Chronic Kidney Disease

Topic Overview

Is this topic for you?

This topic provides information about chronic kidney disease. If you are looking for information about sudden kidney failure, see the topic Acute Kidney Injury.

What is chronic kidney disease?

Having chronic kidney disease means that for some time your kidneys have not been working the way they should. Your kidneys have the important job of filtering your blood. They remove waste products and extra fluid and flush them from your body as urine. When your kidneys don’t work right, wastes build up in your blood and make you sick.

Chronic kidney disease may seem to have come on suddenly. But it has been happening bit by bit for many years as a result of damage to your kidneys.

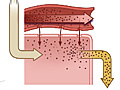

Each of your kidneys has about a million tiny filters, called nephrons. If nephrons are damaged, they stop working. For a while, healthy nephrons can take on the extra work. But if the damage continues, more and more nephrons shut down. After a certain point, the nephrons that are left cannot filter your blood well enough to keep you healthy.

One way to measure how well your kidneys are working is to figure out your glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The GFR is usually calculated using results from your blood creatinine (say “kree-AT-uh-neen”) test. Then the stage of kidney disease is figured out using the GFR. There are five stages of kidney disease, from kidney damage with normal GFR to kidney failure.

There are things you can do to slow or stop the damage to your kidneys. Taking medicines and making some lifestyle changes can help you manage your disease and feel better.

Chronic kidney disease is also called chronic renal failure or chronic renal insufficiency.

What causes chronic kidney disease?

Chronic kidney disease is caused by damage to the kidneys. The most common causes of this damage are:

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure over many years.

- High blood sugar over many years. This happens in uncontrolled type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

Other things that can lead to chronic kidney disease include:

- Kidney diseases and infections, such as polycystic kidney disease, pyelonephritis, and glomerulonephritis, or a kidney problem you were born with.

- A narrowed or blocked renal artery. A renal artery carries blood to the kidneys.

- Long-term use of medicines that can damage the kidneys. Examples include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as celecoxib and ibuprofen.

What are the symptoms?

You may start to have symptoms only a few months after your kidneys begin to fail. But most people don’t have symptoms early on. In fact, many don’t have symptoms for as long as 30 years or more. This is called the “silent” phase of the disease.

How well your kidneys work is called kidney function. As your kidney function gets worse, you may:

- Urinate less than normal.

- Have swelling and weight gain from fluid buildup in your tissues. This is called edema (say “ih-DEE-muh”).

- Feel very tired or sleepy.

- Not feel hungry, or you may lose weight without trying.

- Often feel sick to your stomach (nauseated) or vomit.

- Have trouble sleeping.

- Have headaches or trouble thinking clearly.

How is chronic kidney disease diagnosed?

Your doctor will do blood and urine tests to help find out how well your kidneys are working. These tests can show signs of kidney disease and anemia. (You can get anemia from having damaged kidneys.) You may have other tests to help rule out other problems that could cause your symptoms.

Your doctor will do tests that measure the amount of urea (BUN) and creatinine in your blood. These tests can help measure how well your kidneys are filtering your blood. As your kidney function gets worse, the amount of nitrogen (shown by the BUN test) and creatinine in your blood increases. The level of creatinine in your blood is used to find out the glomerular filtration rate (GFR). The GFR is used to show how much kidney function you still have. The GFR is also used to find out the stage of your kidney disease and to guide decisions about treatment.

Your doctor will ask questions about any past kidney problems. He or she will also ask whether you have a family history of kidney disease and what medicines you take, both prescription and over-the-counter drugs.

You may have a test that lets your doctor look at a picture of your kidneys, such as an ultrasound or CT scan. These tests can help your doctor measure the size of your kidneys, estimate blood flow to the kidneys, and see if urine flow is blocked. In some cases, your doctor may take a tiny sample of kidney tissue (biopsy) to help find out what caused your kidney disease.

How is it treated?

Chronic kidney disease is usually caused by another condition. So the first step is to treat the disease that is causing kidney damage.

Diabetes and high blood pressure cause most cases of chronic kidney disease. If you keep your blood pressure and blood sugar in a target range, you may be able to slow or stop the damage to your kidneys. Losing weight and getting more exercise can help. You may also need to take medicines.

Kidney disease is a complex problem. You will probably need to take a number of medicines and have many tests. To stay as healthy as possible, work closely with your doctor. Go to all your appointments. And take your medicines just the way your doctor says to.

