Atopic Dermatitis (Eczema)

Topic Overview

What causes atopic dermatitis?

The cause of atopic dermatitis isn’t clear, but it affects your skin’s ability to hold moisture. Your skin becomes dry, itchy, and easily irritated.

Most people who have atopic dermatitis have a personal or family history of allergies, such as hay fever (allergic rhinitis) or asthma.

What are the symptoms?

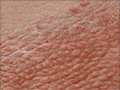

Atopic dermatitis starts with dry skin that is often very itchy. Scratching causes the dry skin to become red and irritated (inflamed). Infection often occurs. Tiny bumps that look like little blisters may appear and ooze fluid or crust over. These symptoms—dryness, itchiness, scratching, and inflammation—may come and go. Over time, a recurring rash can lead to tough and thickened skin.

Mild atopic dermatitis affects a small area of skin and may be itchy once in a while. Moderate and severe atopic dermatitis cover larger areas of skin and are itchy more often. And at times the itch may be intense.

People tend to get the rash on certain parts of the body, depending on their age. Common sites for babies include the scalp and face (especially on the cheeks), the front of the knees, and the back of the elbows. In children, common areas include the neck, wrists, legs, ankles, the creases of elbows or knees, and between the buttocks. In adults, the rash often appears in the creases of the elbows or knees and on the nape of the neck.

How is atopic dermatitis diagnosed?

A doctor can usually tell if you have atopic dermatitis by doing a physical exam and asking questions about your past health.

Your doctor may advise allergy testing to find the things that trigger the rash. Allergy tests can be done by an allergist (immunologist) or dermatologist.

How is it treated?

Atopic dermatitis is usually treated with medicines that are put on your skin (topical medicines). Gentle skin care, including using plenty of moisturizer, is also important.

Getting medical treatment early may keep your symptoms from getting worse.

If the topical medicines don’t help, your doctor may prescribe other treatments, such as pills, phototherapy, or injections.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

The cause of atopic dermatitis isn’t known. But most people who have it have a personal or family history of allergies, such as hay fever (allergic rhinitis). The skin inflammation that causes the atopic dermatitis rash is considered a type of allergic response.

Itching and rash can be triggered by many things, including:

- Allergens, such as dust mites, pollen, molds, or animal dander.

- Harsh soaps or detergents, rubbing the skin, and wearing wool.

- Workplace irritants, such as fumes and chemicals.

- Weather changes, especially dry and cold.

- Temperature changes, such as a suddenly higher temperature. This may bring on sweating, which can cause itching. Lying under blankets, entering a warm room, or going from a warm shower into colder air can all cause itching.

- Stress. Emotions such as frustration or embarrassment may lead to more itching and scratching.

- Certain foods, such as eggs, peanuts, milk, soy, or wheat products, if you are allergic to them. But experts don’t agree on whether foods can cause atopic dermatitis.

- Excessive washing. Repeated washing dries out the top layer of skin. This can lead to drier skin and more itching, especially in the winter months when humidity is low.

Symptoms

The main symptom of atopic dermatitis is itching. The itching can be severe and persistent, especially at night. Scratching the affected area of skin usually causes a rash. The rash is red and patchy and may be long-lasting (chronic) or come and go (recurring). The rash may:

- Develop fluid-filled sores that can ooze fluid or crust over. This can happen when the skin is rubbed or scratched or if a skin infection is present. This is known as an acute (sudden or of short duration), oozing rash.

- Be scaly and dry, red, and itchy. This is known as a subacute (longer duration) rash.

- Become tough and thick from constant scratching (lichenification).

How bad your symptoms are depends on how large an area of skin is affected, how much you scratch the rash, and whether the rash gets infected.

The areas most often affected are the face, scalp, neck, arms, and legs. The rash is also common in areas that bend, such as the back of the knees and inside of the elbows. Rashes in the groin or diaper area are rare. There may be age-related differences in the way the rash looks and behaves.

- Babies (2 months to 2 years): The rash is often crusted or oozes fluid. It’s most commonly seen during the winter months as dry, red patches on the cheeks.

- Children (2 years to 11 years): The rash is usually dry. But it may go through stages from an oozing rash to a red, dry rash that causes the skin to thicken. This thickened skin is called lichenification. It often occurs after the rash goes away.

For adolescents and adults, atopic dermatitis often improves as you get older.

What Happens

Atopic dermatitis is most common in babies and children. Most children outgrow it. But some teens and adults continue to have problems with it, though it’s usually not as bad as when they were children.

The condition may affect how children feel about themselves. If others can see the rash, a child may feel self-conscious and may need to be reassured.

Complications

Atopic dermatitis can cause problems with sleep. The itching caused by atopic dermatitis, especially during flares, can make it hard for children to fall asleep or to get good sleep.

Skin infections can happen more often in people with atopic dermatitis. The skin may become red and warm, and a fever may develop. Skin infections are treated with antibiotics.

