turned inward into the breast.

- Fluid, other than breast milk, from the nipples, including blood.

- Scaly, red, or swollen skin on the breast, nipple, or areola (the dark area of skin that is around the nipple).

- Dimples in the breast that look like the skin of an orange, called peau d’orange.

Other conditions that are not breast cancer may cause these same signs.

Tests to diagnose and stage breast cancer may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- MRI.

- Ultrasound.

- PET scan.

- Blood chemistry studies.

- X-ray of the chest.

- Biopsy.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests that may be used to diagnose breast cancer include the following:

- Clinical breast exam (CBE): An exam of the breast by a doctor or other health professional. The doctor will carefully feel the breast and under the arm for lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

- Mammogram: An x-ray of the breast. When treatment for another cancer included radiation therapy to the breast or chest, it is important to have a mammogram and MRI of the breast to check for breast cancer. These should be done beginning at age 25, or 10 years after finishing radiation therapy, whichever is later.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of benign breast tumors in children may include the following:

- Watchful waiting. These tumors may disappear without treatment.

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

Treatment of breast cancer in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor, but not the whole breast. Radiation therapy may also be given.

Treatment of recurrent breast cancer in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary Breast Cancer Treatment for more information on the treatment of adolescents and young adults with breast cancer.

Lung Cancer

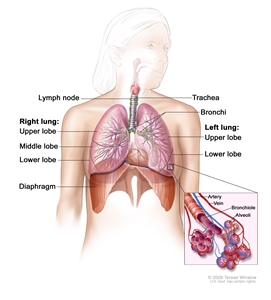

Lung cancer is a disease in which malignant cancer cells form in the tissue of the lung. The lungs are a pair of cone-shaped breathing organs in the chest. The lungs bring oxygen into the body as you breathe in. They release carbon dioxide, a waste product of the body’s cells, as you breathe out. Each lung has sections called lobes. The left lung has two lobes. The right lung is slightly larger and has three lobes. Two tubes called bronchi lead from the trachea (windpipe) to the right and left lungs. Tiny air sacs called alveoli and small tubes called bronchioles make up the inside of the lungs.

In children, most lung or airway tumors are malignant (cancer). The following are the most common primary lung or airway tumors:

- Tracheobronchial tumors.

- Pleuropulmonary blastoma.

This summary is not about cancer that has spread to the lungs from another part of the body.

Tracheobronchial Tumors

Tracheobronchial tumors begin in the inside lining of the trachea or bronchi. Most tracheobronchial tumors in children are benign and occur in the trachea or large bronchi (large airways of the lung). Sometimes, a slow-growing tracheobronchial tumor, such as inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor, becomes cancer that may spread to other parts of the body.

Anatomy of the respiratory system, showing the trachea and both lungs and their lobes and airways. Lymph nodes and the diaphragm are also shown. Oxygen is inhaled into the lungs and passes through the thin membranes of the alveoli and into the bloodstream (see inset).

Signs and Symptoms

Tracheobronchial tumors may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Dry cough.

- Wheezing.

- Trouble breathing.

- Spitting up blood from the airways or lung.

- Frequent infections in the lung, such as pneumonia.

- Feeling very tired.

- Loss of appetite or weight loss for no known reason.

Other conditions that are not tracheobronchial tumors may cause these same signs and symptoms. For example, symptoms of tracheobronchial tumors are a lot like the symptoms of asthma, which can make it hard to diagnose the tumor.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage tracheobronchial tumors may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

A biopsy of the abnormal area is usually not done because it can cause severe bleeding.

Other tests used to diagnose tracheobronchial tumors include the following:

- Bronchography: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. A contrast dye is put through the bronchoscope to make the larynx, trachea, and airways show up more clearly on x-ray film.

- Octreotide scan: A type of radionuclide scan used to find tracheobronchial tumors or cancer that has spread to the lymph nodes. A very small amount of radioactive octreotide (a hormone that attaches to carcinoid tumors) is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive octreotide attaches to the tumor and a special camera that detects radioactivity is used to show where the tumors are in the body.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) for children with tracheobronchial cancer is very good, unless the child has rhabdomyosarcoma.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

The treatment of tracheobronchial tumors depends on the type of cell the cancer formed from. Treatment of tracheobronchial tumors in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor. Sometimes a type of surgery called a sleeve resection is used. The lymph nodes and vessels where cancer has spread are also removed.

- Targeted therapy (crizotinib), for inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors that form in the trachea or bronchi.

- Chemotherapy and radiation therapy, for rhabdomyosarcoma that forms in the trachea or bronchi.