Lifestyle changes are an important part of your treatment. Taking these steps can help slow down kidney disease and reduce your symptoms. These steps may also help with high blood pressure, diabetes, and other problems that make kidney disease worse.

- Follow a diet that is easy on your kidneys. A dietitian can help you make an eating plan with the right amounts of salt (sodium) and protein. You may also need to watch how much fluid you drink each day.

- Make exercise a routine part of your life. Work with your doctor to design an exercise program that is right for you.

- Do not smoke or use tobacco.

- Do not drink alcohol.

Always talk to your doctor before you take any new medicine, including over-the-counter remedies, prescription drugs, vitamins, or herbs. Some of these can hurt your kidneys.

What happens if kidney disease gets worse?

When kidney function falls below a certain point, it is called kidney failure. Kidney failure affects your whole body. It can cause serious heart, bone, and brain problems and make you feel very ill. Untreated kidney failure can be life-threatening.

When you have kidney failure, you will probably have two choices: start dialysis or get a new kidney (transplant). Both of these treatments have risks and benefits. Talk with your doctor to decide which would be best for you.

- Dialysis is a process that filters your blood when your kidneys no longer can. It is not a cure, but it can help you feel better and live longer.

- Kidney transplant may be the best choice if you are otherwise healthy. With a new kidney, you will feel much better and will be able to live a more normal life. But you may have to wait for a kidney that is a good match for your blood and tissue type. And you will have to take medicine for the rest of your life to keep your body from rejecting the new kidney.

Making treatment decisions when you are very ill is hard. It is normal to be worried and afraid. Discuss your concerns with your loved ones and your doctor. It may help to visit a dialysis center or transplant center and talk to others who have made these choices.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

The cause of chronic kidney disease isn’t always known. But any condition or disease that damages blood vessels or other structures in the kidneys can lead to kidney disease. The most common causes of chronic kidney disease are:

- Diabetes. High blood sugar levels caused by diabetes damage blood vessels in the kidneys. If the blood sugar level remains high over many years, this damage gradually reduces the function of the kidneys.

- High blood pressure (hypertension). Uncontrolled high blood pressure damages blood vessels, which can lead to damage in the kidneys. And blood pressure often rises with chronic kidney disease, so high blood pressure may further damage kidney function even when another medical condition initially caused the disease.

Other conditions that can damage the kidneys and cause chronic kidney disease include:

- Kidney diseases and infections, such as polycystic kidney disease, pyelonephritis, glomerulonephritis, or a kidney problem you were born with.

- Having a narrowed or blocked renal artery. A renal artery carries blood to the kidneys.

- Long-term use of medicines that can damage the kidneys. Examples include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as celecoxib and ibuprofen, and certain antibiotics.

Diabetes and high blood pressure are the most common causes of chronic kidney disease that leads to kidney failure. Diabetes or high blood pressure may also speed up the progression of chronic kidney disease in someone who already has the disease.

Symptoms

Many people who develop chronic kidney disease don’t have symptoms at first. This is known as the “silent” phase of the disease.

As your kidney function gets worse, you may:

- Urinate less than normal.

- Have swelling and weight gain from fluid buildup in your tissues (edema).

- Feel very tired.

- Lose your appetite or have an unexpected weight loss.

- Feel nauseated or vomit.

- Be either very sleepy or unable to sleep.

- Have headaches, or have trouble thinking clearly.

- Have a metallic taste in your mouth.

- Have severe itching.

What Happens

At first with chronic kidney disease, your kidneys are still able to regulate the balance of fluids, salts, and waste products in your body. But as kidney function decreases, you will start to have other problems, or complications. The worse your kidney function gets, the more complications you’ll have and the more severe they will be.

When kidney function falls below a certain point, it is called kidney failure. Kidney failure has harmful effects throughout your body. It can cause serious heart, bone, and brain problems and make you feel very ill.

After you have kidney failure, either you will need to have dialysis or you will need a new kidney. Both choices have risks and benefits.

Complications of chronic kidney disease

- Anemia. You may feel weak, have pale skin, and feel tired, because the kidneys can’t produce enough of the hormone (erythropoietin) needed to make new red blood cells.

- Electrolyte imbalance. When the kidneys can’t filter out certain chemicals, such as potassium, phosphate, and acids, you may have an irregular heartbeat, muscle weakness, and other problems.