One type of skin infection is eczema herpeticum. It happens when atopic dermatitis is infected with the herpes simplex virus. The rash will likely blister and may begin to bleed and crust. You may also have a high fever. This is a serious infection, so contact your doctor right away.

What Increases Your Risk

The major risk factor for atopic dermatitis is having a family history of the condition. You are also at risk if family members have asthma, allergic rhinitis, or other allergies.

When should you call your doctor?

Call your doctor if you or your child has atopic dermatitis and:

- Itching makes you or your child irritable.

- Itching is interfering with daily activities or with sleep.

- There are crusting or oozing sores, severe scratch marks, widespread rash, severe discoloration of the skin, or a fever that is accompanied by a rash.

- Painful cracks form on the hands or fingers.

- Atopic dermatitis on the hands interferes with daily school, work, or home activities.

- Signs of bacterial infection develop. These include:

- Increased pain, swelling, redness, tenderness, or heat.

- Red streaks extending from the area.

- A discharge of pus.

- A fever of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher with no other cause.

Who to see

For the diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis, consult with a:

If food or other allergies are suspected to be a factor in atopic dermatitis, you can see an allergist (immunologist) for specialized evaluation. For more information, see the topic Food Allergies.

Exams and Tests

Most cases of atopic dermatitis can be diagnosed from a medical history and a physical exam.

Allergy testing

Your doctor may recommend allergy testing to find out what might be causing your atopic dermatitis. Allergy testing is most helpful for people with atopic dermatitis who also have respiratory allergies or asthma.

Testing can also help find out if certain foods, such as eggs or nuts, are making the condition worse. Talk with your doctor about testing for allergies before making dietary changes.

If a specific allergen is thought to trigger your atopic dermatitis, you and your doctor will discuss how to remove it from your diet or environment while closely observing and recording your symptoms.

Treatment Overview

Treatment for atopic dermatitis depends on the type of rash you have. Most mild cases can be treated at home with moisturizers—especially skin barrier repair moisturizers—and gentle skin care. Most of the time, rash and itching can be controlled within 3 weeks.

- Moisturizers are a key part of treating atopic dermatitis. Use plenty of moisturizer (and use it several times a day) to reduce the itching, keep your rash from getting worse, and help your rash heal.

- Medicines that are put on the skin (topical medicines) include:

- Corticosteroids, which reduce itching and help the rash heal. They may be needed even with mild atopic dermatitis when the rash flares. Low-dose corticosteroids usually work well for this. For moderate or severe atopic dermatitis, stronger corticosteroid creams are used.

- Crisaborole (Eucrisa), an ointment used to treat mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. It can help the rash heal and works well to reduce itching and redness.

- Calcineurin inhibitors, which also reduce itching and help the rash heal. These medicines are used to treat moderate and severe atopic dermatitis.

Your doctor may talk to you about bleach baths and wet wraps. He or she will give you directions on how to use these treatments.

Getting medical treatment early may keep your symptoms from getting worse.

For rashes that don’t get better with medicines or moisturizers, treatment may include:

- High-strength topical corticosteroids. These may be used when the rash covers large areas of the body. They may also be used when complications occur, such as skin infections.

- Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light, with or without other medicine, at a clinic or doctor’s office. Options include phototherapy.

- Medicines such as cyclosporine, dupilumab, or interferon. These are sometimes used in adults if other treatment doesn’t work.

For itching, treatment may include antihistamines. Also, taking baths with colloidal oatmeal (such as Aveeno) or applying wet dressings to the rash for 30 minutes several times a day may help.

In severe cases, hospitalization may be needed. A short stay in the hospital can quickly control the condition.

What to think about

Counseling may be helpful for children and adults with atopic dermatitis. Talking with a counselor can help reduce stress and anxiety caused by atopic dermatitis and can help a person cope with the condition.

Prevention

If your baby is at risk for atopic dermatitis because you or other family members have it or other allergies, these steps may help prevent a rash or reduce its severity:

- If possible, breastfeed your baby for at least 6 months. Breastfeeding can boost your baby’s immune system.

- When you are ready to give your child solid foods, talk with your doctor. Ask if your child should avoid foods that often cause food allergies, such as eggs, peanuts, milk, soy, and wheat.

It may be possible to prevent peanut allergies by giving peanut protein to your baby when he or she starts solid foods. Ask your baby’s doctor about when and how to include peanut protein in your baby’s diet. If your baby has atopic dermatitis, you may help prevent peanut allergies by introducing peanut products early.

Home Treatment

Home treatment for atopic dermatitis includes taking care of your skin and avoiding things that irritate it.

Take care of your skin

- Take showers or baths in warm (not hot) water. Pat skin dry with a soft towel and put moisturizer on your skin right away.

- Avoid things that irritate a rash or make it worse, such as soaps that dry the skin, perfumes, and scratchy clothing or bedding.

- Avoid possible allergens that cause a rash or make a rash worse, such as dust mites, animal dander, and certain foods.

Control itching and scratching

- Keep your fingernails trimmed and filed smooth to help prevent damaging the skin when you scratch it.