Treatment of recurrent tracheobronchial tumors in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the Neuroendocrine Tumors (Carcinoid Tumors) section of this summary for more information.

Pleuropulmonary Blastoma

Pleuropulmonary blastomas (PPBs) form in the tissue of the lung and pleura (tissue that covers the lungs and lines the inside of the chest). They can also form in the organs between the lungs including the heart, aorta, and pulmonary artery, or in the diaphragm (the main breathing muscle below the lungs). In most cases, PPBs are linked to a certain change in the DICER1gene.

There are three types of PPB:

- Type I tumors are cyst -like tumors in the lung. They are most common in children aged 2 years and younger and have a good chance of recovery. Type Ir tumors are Type I tumors that have regressed (gotten smaller) or have not grown or spread. After treatment, a Type I tumor may recur as a Type II or III tumor.

- Type II tumors are cyst-like with some solid parts. These tumors sometimes spread to the brain or other parts of the body.

- Type III tumors are solid tumors. These tumors often spread to the brain or other parts of the body.

Risk Factors, Signs and Symptoms, and Diagnostic and Staging Tests

The risk of PPB is increased by the following:

- Having a certain change in the DICER1 gene.

- Having a family history of DICER1 syndrome.

PPB may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- A cough that doesn’t go away.

- Trouble breathing.

- Fever.

- Lung infections, such as pneumonia.

- Pain in the chest or abdomen.

- Loss of appetite.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

Other conditions that are not PPB may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Tests to diagnose and stage PPB may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan of the chest and abdomen.

- PET scan.

- MRI of the head.

- Bone scan.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose PPB include the following:

- Bronchoscopy: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Thoracoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the chest to check for abnormal areas. An incision (cut) is made between two ribs, and a thoracoscope is inserted into the chest. A thoracoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer. In some cases, this procedure is used to remove part of the esophagus or lung. If the thoracoscope cannot reach certain tissues, organs, or lymph nodes, a thoracotomy may be done. In this procedure, a larger incision is made between the ribs and the chest is opened.

PPBs may spread or recur (come back) even after being removed by surgery.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) depends on the following:

- The type of pleuropulmonary blastoma.

- Whether the tumor has spread to other parts of the body at the time of diagnosis.

- Whether the tumor was completely removed by surgery.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of pleuropulmonary blastoma in children includes the following:

- Surgery to remove the whole lobe of the lung the tumor is in, with or without chemotherapy.

Treatment of recurrent pleuropulmonary blastoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

Esophageal Tumors

Esophageal tumors may be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer). Esophageal cancer is a disease in which malignant cells form in the tissues of the esophagus. The esophagus is the hollow, muscular tube that moves food and liquid from the throat to the stomach. Most esophageal tumors in children begin in the thin, flat cells that line the inside of the esophagus.

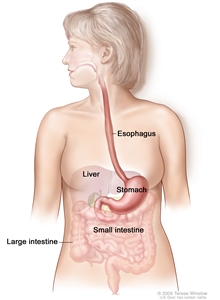

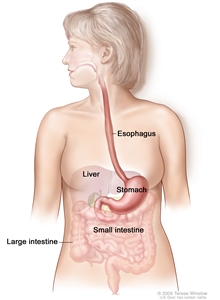

The esophagus and stomach are part of the upper gastrointestinal (digestive) system.

Risk Factors and Signs and Symptoms

The risk of esophageal cancer is increased by the following:

- Swallowing chemicals, which may burn the esophagus.

- Having gastroesophageal reflux.

- Having Barrett esophagus.

Esophageal cancer may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Trouble swallowing.

- Weight loss.

- Hoarseness and cough.

- Indigestion and heartburn.

- Vomiting with streaks of blood.

- Streaks of blood in sputum (mucus coughed up from the lungs).

Other conditions that are not esophageal cancer may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage esophageal cancer may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

- PET scan.

- MRI.

- Ultrasound.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose esophageal cancer include the following:

- Barium swallow: A series of x-rays of the esophagus and stomach. The patient drinks a liquid that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound). The liquid coats the esophagus and stomach, and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called an upper GI series.

- Esophagoscopy: A procedure to look inside the esophagus to check for abnormal areas. An esophagoscope is inserted through the mouth or nose and down the throat into the esophagus. An esophagoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer. A biopsy is usually done during an esophagoscopy. Sometimes a biopsy shows changes in the esophagus that are not cancer but may lead to cancer.

- Bronchoscopy: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Thoracoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the chest to check for abnormal areas. An incision (cut) is made between two ribs and a thoracoscope is inserted into the chest. A thoracoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer. Sometimes this procedure is used to remove part of the esophagus or lung.