- Uremic syndrome. You may be tired, have nausea and vomiting, not have an appetite, or not be able to sleep when substances build up in your blood. The substances can be poisonous (toxic) if they reach high levels. This syndrome can affect many parts of your body, including the intestines, nerves, and heart.

- Heart disease. Chronic kidney disease speeds up hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis) and increases the risk of stroke, heart attack, and heart failure. Heart disease is the most common cause of death in people with kidney failure.

- Bone disease (osteodystrophy). Abnormal levels of substances, such as calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D, can lead to bone disease.

- Fluid buildup (edema). As kidney function gets worse, fluids and salt build up in the body. Fluid buildup can lead to heart failure and pulmonary edema.

What Increases Your Risk

Some of the things that lead to chronic kidney disease are related to your age and your genetic makeup. You may be able to control other things that increase your risk, such as dietary habits and exercise.

Things you cannot control

The main risk factors for chronic kidney disease are:

- Age. The kidneys begin to get smaller as people get older.

- Race. African-Americans and Native Americans are more likely to get chronic kidney disease.

- Being male. Men have a higher risk for chronic kidney disease than women do.

- Family history. Family history is a factor in the development of both diabetes and high blood pressure, the major causes of chronic kidney disease. Polycystic kidney disease is one of several inherited diseases that cause kidney failure.

Things you may be able to control

You may be able to slow the progression of chronic kidney disease and prevent or delay kidney failure by controlling things that increase your risk of kidney damage, such as:

- High blood pressure, which gradually damages the tiny blood vessels in the kidneys.

- Diabetes. A persistently high blood sugar level can damage blood vessels in the kidneys. Over time, kidney damage can progress, and the kidneys may stop working altogether.

- Eating protein and fats. Eating a diet low in protein and fat may reduce your risk for kidney disease.

- Certain medicines. Avoid long-term use of medicines that can damage the kidneys, such as pain relievers called NSAIDs and certain antibiotics.

When should you call your doctor?

Call 911 or other emergency services if you have chronic kidney disease and you develop:

- A very slow heart rate (less than 50 beats a minute).

- A very rapid heart rate (more than 120 beats a minute).

- Chest pain or severe shortness of breath.

- Severe muscle weakness.

To check your heart rate, see the instructions for taking a pulse.

Call your doctor immediately if you:

- Have symptoms of uremic syndrome, such as increasing fatigue, nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, or inability to sleep.

- Vomit blood or have blood in your stools.

Call your doctor if you:

- Are feeling more tired or weak.

- Have swelling of the arms or feet.

- Bruise often or easily or have unusual bleeding.

- Are being treated with dialysis and you:

- Have belly pain while you are being treated with peritoneal dialysis.

- Have signs of infection at your catheter or dialysis access site, such as pus draining from the area.

- Have any other problem that your dialysis instruction manual or nurse’s instructions say you should call about.

If you have uncontrolled weight loss, discuss this with your doctor during your next visit.

Watchful waiting

A wait-and-see approach is not a good idea if you could have chronic kidney disease. See your doctor. If you have been diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, follow your treatment plan. And call your doctor if you notice any new symptoms.

Who to see

Health professionals who can diagnose and treat chronic kidney disease include:

- Family medicine physicians.

- Internists.

- Kidney specialists (nephrologists).

- Pediatricians.

- Nurse practitioners.

- Physician assistants (PA).

If you are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, you will likely be referred to a nephrologist for treatment.

You may also be referred to a:

- Surgeon, if you need a dialysis access site or if you are being considered for a kidney transplant.

- Dietitian, who can help you with meal planning and choosing foods that are best for people with this disease.

- Psychologist or social worker, who can help you and your family with emotional stress or financial issues.

Exams and Tests

Tests for chronic kidney disease are vital to help find out:

- Whether kidney disease happened suddenly or has been happening over a long time.

- What is causing the kidney damage.

- Which treatment is best to help slow kidney damage.

- How well treatment is working.

- When to begin dialysis or have a kidney transplant.

After you are diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, blood and urine tests can help you and your doctor monitor the disease.

Tests to check kidney function

When kidney function is decreased, substances such as urea, creatinine, and certain electrolytes begin to build up in the blood. The following tests measure levels of these substances to show how well your kidneys are working.

- A blood creatinine test helps to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) by measuring the level of creatinine in your blood. The doctor can use the GFR to regularly check how well the kidneys are working and to stage your kidney disease.

