Acne

Topic Overview

What is acne?

Acne, or acne vulgaris, is a skin problem that starts when oil and dead skin cells clog up your pores. Some people call it blackheads, blemishes, whiteheads, pimples, or zits. When you have just a few red spots, or pimples, you have a mild form of acne. Severe acne can mean hundreds of pimples that can cover the face, neck, chest, and back. Or it can be bigger, solid, red lumps that are painful (cysts).

Acne is very common among teens. It usually gets better after the teen years. Some women who never had acne growing up will have it as an adult, often right before their menstrual periods.

How you feel about your acne may not be related to how bad it is. Some people who have severe acne are not bothered by it. Others are embarrassed or upset even though they have only a few pimples.

The good news is that there are many good treatments that can help you get acne under control.

What causes acne?

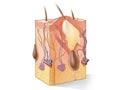

Acne starts when oil and dead skin cells clog the skin’s pores. If germs get into the pores, the result can be swelling, redness, and pus.

For most people, acne starts during the teen years. This is because hormone changes make the skin oilier after puberty starts.

Using oil-based skin products or cosmetics can make acne worse. Use skin products that don’t clog your pores. They will say “noncomedogenic” on the label.

Acne can run in families. If one of your parents had severe acne, you are more likely to have it.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of acne include whiteheads, blackheads, and pimples. These can occur on the face, neck, shoulders, back, or chest. Pimples that are large and deep are called cystic lesions. These can be painful if they get infected. They also can scar the skin.

How is acne treated?

To help control acne, keep your skin clean. Avoid skin products that clog your pores. Look for products that say “noncomedogenic” on the label. Wash your skin once or twice a day with a gentle soap or acne wash. Try not to scrub or pick at your pimples. This can make them worse and can cause scars.

If you have just a few pimples to treat, you can get an acne cream without a prescription. Look for one that has adapalene, benzoyl peroxide, or salicylic acid. These work best when used just the way the label says.

It can take time to get acne under control. But if you haven’t had good results with nonprescription products after trying them for 3 months, see your doctor. A prescription gel or skin cream may be all you need. If you are a woman, taking certain birth control pills may help.

If you have acne cysts, your doctor may suggest a stronger medicine, such as isotretinoin. This medicine works very well for some kinds of acne.

What can be done about acne scars?

There are many skin treatments, such as laser resurfacing or dermabrasion, that can help acne scars look better and feel smoother. Ask your doctor about them. The best treatment for you depends on how severe the scarring is. Your doctor may refer you to a plastic surgeon.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Decision Points focus on key medical care decisions that are important to many health problems.

Actionsets are designed to help people take an active role in managing a health condition.

Cause

There are different types of acne. The most common acne is the type that develops during the teen years. Puberty causes hormone levels to rise, especially testosterone. These changing hormones cause skin glands to start making more oil (sebum). Oil releases from the pores to protect the skin and keep it moist. Acne begins when oil mixes with dead cells and clogs the skin’s pores. Bacteria can grow in this mixture. And if this mixture leaks into nearby tissues, it causes swelling, redness, and pus. A common name for these raised bumps is pimples.

Certain medicines, such as corticosteroids or lithium, can cause acne to develop. Talk to your doctor about any medicines you are taking.

It isn’t just teens who are affected by acne. Sometimes newborns have acne because their mothers pass hormones to them just before delivery. Acne can also appear when the stress of birth causes the baby’s body to release hormones on its own. Young children and older adults also may get acne.

A few conditions of the endocrine system, such as polycystic ovary syndrome and Cushing’s syndrome, can lead to outbreaks of acne.

Symptoms

Acne develops most often on the face, neck, chest, shoulders, or back and can range from mild to severe. It can last for a few months, many years, or come and go your entire life.

Mild acne usually causes only whiteheads and blackheads. At times, these may develop into an infection in the skin pore (pimple).

Severe acne can produce hundreds of pimples that cover large areas of skin. Cystic lesions are pimples that are large and deep. These lesions are often painful and can leave scars on your skin.

Acne can lead to low self-esteem and sometimes depression. These conditions need treatment along with the acne.