Prognosis

Esophageal cancer is hard to cure because it usually cannot be completely removed by surgery.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of esophageal cancer in children may include the following:

- Radiation therapy given through a plastic or metal tube placed through the mouth into the esophagus.

- Chemotherapy.

- Surgery to remove all or part of the tumor.

Treatment of recurrent esophageal cancer in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary on adult Esophageal Cancer for more information.

Thymoma

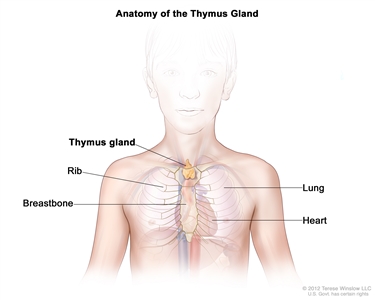

Thymoma is a tumor of the cells that cover the outside surface of the thymus. The thymus is a small organ in the upper chest under the breastbone. It is part of the lymph system and makes white blood cells, called lymphocytes, that help fight infection. Thymoma usually forms between the lungs in the front part of the chest and is often found during a chest x-ray that is done for another reason.

Anatomy of the thymus gland. The thymus gland is a small organ that lies in the upper chest under the breastbone. It makes white blood cells, called lymphocytes, which protect the body against infections.

The thymoma tumor cells look a lot like the normal cells of the thymus, grow slowly, and rarely spread beyond the thymus.

Other types of tumors, such as lymphoma or germ cell tumors, may form in the thymus but they are not considered to be thymoma.

Signs and Symptoms and Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Thymoma may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Coughing.

- Pain or a tight feeling in the chest.

- Trouble breathing.

- Trouble swallowing.

- Hoarseness.

- Fever.

- Weight loss.

- Superior vena cava syndrome.

Other conditions that are not thymoma may cause these same signs and symptoms.

People who develop thymoma often have one of the following immune system diseases or hormone disorders:

- Myasthenia gravis.

- Pure red cell aplasia.

- Hypogammaglobulinemia.

- Nephrotic syndrome.

- Scleroderma.

- Dermatomyositis.

- Lupus.

- Rheumatoid arthritis.

- Thyroiditis.

- Hyperthyroidism.

- Addison disease.

- Panhypopituitarism.

Tests to diagnose and stage thymoma may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

- PET scan.

- MRI.

- Biopsy.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) is better when the tumor has not spread to other parts of the body. Childhood thymoma is usually diagnosed before the tumor has spread.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of thymoma in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible.

- Radiation therapy, for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery or if tumor remains after surgery.

- Chemotherapy, for tumors that did not respond to other treatments.

- Hormone therapy (octreotide), for tumors that did not respond to other treatments.

- Targeted therapy (sunitinib), for tumors that did not respond to other treatments.

Treatment of recurrent thymoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary on adult Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma Treatment for more information.

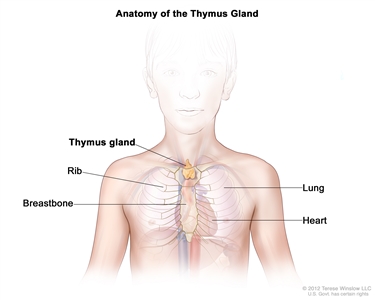

Thymic Carcinoma

Thymic carcinoma is a cancer of the cells that cover the outside surface of the thymus. The thymus is a small organ in the upper chest under the breastbone. It is part of the lymph system and makes white blood cells, called lymphocytes, that help fight infection. Thymic carcinoma usually forms between the lungs in the front part of the chest and is often found during a chest x-ray that is done for another reason.

Anatomy of the thymus gland. The thymus gland is a small organ that lies in the upper chest under the breastbone. It makes white blood cells, called lymphocytes, which protect the body against infections.

The tumor cells in thymic carcinoma do not look like the normal cells of the thymus, grow more quickly, and are more likely to spread to other parts of the body.

Other types of tumors, such as lymphoma or germ cell tumors, may form in the thymus but they are not considered to be thymic carcinoma. (See the Thymoma section above for more information).

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Thymic carcinoma can rarely be completely removed by surgery and is likely to recur (come back) after treatment.

Treatment of thymic carcinoma in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove as much of the tumor as possible.

- Radiation therapy, for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery or if tumor remains after surgery.

- Chemotherapy, for tumors that did not respond to radiation therapy.

- Targeted therapy (sunitinib), for tumors that did not respond to other treatments.

Treatment of recurrent thymic carcinoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary on adult Thymoma and Thymic Carcinoma Treatment for more information.

Heart Tumors

Most tumors that form in the heart are benign (not cancer). Benign heart tumors that may appear in children include the following:

- Rhabdomyoma: A tumor that forms in muscle made up of long fibers.