- A blood urea nitrogen (BUN) test measures how much nitrogen from the waste product urea is in your blood. BUN level rises when the kidneys aren’t working well enough to remove urea from the blood.

- A fasting blood glucose test is done to measure your blood sugar. High blood sugar levels damage blood vessels in the kidneys.

- Blood tests measure levels of waste products and electrolytes in your blood that should be removed by your kidneys.

- A blood test for parathyroid hormone (PTH) checks the level of PTH, which helps control calcium and phosphorus levels.

- Urinalysis (UA) and a urine test for microalbumin, or other urine tests, can measure protein in your urine. Normally there is little or no protein in urine.

Tests for anemia

If the kidneys don’t produce enough of the hormone erythropoietin needed to make red blood cells, anemia can develop. The following tests help monitor anemia:

- A complete blood count (CBC) measures the hematocrit and the hemoglobin level.

- A reticulocyte count shows how many red blood cells are being produced by the bone marrow.

- Iron studies show your level of iron, which is needed for erythropoietin to work the way it should.

- A serum ferritin test measures the protein that binds to iron in your body.

Other tests

Your doctor may use other tests to monitor kidney function or to find out whether another kidney disease or condition is contributing to reduced kidney function.

- An ultrasound of the kidney (renal ultrasound) helps estimate how long you may have had chronic kidney disease. It also checks whether urine flow from the kidneys is blocked. An ultrasound also may help find causes of kidney disease, such as obstruction or polycystic kidney disease.

- A duplex Doppler study or angiogram of the kidney may be done to check for problems caused by restricted blood flow (renal artery stenosis).

- A kidney biopsy may help find out the cause of chronic kidney disease. After a kidney transplant, a doctor may use this test if he or she suspects the organ is being rejected by your body.

Early screening for chronic kidney disease

Experts recommend screening tests for chronic kidney disease in high-risk groups, such as people with diabetes or high blood pressure. Kidney disease runs in families, so close family members may also want to have their kidney function tested. Being diagnosed with kidney disease before it has progressed gives you the best chance to control the disease.

To learn more about screening if you already have diabetes or high blood pressure, see:

Treatment Overview

The goal of treatment for chronic kidney disease is to prevent or slow further damage to your kidneys. Another condition such as diabetes or high blood pressure usually causes kidney disease, so it is important to identify and manage the condition that is causing your kidney disease. It is also important to prevent diseases and avoid situations that can cause kidney damage or make it worse.

Treatment to control kidney disease

Control the disease that’s causing the kidney damage

One of the most important parts of treatment is to control the disease that is causing kidney damage. You and your doctor will create a plan to aggressively treat and manage your condition to help slow any more damage to your kidneys.

If you have diabetes, it is important to control your blood sugar levels with diet, exercise, and medicines. A persistently high blood sugar level can damage the blood vessels in the kidneys. For more information about kidney disease caused by diabetes, see the topic Diabetic Nephropathy.

If you have high blood pressure, it is also important to keep your blood pressure in your target range. Your doctor will give you a goal for your blood pressure. To learn ways to help control your blood pressure, see the topic High Blood Pressure.

If other conditions or diseases are causing kidney damage, such as a blockage (obstruction) in the urinary tract or long-term use of medicines that can damage the kidneys, you and your doctor will work out a treatment plan.

Take medicines if prescribed

You may be prescribed a blood pressure medicine, such as an ACE inhibitor or an angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB). These medicines are used to reduce protein in the urine and help manage high blood pressure.

Have a healthy lifestyle

You can take steps at home to help control your kidney disease. For example:

- Follow a diet that is healthy for your kidneys. A dietitian can help you make an eating plan with the right amounts of salt (sodium), fluids, and protein.

- Make exercise a routine part of your life. Work with your doctor to make an exercise program that’s right for you.

- Don’t use substances that can harm your kidneys, such as alcohol, any kind of tobacco, or illegal drugs. Also, be sure that your doctor knows about all prescription medicines, over-the-counter medicines, and herbs that you are taking.

Go to all follow-up visits

Your doctor will use blood and urine tests to regularly check how well your kidneys are functioning and whether changes to your treatment plan are needed. These tests are critical to help monitor your disease. The tests include:

- Glomerular filtration rate (GFR), to estimate how well the kidneys filter your blood and to know which stage of kidney disease you’re in.