What Happens

Acne develops most often in the teen and young adult years. During this time, both males and females usually produce more testosterone than at any other time in life. This hormone causes oil glands to produce more oil (sebum). The extra oil can clog pores and cause acne. Bacteria can grow in this mixture. And if the mixture leaks into nearby tissues, it causes swelling, redness, and pus (pimples).

Acne usually gets better in the adult years when your body produces less testosterone. Still, some women have premenstrual acne flare-ups well into adulthood.

What Increases Your Risk

The tendency to develop acne runs in families. You are more likely to develop severe acne if your parents had severe acne.

The risk of developing acne is highest during the teen and young adult years. These are the years when hormones such as testosterone are increasing. Women who are at the age of menstruation also are more likely to develop acne. Many women have acne flare-ups in the days just before their menstrual periods.

Acne can be irritated or made worse by:

- Wearing straps or other tight-fitting items that rub against the skin (such as a football player wearing shoulder pads), as well as using equipment that rubs against the body (such as a violin held between the cheek and shoulder). Helmets, bra straps, headbands, and turtleneck sweaters also may cause acne to get worse.

- Using skin and hair care products that contain irritating substances.

- Washing the face too often or scrubbing the face too hard. Using harsh soaps or very hot water can also cause acne to get worse.

- Experiencing a lot of stress.

- Touching the face a lot.

- Sweating a lot.

- Having hair hanging in the face, which can cause the skin to be oilier.

- Taking certain medicines, such as corticosteroids, some barbiturates, or lithium.

- Working with oils and harsh chemicals on a regular basis.

Athletes or bodybuilders who take anabolic steroids are also at risk for getting acne.footnote 1

When should you call your doctor?

Call a doctor if:

- You are concerned about your or your child’s acne.

- Your acne gets worse or does not improve after 3 months with home treatment.

- You develop scars or marks after acne heals.

- Your pimples become large and hard or filled with fluid.

- You start to have other physical symptoms, such as facial hair growth in women.

- Your acne began when you started a new medicine prescribed by a doctor.

- You have been exposed to chemicals, oils, or other substances that cause your skin to break out.

You may want to seek medical assistance sooner if there is a strong family history of acne, you are emotionally affected by acne, or you developed acne at an early age.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is a wait-and-see approach. If you get better on your own, you won’t need treatment. If you get worse, you and your doctor will decide what to do next.

Mild acne, with a few pimples that clear up on their own, may not need any treatment. But if you are worried about how much you are breaking out, see your doctor. Getting medical treatment early may prevent acne from getting worse or from causing scars.

If you have severe acne, if your acne does not clear up with home treatment, or if you develop acne scars, call your doctor.

Who to see

The following health professionals can diagnose and treat acne:

Exams and Tests

When you see a doctor about acne, you’ll have a physical exam, and your doctor will ask about your medical history. Women may be asked questions about their menstrual cycles. This information can help your doctor find out if hormones are playing a role in acne flare-ups. Most often, you won’t have any special tests to diagnose acne.

You may need other tests if your doctor suspects that acne is a symptom of another medical problem (such as higher-than-normal amounts of testosterone in a woman).

Treatment Overview

Acne treatment depends on whether you have a mild, moderate, or severe type of acne. Sometimes your doctor will combine treatments to get the best results and to avoid developing drug-resistant bacteria. Treatment could include lotions or gels you put on blemishes or sometimes entire areas of skin, such as the chest or back (topical medicines). You might also take medicines by mouth (oral medicines).

Mild acne

Treatment for mild acne (whiteheads, blackheads, or pimples) may include:

- Gentle cleansing with warm water and a mild soap, such as Dove or Cetaphil.

- Applying a topical retinoid (such as adapalene gel, or Differin).

- Applying benzoyl peroxide (such as Brevoxyl or Triaz).

- Applying salicylic acid (such as Propa pH or Stridex).

If these treatments do not work, you may want to see your doctor. Your doctor can give you a prescription for stronger lotions or creams. You may try an antibiotic lotion. Or you may try a lotion with medicine that helps to unplug your pores.