- Myxoma: A tumor that may be part of an inherited syndrome called Carney complex. (See the Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Syndromes section for more information.)

- Teratomas: A type of germ cell tumor. In the heart, these tumors form most often in the pericardium (the sac that covers the heart). Some teratomas are malignant (cancer).

- Fibroma: A tumor that forms in fiber -like tissue that holds bones, muscles, and other organs in place.

- Histiocytoid cardiomyopathy tumor: A tumor that forms in the heart cells that control heart rhythm.

- Hemangiomas: A tumor that forms in the cells that line blood vessels.

- Neurofibroma: A tumor that forms in the cells and tissues that cover nerves.

Before birth and in newborns, the most common benign heart tumors are teratomas. An inherited condition called tuberous sclerosis can cause heart tumors to form in an unborn baby (fetus) or newborn.

Malignant tumors that begin in the heart are even more rare than benign heart tumors in children. Malignant heart tumors include:

- Malignant teratoma.

- Lymphoma.

- Rhabdomyosarcoma: A cancer that forms in muscle made up of long fibers.

- Angiosarcoma: A cancer that forms in cells that line blood vessels or lymph vessels.

- Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: A cancer that usually forms in the soft tissue, but it may also form in bone.

- Leiomyosarcoma: A cancer that forms in smooth muscle cells.

- Chondrosarcoma: A cancer that usually forms in bone cartilage but very rarely can begin in the heart.

- Synovial sarcoma: A cancer that usually forms around joints but may very rarely form in the heart or sac around the heart.

- Infantile fibrosarcoma: A cancer that forms in fiber-like tissue that holds bones, muscles, and other organs in place.

Signs and Symptoms

Heart tumors may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Change in the heart’s normal rhythm.

- Trouble breathing, especially when the child is lying down.

- Pain or tightness in the middle of the chest that feels better when the child is sitting up.

- Coughing.

- Fainting.

- Feeling dizzy, tired, or weak.

- Fast heart rate.

- Swelling in the legs, ankles, or abdomen.

- Feeling anxious.

- Signs of a stroke.

- Sudden numbness or weakness of the face, arm, or leg (especially on one side of the body).

- Sudden confusion or trouble speaking or understanding.

- Sudden trouble seeing with one or both eyes.

- Sudden trouble walking or feeling dizzy.

- Sudden loss of balance or coordination.

- Sudden severe headache for no known reason.

Sometimes heart tumors do not cause any signs or symptoms.

Other conditions that are not heart tumors may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage heart tumors may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

- MRI of the heart.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose or stage heart tumors include the following:

- Echocardiogram: A procedure in which high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) are bounced off the heart and nearby tissues or organs and make echoes. A moving picture is made of the heart and heart valves as blood is pumped through the heart.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG): A recording of the heart’s electrical activity to check its rate and rhythm. A number of small pads (electrodes) are placed on the patient’s chest, arms, and legs, and are connected by wires to the EKG machine. Heart activity is then recorded as a line graph on paper. Electrical activity that is faster or slower than normal may be a sign of heart disease or damage.

- Cardiac catheterization: A procedure to look inside the blood vessels and heart for abnormal areas or cancer. A long, thin, catheter is inserted into an artery or vein in the groin, neck, or arm and threaded through the blood vessels to the heart. A sample of tissue may be removed using a special tool. A pathologist views the tissue under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of heart tumors in children may include the following:

- Watchful waiting, for rhabdomyoma, which sometimes shrinks and goes away on its own.

- Targeted therapy (everolimus) for patients who have rhabdomyoma and tuberous sclerosis.

- Chemotherapy followed by surgery (which may include removing some or all of the tumor or a heart transplant), for sarcomas.

- Surgery alone, for other tumor types.

- Radiation therapy for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery.

Treatment of recurrent heart tumors in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

Mesothelioma

Malignant mesothelioma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells are found in the following:

- Pleura: A thin layer of tissue that lines the chest cavity and covers the lungs.

- Peritoneum: A thin layer of tissue that lines the abdomen and covers most of the organs in the abdomen.

- Pericardium: A thin layer of tissue that surrounds the heart.

The tumors often spread over the surface of organs without spreading into the organ. They may spread to nearby lymph nodes or in other parts of the body. Malignant mesothelioma may also form in the testicles, but this is rare.

Risk Factors and Signs and Symptoms

Mesothelioma is sometimes a late effect of treatment for an earlier cancer, especially after treatment with radiation therapy. In adults, mesothelioma is linked to being exposed to asbestos, which was once used as building insulation. There is no information about the risk of mesothelioma in children exposed to asbestos.