- Tests to measure the amount of protein in your urine, to find out whether your medicines need to be adjusted.

Treat any complications

As the disease gets worse, your symptoms—such as fatigue, nausea, and loss of appetite—may occur more often or become more severe. Work with your doctor to create a treatment plan to help control these symptoms.

If you develop anemia, you may need to take medicine called erythropoietin (EPO). It helps your body make new red blood cells and may help improve your appetite and general sense of well-being.

You may also need an iron supplement if you have an iron deficiency.

If you develop uremic syndrome (uremia), you will need to have wastes and fluids removed through dialysis or your kidney replaced through a kidney transplant.

Treatment for kidney failure

When your kidney function has fallen below a certain point, it is called kidney failure. Kidney failure has harmful effects throughout your body. It can cause serious heart, bone, and brain problems and can make you feel very ill.

After you have kidney failure, either you will need to have dialysis or you will need a new kidney. Both choices have risks and benefits.

Dialysis

Dialysis is a process that does the work of healthy kidneys by clearing wastes and extra fluid from the body and restoring the proper balance of chemicals (electrolytes) in the blood. You may use dialysis for many years, or it may be a short-term measure while you are waiting for a kidney transplant.

To learn more about dialysis, see Other Treatment.

Kidney transplant

Kidney transplant is often a better treatment option than dialysis for kidney failure, because it may allow you to live a fairly normal life. But there are some drawbacks. For example, you will probably need to have dialysis while you wait for a kidney.

To learn more about kidney transplants, see Surgery.

Making treatment decisions when you are very ill is difficult. It is normal to be fearful and worried about the risks involved. Discuss your concerns with your family and your doctor. It may be helpful to visit the dialysis center or transplant center and talk to others who have chosen these options.

Palliative care

Palliative care is a kind of care for people who have a serious illness. It’s different from care to cure your illness. Its goal is to improve your quality of life—not just in your body but also in your mind and spirit.

You can have palliative care along with treatment to cure your illness. You can also have it if treatment to cure your illness no longer seems like a good choice.

Palliative care providers will work to help control pain or side effects. They may help you decide what treatment you want or don’t want. And they can help your loved ones understand how to support you.

If you’re interested in palliative care, talk to your doctor.

For more information, see the topic Palliative Care.

End-of-life issues

Chronic kidney disease progresses to kidney failure when damage to the kidneys is so severe that dialysis or a kidney transplant is needed to control symptoms and prevent complications and death. Many people have successful kidney transplants or live for years using dialysis. But at this point you may wish to talk with your family and doctor about health care and other legal issues that arise near the end of life.

A time may come when your goals or the goals of your loved ones may change from treating or curing your disease to maintaining comfort and dignity. You may find it helpful and comforting to state your health care choices in writing (with an advance directive such as a living will) while you are still able to make and communicate these decisions. Think about your treatment options and which kind of treatment will be best for you. You may wish to write a durable power of attorney or choose a health care agent, usually a family member or loved one, to make and carry out decisions about your care if you become unable to speak for yourself. You also have the option to refuse or stop treatment. For more information, see the topic Care at the End of Life.

Prevention

Chronic kidney disease may sometimes be prevented by controlling the other diseases or factors that can contribute to kidney disease. People who have already developed kidney failure also need to focus on these things to prevent the complications of kidney failure.

- Work with your doctor to keep your blood pressure under control. Learn to check your blood pressure at home.

- If you have diabetes, keep your blood sugar within a target range. Talk with your doctor about how often to check your blood sugar.

- Stay at a healthy weight. This can help you prevent other diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease. For more information, see the topic Weight Management.

- Control your cholesterol levels. For more information, see the topic High Cholesterol.

- Don’t smoke or use other tobacco products. Smoking can lead to atherosclerosis, which reduces blood flow to the kidneys. For more information on how to quit, see the topic Quitting Smoking.

Home Treatment

There are many things you can do at home to slow the progression of chronic kidney disease.

Lifestyle changes

- Work with your doctor to keep your blood pressure under control. Learn to check your blood pressure at home.

- If you have diabetes, keep your blood sugar within a target range.

- Stay at a healthy weight. This can also reduce your risk for coronary artery disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and stroke. For more information, see the topic Weight Management.

- Follow the eating plan your dietitian created for you. Your eating plan will balance your need for calories with your need to limit certain foods, such as sodium, fluids, and protein.