Moderate to severe acne

Sometimes acne needs treatment with stronger medicines or a combination of therapies. Deeper blemishes, such as nodules and cysts, are more likely to leave scars. As a result, your doctor may give you oral antibiotics sooner to start the healing process. This kind of acne may need a combination of several therapies. Treatment for moderate to severe acne may include:

- Applying benzoyl peroxide.

- Draining of large pimples and cysts by a doctor.

- Applying prescription antibiotic gels, creams, or lotions.

- Applying prescription retinoids.

- Applying azelaic acid.

- Taking prescription oral antibiotics.

- Taking prescription oral retinoids (such as isotretinoin).

Treatment for acne scars

There are many procedures to remove acne scars, such as laser resurfacing, chemical peels, and dermal fillers. Some scars shrink and fade with time. But if your scars bother you, talk to your doctor. He or she may refer you to a dermatologist or a plastic surgeon.

What to think about

Most treatments for acne take time. It often takes 6 to 8 weeks for acne to improve after you start treatment. Some treatments may cause acne to get worse before it gets better.

If your acne still hasn’t improved after several tries with other treatment, your doctor may recommend that you take an oral retinoid, such as isotretinoin. Doctors prescribe this medicine as a last resort, because it has some rare but serious side effects and it is expensive.

Certain low-dose birth control pills may help control acne in women who tend to have flare-ups before menstruation.

Prevention

Although you can’t prevent acne, there are steps you can take at home to keep acne from getting worse.

- Gently wash and care for your skin every day. Avoid scrubbing too hard or washing too often.

- Avoid heavy sweating if you think it causes your acne to get worse. Wash soon after activities that cause you to sweat.

- Wash your hair often if your hair is oily. Try to keep your hair off of your face.

- Avoid hair care products such as gels, mousses, cream rinses, and pomades that contain a lot of oil.

- Avoid touching your face.

- Wear soft, cotton clothing or moleskin under sports equipment. Parts of equipment, such as chin straps, can rub your skin and make your acne worse.

- Avoid exposure to oils and harsh chemicals, such as petroleum.

- Protect your skin from too much sun.

Home Treatment

Treatment at home can help reduce acne flare-ups.

- Wash your face (or other affected skin) gently one or two times a day.

- Do not squeeze pimples, because that often leads to infections, worse acne, and scars.

- Use a moisturizer to keep your skin from drying out. Choose one that says “noncomedogenic” on the label.

- Use over-the-counter medicated creams, soaps, lotions, and gels to treat your acne. Always read the label carefully to make sure you are using the product correctly.

Examples of some over-the-counter products used to treat acne include:

- Benzoyl peroxide (such as Brevoxyl or Triaz), which unplugs pores.

- Alpha hydroxy acid, which dries up blemishes and causes the top skin layer to peel. You’ll find alpha hydroxy acid in some moisturizers, cleansers, eye creams, and sunscreens.

- Salicylic acid (such as Propa pH or Stridex), which dries up blemishes and causes the top skin layer to peel.

- Tea tree oil, which kills bacteria. You’ll find tea tree oil in some gels, creams, and oils.

Some skin care products, such as those with alpha hydroxy acid, will make your skin very sensitive to ultraviolet (UV) light. Protect your skin from the sun and other sources of UV light.

Medications

Medicines can help manage the severity and frequency of acne outbreaks. A number of medicines are available. Your treatment will depend on the type of acne you have (pimples, whiteheads, blackheads, or cystic lesions). These medicines improve acne by:

- Unplugging skin pores and stopping them from getting plugged with oil (tretinoin, which is sold as Retin-A).

- Killing bacteria (antibiotics).

- Reducing the amount of skin oil (isotretinoin).

- Reducing the effects of hormones in producing acne (certain oral contraceptive pills for women).

The best medical treatment for acne often is a combination of medicines. These could include medicine that you put on your skin (topical) and medicine that you take by mouth (oral). Or you may take medicines such as clindamycin/benzoyl peroxide, a gel that contains two topical medicines.