Mesothelioma may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Trouble breathing.

- Cough for no known reason.

- Pain under the rib cage or pain in the chest and abdomen.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Feeling very tired.

Other conditions that are not mesothelioma may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage mesothelioma may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

- PET scan.

- MRI.

- Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose mesothelioma include the following:

- Pulmonary function test (PFT): A test to see how well the lungs are working. It measures how much air the lungs can hold and how quickly air moves into and out of the lungs. It also measures how much oxygen is used and how much carbon dioxide is given off during breathing. This is also called a lung function test.

- Bronchoscopy: A procedure to look inside the trachea and large airways in the lung for abnormal areas. A bronchoscope is inserted through the nose or mouth into the trachea and lungs. A bronchoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Thoracoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the chest to check for abnormal areas. An incision (cut) is made between two ribs and a thoracoscope is inserted into the chest. A thoracoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer. In some cases, this procedure is used to remove part of the esophagus or lung.

- Laparoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the abdomen to check for abnormal areas. Small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen and a laparoscope (thin, lighted tube) is inserted into one of the incisions. Other instruments may be inserted through the same or other incisions to perform procedures such as removing organs or taking tissue samples to be checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Cytologic exam: An exam of cells under a microscope (by a pathologist) to check for anything abnormal. For mesothelioma, fluid is taken from around the lungs or from the abdomen. A pathologist checks the cells in the fluid.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) is better when the tumor has not spread to other parts of the body.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of mesothelioma in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the part of the chest lining with cancer and some of the healthy tissue around it.

- Chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy, as palliative therapy, to relieve pain and improve quality of life.

Treatment of recurrent mesothelioma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary on adult Malignant Mesothelioma Treatment for more information.

Unusual Cancers of the Abdomen

Adrenocortical Carcinoma

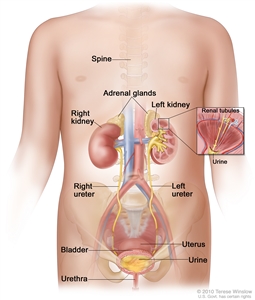

Adrenocortical carcinoma is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the outer layer of the adrenal gland. There are two adrenal glands. The adrenal glands are small and shaped like a triangle. One adrenal gland sits on top of each kidney. Each adrenal gland has two parts. The center of the adrenal gland is the adrenal medulla. The outer layer of the adrenal gland is the adrenal cortex. Adrenocortical carcinoma is also called cancer of the adrenal cortex.

Childhood adrenocortical carcinoma occurs most commonly in patients younger than 6 years or in the teen years, and more often in females.

The adrenal cortex makes important hormones that do the following:

- Balance the water and salt in the body.

- Help keep blood pressure normal.

- Help control the body’s use of protein, fat, and carbohydrates.

- Cause the body to have male or female characteristics.

Risk Factors, Signs and Symptoms, and Diagnostic and Staging Tests

The risk of adrenocortical carcinoma is increased by having a certain mutation (change) in a gene or any of the following syndromes:

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

- Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome.

- Hemihypertrophy.

Adrenocortical carcinoma may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- A lump in the abdomen.

- Pain in the abdomen or back.

- Feeling of fullness in the abdomen.

Also, a tumor of the adrenal cortex may be functioning (makes more hormones than normal) or nonfunctioning (does not make extra hormones). Most tumors of the adrenal cortex in children are functioning tumors. The extra hormones made by functioning tumors may cause certain signs or symptoms of disease and these depend on the type of hormone made by the tumor. For example, extra androgen hormone may cause both male and female children to develop masculine traits, such as body hair or a deep voice, grow faster, and have acne. Extra estrogen hormone may cause the growth of breast tissue in male children. Extra cortisol hormone may cause Cushing syndrome or hypercortisolism.

(See the PDQ summary on adult Adrenocortical Carcinoma Treatment for more information on the signs and symptoms of adrenocortical carcinoma.)

The tests and procedures used to diagnose and stage adrenocortical carcinoma depend on the patient’s symptoms. These tests and procedures may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- Blood chemistry studies.

- X-ray of the chest, abdomen, or bones.

- CT scan.

- MRI.

- PET scan.

- Ultrasound.

- Biopsy (the mass is removed during surgery and then the sample is checked for signs of cancer).

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose adrenocortical carcinoma include the following:

- Twenty-four-hour urine test: A test in which urine is collected for 24 hours to measure the amounts of cortisol or 17-ketosteroids. A higher than normal amount of these substances in the urine may be a sign of disease in the adrenal cortex.

- Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test: A test in which one or more small doses of dexamethasone are given. The level of cortisol is checked from a sample of blood or from urine that is collected for three days. This test is done to check if the adrenal gland is making too much cortisol.

- High-dose dexamethasone suppression test: A test in which one or more high doses of dexamethasone are given. The level of cortisol is checked from a sample of blood or from urine that is collected for three days. This test is done to check if the adrenal gland is making too much cortisol or if the pituitary gland is telling the adrenal glands to make too much cortisol.

- Blood hormone studies: A procedure in which a blood sample is checked to measure the amounts of certain hormones released into the blood by organs and tissues in the body. An unusual (higher or lower than normal) amount of a substance can be a sign of disease in the organ or tissue that makes it. The blood may be checked for testosterone or estrogen. A higher than normal amount of these hormones may be a sign of adrenocortical carcinoma.

- Adrenal angiography: A procedure to look at the arteries and the flow of blood near the adrenal gland. A contrast dye is injected into the adrenal arteries. As the dye moves through the blood vessel, a series of x-rays are taken to see if any arteries are blocked.

- Adrenal venography: A procedure to look at the adrenal veins and the flow of blood near the adrenal glands. A contrast dye is injected into an adrenal vein. As the contrast dye moves through the vein, a series of x-rays are taken to see if any veins are blocked. A catheter (very thin tube) may be inserted into the vein to take a blood sample, which is checked for abnormal hormone levels.

Prognosis

The prognosis (chance of recovery) is good for patients who have small tumors that have been completely removed by surgery. For other patients, the prognosis depends on the following:

- Size of the tumor.

- How quickly the cancer is growing.

- Whether there are changes in certain genes.

- Whether the tumor has spread to other parts of the body, including the lymph nodes.

- Child’s age.

- Whether the covering around the tumor broke open during surgery to remove the tumor.

- Whether the tumor was completely removed during surgery.

- Whether the child has developed masculine traits.

Adrenocortical carcinoma can spread to the liver, lung, kidney, or bone.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of adrenocortical carcinoma in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the adrenal gland and, if needed, cancer that has spread to other parts of the body. Sometimes chemotherapy is also given.

Treatment of recurrent adrenocortical carcinoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summary on adult Adrenocortical Carcinoma Treatment for more information.

Stomach (Gastric) Cancer

Stomach cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the lining of the stomach. The stomach is a J-shaped organ in the upper abdomen. It is part of the digestive system, which processes nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and water) in foods that are eaten and helps pass waste material out of the body. Food moves from the throat to the stomach through a hollow, muscular tube called the esophagus. After leaving the stomach, partly-digested food passes into the small intestine and then into the large intestine.

The esophagus and stomach are part of the upper gastrointestinal (digestive) system.

Risk Factors and Signs and Symptoms

The risk of stomach cancer is increased by the following:

- Having an infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)bacterium, which is found in the stomach.

- Having an inherited condition called familial diffuse gastric cancer.

Many patients do not have signs and symptoms until the cancer spreads. Stomach cancer may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Anemia (tiredness, dizziness, fast or irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath, pale skin).

- Stomach pain.

- Loss of appetite.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Nausea.

- Vomiting.

- Constipation or diarrhea.

- Weakness.

Other conditions that are not stomach cancer may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage stomach cancer may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the abdomen.

- Blood chemistry studies.

- CT scan.

- Biopsy.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose and stage stomach cancer include the following:

- Upper endoscopy: A procedure to look inside the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (first part of the small intestine) to check for abnormal areas. An endoscope is passed through the mouth and down the throat into the esophagus. An endoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove tissue or lymph node samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

- Barium swallow: A series of x-rays of the esophagus and stomach. The patient drinks a liquid that contains barium (a silver-white metallic compound). The liquid coats the esophagus and stomach, and x-rays are taken. This procedure is also called an upper GI series.

- Complete blood count (CBC): A procedure in which a sample of blood is drawn and checked for the following:

- The number of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- The amount of hemoglobin (the protein that carries oxygen) in the red blood cells.

- The portion of the blood sample made up of red blood cells.

Prognosis

Prognosis (chance of recovery) depends on whether the cancer has spread at the time of diagnosis and how well the cancer responds to treatment.

Stomach cancer may spread to the liver, lung, peritoneum, or to other parts of the body.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of stomach cancer in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the cancer and some healthy tissue around it.

- Surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible, followed by radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Treatment of recurrent stomach cancer in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GIST) section of this summary and the Neuroendocrine Tumors (Carcinoids) section of this summary for information about gastrointestinal carcinoids and neuroendocrine tumors.

Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the pancreas. The pancreas is a pear-shaped gland about 6 inches long. The wide end of the pancreas is called the head, the middle section is called the body, and the narrow end is called the tail. Many different kinds of tumors can form in the pancreas. Some tumors are benign (not cancer).

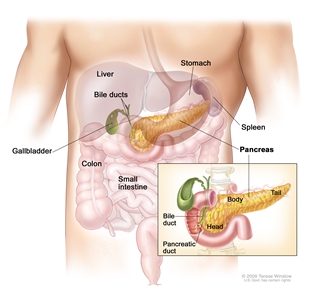

Anatomy of the pancreas. The pancreas has three areas: head, body, and tail. It is found in the abdomen near the stomach, intestines, and other organs.

The pancreas has two main jobs in the body:

- To make juices that help digest (break down) food. These juices are secreted into the small intestine.

- To make hormones that help control the sugar and salt levels in the blood. These hormones are secreted into the bloodstream.

There are four types of pancreatic cancer in children:

- Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. This is the most common type of pancreatic tumor. It most commonly affects females that are older adolescents and young adults. These slow-growing tumors have both cyst -like and solid parts. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas is unlikely to spread to other parts of the body and the prognosis is very good. Occasionally, the tumor may spread to the liver, lung, or lymph nodes.

- Pancreatoblastoma. It usually occurs in children aged 10 years or younger. Children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) syndrome have an increased risk of developing pancreatoblastoma. These slow-growing tumors often make the tumor marker alpha-fetoprotein. These tumors may also make adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and antidiuretic hormone (ADH). Pancreatoblastoma may spread to the liver, lungs, and lymph nodes. The prognosis for children with pancreatoblastoma is good.

- Islet cell tumors. These tumors are not common in children and can be benign or malignant. Islet cell tumors may occur in children with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) syndrome. The most common types of islet cell tumors are insulinomas and gastrinomas. Other types of islet cell tumors are ACTHoma and VIPoma. These tumors may make hormones, such as insulin, gastrin, ACTH, or ADH. When too much of a hormone is made, signs and symptoms of disease occur.

- Pancreatic carcinoma. Pancreatic carcinoma is very rare in children. The two types of pancreatic carcinoma are acinar cell carcinoma and ductal adenocarcinoma.

Signs and Symptoms

General signs and symptoms of pancreatic cancer may include the following:

- Fatigue.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Loss of appetite.

- Stomach discomfort.

- Lump in the abdomen.

In children, some pancreatic tumors do not secrete hormones and there are no signs and symptoms of disease. This makes it hard to diagnose pancreatic cancer early.

Pancreatic tumors that do secrete hormones may cause signs and symptoms. The signs and symptoms depend on the type of hormone being made.

If the tumor secretes insulin, signs and symptoms that may occur include the following:

- Low blood sugar. This can cause blurred vision, headache, and feeling lightheaded, tired, weak, shaky, nervous, irritable, sweaty, confused, or hungry.

- Changes in behavior.

- Seizures.

- Coma.

If the tumor secretes gastrin, signs and symptoms that may occur include the following:

- Stomach ulcers that keep coming back.

- Pain in the abdomen, which may spread to the back. The pain may come and go and it may go away after taking an antacid.

- The flow of stomach contents back into the esophagus (gastroesophageal reflux).

- Diarrhea.

Signs and symptoms caused by tumors that make other types of hormones, such as ACTH or ADH, may include the following:

- Watery diarrhea.

- Dehydration (feeling thirsty, making less urine, dry skin and mouth, headaches, dizziness, or feeling tired).

- Low sodium (salt) level in the blood (confusion, sleepiness, muscle weakness, and seizures).

- Weight loss or gain for no known reason.

- Round face and thin arms and legs.

- Feeling very tired and weak.

- High blood pressure.

- Purple or pink stretch marks on the skin.

Check with your child’s doctor if you see any of these problems in your child. Other conditions that are not pancreatic cancer may cause these same signs and symptoms.

Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Tests to diagnose and stage pancreatic cancer may include the following:

- Physical exam and health history.

- X-ray of the chest.

- CT scan.

- MRI.

- PET scan.

- Biopsy.

- Core-needle biopsy: The removal of tissue using a wide needle.

- Laparoscopy: A surgical procedure to look at the organs inside the abdomen to check for signs of disease. Small incisions (cuts) are made in the wall of the abdomen and a laparoscope (a thin, lighted tube) is inserted into one of the incisions. Other instruments may be inserted through the same or other incisions to perform procedures such as removing organs or taking tissue samples to be checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

- Laparotomy: A surgical procedure in which an incision (cut) is made in the wall of the abdomen to check the inside of the abdomen for signs of disease. The size of the incision depends on the reason the laparotomy is being done. Sometimes organs are removed or tissue samples are taken and checked under a microscope for signs of disease.