- Use protective dressings to keep from rubbing the affected area. Put mittens or cotton socks on your baby’s hands to help prevent him or her from scratching the area.

Avoid sun and stress

- Exposure to natural sunlight can be helpful for atopic dermatitis, but it is important to avoid sunburn. Too much sun, sweating, and/or getting too hot also can irritate the skin. When you use a sunscreen, choose one for sensitive skin.

- Reduce stress to help your skin and keep rashes from getting worse. Try relaxation techniques, behavior modification, or biofeedback. Massage therapy is also helpful, especially in children.

Medications

Medicines for atopic dermatitis are used to help control itching and heal the rash. If you or your child has a very mild itch and rash, you may be able to control it without medicine by using home treatment and preventive measures. But if symptoms are getting worse despite home treatment, you will need to use medical treatment to prevent the itch-scratch-rash cycle from getting out of control.

Medicine choices

Topical medicines, such as creams or ointments, are applied directly to the skin.

- Topical corticosteroids are the most common and effective treatment for atopic dermatitis. Topical corticosteroids are only used for short periods of time since they can cause skin to shrink or change texture. This is especially true in areas where the skin is sensitive, like the face, neck, or groin area.

- Crisaborole (Eucrisa) is an ointment used to treat mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis. This medicine is a phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE-4) inhibitor that works well to heal the skin and help relieve symptoms such as itching and redness. It can cause burning or stinging when it is applied.

- Calcineurin inhibitors work well to treat atopic dermatitis. But they can weaken the body’s immune system, so they need to be used carefully. Pimecrolimus cream (Elidel) and tacrolimus ointment (Protopic) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating atopic dermatitis in people older than 2 years of age.

- These medicines are thought to be safe. But the FDA is concerned that there may be a link between these medicines and cancer as well as an increased risk for skin infections. The FDA requires that pimecrolimus and tacrolimus have labels that warn about these possible problems.

- Both of these medicines can cause some stinging or burning when they are put on the rash. This will be less noticeable as the rash heals. The burning feeling may be worse with tacrolimus ointment.

Both corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors are strong medicines, so be sure to follow carefully your doctor’s directions. They shouldn’t be used for long periods of time, so use them only as long as your doctor says. And any skin that has these medicines on it shouldn’t be covered with any material that keeps air from getting to your skin, unless your doctor tells you to.

Other medicines include:

- Antibiotic, antiviral, or antifungal medicines. These medicines are used if the rash gets infected. Skin that has been broken down by scratching and inflammation can become infected.

- Antihistamines.They are often used to treat atopic dermatitis itch. They can also help you sleep when severe night itching is a problem. But histamines aren’t always involved in atopic dermatitis itch, so these medicines may not help all people. Don’t give antihistamines to your child unless you’ve checked with the doctor first.

- Cyclosporine, dupilumab (Dupixent), or interferon. They are sometimes used in adults if other treatment doesn’t help.

Other Treatment

Other treatment for atopic dermatitis includes light therapy and complementary medicine.

Light therapy

Severe atopic dermatitis may be treated by exposing affected skin to ultraviolet (UV) light. There are two types of ultraviolet light, called ultraviolet A (UVA) and ultraviolet B (UVB). Phototherapy uses UVA, UVB, or a combination of UVA and UVB.

Too much sun exposure and light treatment (such as with UVA or UVB treatments) increases your risk of skin cancer.

Complementary medicine

Complementary medicine may be helpful for treating atopic dermatitis. Some small studies showed benefit from using probiotics. But there isn’t strong scientific evidence to show that they help.

Talk with your doctor about any complementary health practice that you would like to try or are already using. Your doctor can help you manage your health better if he or she knows about all of your health practices.

References

Citations

- Togias A, et al. (2017). Addendum guidelines for the prevention of peanut allergy in the United States: Report of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases-sponsored expert panel. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 139(1): 29-44. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010. Accessed August 23, 2017.

Other Works Consulted

- Berger TG (2012). Dermatologic disorders. In SJ McPhee, MA Papadakis, eds., 2012 Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment, 51st ed., pp. 93–163. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Bieber T (2008). Mechanisms of disease: Atopic dermatitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(14): 1483–1494.

- Greer FR, et al. (2008). Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: The role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas. Pediatrics, 121(1): 183–191. Also available online: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/121/1/183.full.

- Habif TP (2010). Atopic dermatitis. In Clinical Dermatology, A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy, 5th ed., pp. 154–180. Edinburgh: Mosby Elsevier.

- Habif TP, et al. (2011). Atopic dermatitis. In Skin Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment, 3rd ed., pp. 71–76. Edinburgh: Saunders.

- Krakowski AC, et al. (2008). Management of atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population. Pediatrics, 122(4): 812–824.

- Schmitt J, et al. (2011). Eczema, search date May 2009. Online version of BMJ Clinical Evidence: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

Current as of: April 1, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Martin J. Gabica MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Elizabeth T. Russo MD – Internal Medicine & Ellen K. Roh MD – Dermatology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.