- Make exercise a routine part of your life. Work with your doctor to design an exercise program that is right for you. Exercise may lower your risk for diabetes and high blood pressure.

- Don’t smoke or use other tobacco products. Smoking can lead to atherosclerosis, which reduces blood flow to the kidneys. For more information on how to quit, see the topic Quitting Smoking.

- Don’t drink alcohol or use illegal drugs.

What to avoid

- Avoid taking medicines that can harm your kidneys. Be sure that your doctor knows about all prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, and herbs you are taking.

- Avoid dehydration by promptly treating illnesses, such as diarrhea, vomiting, or fever, that cause it. Be especially careful when you exercise or during hot weather. For more information, see the topic Dehydration.

- Avoid products containing magnesium, such as antacids like Mylanta or Milk of Magnesia or laxatives like Citroma. These products increase your risk of having abnormally high levels of magnesium (hypermagnesemia), which may cause vomiting, diarrhea, or both.

- Avoid X-ray tests that require IV dye (contrast material), such as an angiogram, an intravenous pyelogram (IVP), and some CT scans. IV dye can cause more kidney damage. Make sure that your doctor knows about any tests that you are scheduled to have.

Medications

Although medicine cannot reverse chronic kidney disease, it is often used to help treat symptoms and complications and to slow further kidney damage.

Medicines to treat high blood pressure

Most people who have chronic kidney disease have problems with high blood pressure at some time during their disease. Medicines that lower blood pressure help to keep it in a target range and stop any more kidney damage.

Common blood pressure medicines include:

- ACE inhibitors.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs).

- Beta-blockers.

- Calcium channel blockers.

- Direct renin inhibitors.

- Diuretics.

- Vasodilators.

You may need to try several blood pressure medicines before you find the medicine that controls your blood pressure well without bothersome side effects. Most people need to take a combination of medicines to get the best results. Your doctor may order blood tests 3 to 5 days after you start or change your medicines. The tests help your doctor make sure that your medicines are working correctly.

Medicines to treat symptoms and complications of chronic kidney disease

Medicines may be used to treat symptoms and complications of chronic kidney disease. These medicines include:

- Erythropoietin (EPO) therapy and iron replacement therapy (iron pills or intravenous iron) for anemia.

- Medicines for electrolyte imbalances.

- Diuretics to treat fluid buildup caused by chronic kidney disease.

- ACE inhibitors and ARBs. These may be used if you have protein in your urine (proteinuria) or have heart failure. Regular blood tests are required to make sure that these medicines don’t raise potassium levels (hyperkalemia) or make kidney function worse.

Medicines used during dialysis

Both erythropoietin (EPO) therapy and iron replacement therapy may also be used during dialysis to treat anemia, which often develops in advanced chronic kidney disease.

- Erythropoietin (EPO) stimulates the production of new red blood cells and may decrease the need for blood transfusions. This therapy may also be started before dialysis is needed, when anemia is severe and causing symptoms.

- Iron therapy can help increase levels of iron in the body when EPO therapy alone is not effective.

- Vitamin D helps keep bones strong and healthy.

What to think about

Talk with your doctor about what types of immunizations you should have if you have chronic kidney disease, such as hepatitis B, flu (influenza), and pneumococcal vaccines.

Also, be sure to discuss medicine precautions. Make sure to tell your doctor about all prescription drugs, over-the-counter drugs, and herbs you are taking.

Surgery

Kidney transplant

If you have chronic kidney disease that progresses, you may have the option of a kidney transplant. Most experts agree that it is the best option for people with kidney failure. In general, people who have kidney transplants live longer than people treated with dialysis.

You will probably be considered a good candidate if you don’t have significant heart, lung, or liver disease or other diseases, such as cancer, which might decrease your life span.

There are some drawbacks. You may have to wait for a kidney to be donated. If so, you will need to have dialysis while you wait. Also, it may be hard to find a good match for your blood and tissue types. Sometimes, even when the match is good, the body rejects the new kidney.

After a kidney transplant, you will have to take medicines called immunosuppressants. These medicines, such as cyclosporine or tacrolimus, help prevent your body from rejecting your new kidney.

- It is very important to take your medicines exactly as prescribed. This will help keep your body from rejecting your new kidney.

- You will need to take medicines for the rest of your life.

- Because these medicines weaken the function of your immune system, you will have an increased risk for serious infections or cancer.