See the General Information section for a description of these tests and procedures.

Other tests used to diagnose pancreatic cancer include the following:

- Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS): A procedure in which an endoscope is inserted into the body, usually through the mouth or rectum. An endoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. A probe at the end of the endoscope is used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram. This procedure is also called endosonography.

- Somatostatin receptor scintigraphy: A type of radionuclide scan used to find pancreatic tumors. A very small amount of radioactive octreotide (a hormone that attaches to carcinoid tumors) is injected into a vein and travels through the bloodstream. The radioactive octreotide attaches to the tumor and a special camera that detects radioactivity is used to show where the tumors are in the body. This procedure is used to diagnose islet cell tumors.

Treatment

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

- Chemotherapy for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery or have spread to other parts of the body.

Treatment of pancreatoblastoma in children may include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor. A Whipple procedure may be done for tumors in the head of the pancreas.

- Chemotherapy may be given to shrink the tumor before surgery. More chemotherapy may be given after surgery for large tumors, tumors that could not initially be removed by surgery, and tumors that have spread to other parts of the body.

- Chemotherapy may be given if the tumor does not respond to treatment or comes back.

Treatment of islet cell tumors in children may include drugs to treat symptoms caused by hormones and the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

- Chemotherapy and targeted therapy (mTOR inhibitor therapy) for tumors that cannot be removed by surgery or that have spread to other parts of the body.

See the PDQ summary on adult Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (Islet Cell Tumors) Treatment for more information on pancreatic tumors.

There are few reported cases of pancreatic carcinoma in children. (See the PDQ summary on adult Pancreatic Cancer Treatment for possible treatment options.)

Treatment of recurrent pancreatic carcinoma in children may include the following:

- A clinical trial that checks a sample of the patient’s tumor for certain gene changes. The type of targeted therapy that will be given to the patient depends on the type of gene change.

See the PDQ summaries on adult Pancreatic Cancer Treatment and adult Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors (Islet Cell Tumors) Treatment for more information on pancreatic tumors.

Colorectal Cancer

Colorectal cancer is a disease in which malignant (cancer) cells form in the tissues of the colon or the rectum. The colon is part of the body’s digestive system. The digestive system removes and processes nutrients (vitamins, minerals, carbohydrates, fats, proteins, and water) from foods and helps pass waste material out of the body. The digestive system is made up of the esophagus, stomach, and the small and large intestines. The colon (large bowel) is the first part of the large intestine and is about 5 feet long. Together, the rectum and anal canal make up the last part of the large intestine and are 6-8 inches long. The anal canal ends at the anus (the opening of the large intestine to the outside of the body).

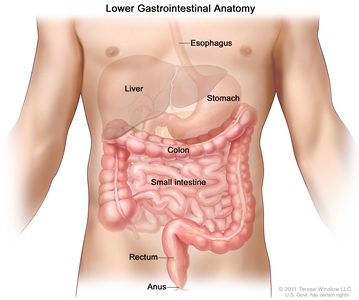

Anatomy of the lower digestive system, showing the colon and other organs.

Risk Factors, Signs and Symptoms, and Diagnostic and Staging Tests

Childhood colorectal cancer may be part of an inherited syndrome. Some colorectal cancers in young people are linked to a gene mutation that causes polyps (growths in the mucous membrane that lines the colon) to form that may turn into cancer later.

The risk of colorectal cancer is increased by having certain inherited conditions, such as:

- Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP).

- Attenuated FAP.

- MUTYH-associated polyposis.

- Lynch syndrome.

- Oligopolyposis.

- Change in the NTHL1 gene.

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome.

- Cowden syndrome.

- Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

- Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1).

Colon polyps that form in children who do not have an inherited syndrome are not linked to an increased risk of cancer.

Signs and symptoms of childhood colorectal cancer usually depend on where the tumor forms. Colorectal cancer may cause any of the following signs and symptoms. Check with your child’s doctor if your child has any of the following:

- Tumors of the rectum or lower colon may cause pain in the abdomen, constipation, or diarrhea.

- Tumors in the part of the colon on the left side of the body may cause:

- A lump in the abdomen.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

- Nausea and vomiting.

- Loss of appetite.

- Blood in the stool.

- Anemia (tiredness, dizziness, fast or irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath, pale skin).

- Tumors in the part of the colon on the right side of the body may cause:

- Pain in the abdomen.

- Blood in the stool.

- Constipation or diarrhea.

- Nausea or vomiting.

- Weight loss for no known reason.

Other conditions that are not colorectal cancer may cause these same signs and symptoms.