Medicine choices

Treatment of acne depends on whether inflammation or bacteria are present. Some acne consists only of red bumps on the skin with no open sores (comedonal acne). Topical creams and lotions work best for this type of acne. But if bacteria or inflammation is present with open sores, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin may work better.

The most common types of medicines that doctors use to treat acne include:

- Benzoyl peroxide, such as Brevoxyl or Triaz.

- Salicylic acid, such as Propa pH or Stridex.

- Topical and oral antibiotics, such as clindamycin, doxycycline, erythromycin, and tetracycline.

- Topical retinoid medicines, such as adapalene (Differin), tazarotene (Tazorac), and tretinoin (Retin-A).

- Azelaic acid, such as Azelex, a topical cream.

- Isotretinoin, an oral retinoid.

- Low-dose birth control pills that contain estrogen (such as Estrostep, Ortho Tri-Cyclen, or Yaz), which work well on moderate acne in women and for premenstrual flare-ups.

- Androgen blockers, such as spironolactone. Androgen blockers can be useful in treating acne. These medicines decrease the amount of sebum (oil) made in your pores.

What to think about

If you are pregnant, talk to your doctor about whether you should take antibiotics for acne. Some antibiotics aren’t safe to take during pregnancy.

Over time, bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics, which means that the antibiotics are no longer effective at killing or controlling the bacteria causing the acne. This is called drug resistance. When this occurs, a different antibiotic may be used.

After acne is under control, you often need ongoing treatment to keep it from returning. This is the maintenance phase of treatment. Your doctor may suggest treatments other than antibiotics for long-term use, to avoid the risk of drug resistance.

Topical medicines usually have fewer and less serious side effects than oral medicines. But topical medicines may not work as well as oral medicines for severe acne.

Isotretinoin (such as Sotret) and tazarotene (Tazorac) can have serious side effects. Women who take isotretinoin or tazarotene need to use an effective birth control method, to avoid having a baby with serious birth defects.

Other Treatment

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) and other light and laser-based therapies are being used to treat acne. These include the use of blue light, red light, intense pulsed light (IPL), and infrared or pulsed dye lasers. Sometimes these therapies are used along with medicines, but they may also help people who cannot be treated with medicines.

Treatments like laser skin resurfacing and chemical peels can also help. They can make acne scars less noticeable. Dermal fillers also work well for some types of acne scars.

Your doctor may suggest other types of therapies to treat acne or acne scars.

Related Information

References

Citations

- Hall JC (2010). Seborrheic dermatitis, acne, and rosacea. In JC Hall, ed., Sauer’s Manual of Skin Diseases, 9th ed., pp. 149–159. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Other Works Consulted

- American Academy of Dermatology (2007). Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 56(4): 651–663. Also available online: http://www.aad.org/education-and-quality-care/clinical-guidelines/current-and-upcoming-guidelines.

- Del Rosso JQ (2012). Acne vulgaris and rosacea. In EG Nabel, ed., ACP Medicine, section 5, chap. 12. Hamilton, ON: BC Decker.

- Habif TP, et al. (2011). Acne. In Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment, 3rd ed., pp. 102–108. Edinburgh: Saunders.

- Purdy S, de Berker D (2011). Acne vulgaris, search date February 2010. BMJ Clinical Evidence. Available online: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Tsatsou F, Zouboulis CC (2010). Acne vulgaris. In MG Lebwohl et al., eds., Treatment of Skin Disease: Comprehensive Therapeutic Strategies, 3rd ed., pp. 6–11. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier.

- Van Durme DJ, Johnson LM (2015). Acne vulgaris. In ET Bope et al., eds., Conn’s Current Therapy 2015, pp. 219–220. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Zaenglein Al, et al. (2012). Acne vulgaris and acneiform eruptions. In LA Goldman et al., eds., Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 8th ed., vol. 1, pp. 897–917. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Credits

Current as ofApril 1, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review: Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine

Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine

E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine

Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine

Elizabeth T. Russo, MD – Internal Medicine

Ellen K. Roh, MD – Dermatology

Current as of: April 1, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine & Elizabeth T. Russo, MD – Internal Medicine & Ellen K. Roh, MD – Dermatology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.