Even if you take your medicines, there is a chance that your body will reject your new kidney. If this happens, you will have to resume dialysis or have another kidney transplant.

The success of the transplant also depends on what kind of donor kidney you are receiving. The closer the donor kidney matches your genetic makeup, the better the chances that your body will not reject it.

For more general information about transplant, see the topic Organ Transplant.

What to think about

A kidney transplant doesn’t guarantee that you will live longer than you would have without a new kidney.

Other Treatment

Dialysis

Dialysis is a mechanical process that performs the work that healthy kidneys would do. It clears wastes and extra fluid from the body and restores the proper balance of chemicals (electrolytes) in the blood. When chronic kidney disease becomes so severe that your kidneys are no longer working properly, you may need dialysis. You may use dialysis to replace the work of the kidneys for many years. Or dialysis may be a short-term measure while you are waiting for a kidney transplant.

The two types of dialysis used to treat severe chronic kidney disease are hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis.

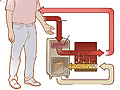

- Hemodialysis uses a man-made membrane called a dialyzer to clean your blood. You are connected to the dialyzer by tubes attached to your blood vessels. Before hemodialysis treatments can begin, a surgeon creates a site where blood can flow in and out of your body. This is called the dialysis access. Usually the doctor creates the access by joining an artery and a vein in the forearm or by using a small tube to connect an artery and a vein. An access may be created on a short-term basis by putting a small tube into a vein in your neck, upper chest, or groin.

- Peritoneal dialysis uses the lining of your belly, which is called the peritoneal membrane, to filter your blood. Before you can begin peritoneal dialysis, a surgeon needs to place a catheter in your belly to create the dialysis access.

What to think about

If you have severe chronic kidney disease but have not yet developed kidney failure, talk to your doctor about which type of dialysis would be best for you.

Learning about dialysis (predialysis education) is an important step in preparing for dialysis. Most dialysis clinics offer predialysis services to help you know about your choices.

References

Other Works Consulted

- Barry JM, Conlin MJ (2012). Renal transplantation. In AJ Wein et al., eds., Campbell-Walsh Urology, 10th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1226–1253. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Correa-Rotter R, et al. (2012). Peritoneal dialysis. In MW Taal et al., eds., Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney, 9th ed., vol. 2, pp. 2347–2377. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Fouque D, Mitch WE (2012). Dietary approaches to kidney disease. In MW Taal et al., eds., Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney, 9th ed., vol. 2, pp. 2170–2204. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Kendrick J, et al, (2015). Kidney disease and maternal and fetal outcomes in pregnancy. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 66(1): 55–59. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.11.019. Accessed August 26, 2015.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes CKD Work Group (2013). KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney International Supplements, 3(1): 1–150. Also available online: http://www.kdigo.org/clinical_practice_guidelines/ckd.php.

- Kopple JD (2014). Nutrition, diet, and the kidney. In AC Ross et al., eds., Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease, 11th ed., pp. 1330–1371. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins.

- National Kidney Foundation (2015). KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. American Journal of Kidney Diseases, 66(5): 884–930. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.07.015. Accessed January 8, 2016.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). 2008 Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (ODPHP Publication No. U0036). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Available online: http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/default.aspx.

- Wilkens KG, et al. (2012). Medical nutrition therapy for renal disorders. In LK Mahan et al., eds., Krause’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process, 13 ed., pp. 799–831. St Louis: Saunders.

- Yeun JY, et al. (2012). Hemodialysis. In MW Taal et al., eds., Brenner and Rector’s The Kidney, 9th ed., vol. 2, pp. 2294–2346. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Current as of: October 31, 2018

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Anne C. Poinier MD – Internal Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Tushar J. Vachharajani MD, FASN, FACP – Nephrology

Kidneys

Kidneys Taking a pulse (Heart Rate)

Taking a pulse (Heart Rate) Hemodialysis

Hemodialysis Peritoneal Dialysis

Peritoneal Dialysis Dialysis: Living Better With Dialysis

Dialysis: Living Better With Dialysis Dialysis: What Is It?

Dialysis: What Is It? Hemodialysis Access: When Is the Right Time?

Hemodialysis Access: When Is the Right Time?- <img alt=”” class=”HwMediaImage” data-resource-path=”media/thumbnails/abs5360.jpg” height=”107″ src=”https://content.healthwise.net/resources/12.2/en-us/media/thumbnails/abs5360