Depression

Topic Overview

Is this topic for you?

This topic covers depression in adults. For information on:

- Depression in young people, see the topic Depression in Children and Teens.

- Depression after childbirth, see the topic Postpartum Depression.

- Depression followed by times of high energy, see the topic Bipolar Disorder.

- Depression and suicide, see Depression and Suicide.

What is depression?

Depression is an illness that causes you to feel sad, lose interest in activities that you’ve always enjoyed, withdraw from others, and have little energy. It’s different from normal feelings of sadness, grief, or low energy. Depression can also cause people to feel hopeless about the future and even think about suicide.

Many people, and sometimes their families, feel embarrassed or ashamed about having depression. Don’t let these feelings stand in the way of getting treatment. Remember that depression is a common illness. It affects the young and old, men and women, all ethnic groups, and all professions.

If you think you may be depressed, tell your doctor. Treatment can help you enjoy life again. The sooner you get treatment, the sooner you will feel better.

What causes depression?

Depression is a disease. It’s not caused by personal weakness and is not a character flaw. When you have depression, there may be problems with activity levels in certain parts of your brain, or chemicals in your brain called neurotransmitters may be out of balance.

Most experts believe that a combination of family history (your genes) and stressful life events may cause depression. Life events can include a death in the family or having a long-term health problem.

Just because you have a family member with depression or have stressful life events doesn’t mean you’ll get depression.

You also may get depressed even if there is no reason you can think of.

What are the symptoms?

The symptoms of depression may be hard to notice at first. They vary among people, and you may confuse them with just feeling “off” or with another health problem.

The two most common symptoms of depression are:

- Feeling sad or hopeless nearly every day for at least 2 weeks.

- Losing interest in or not getting pleasure from most daily activities that you used to enjoy, and feeling this way nearly every day for at least 2 weeks.

A serious symptom of depression is thinking about death or suicide. If you or someone you care about talks about this or about feeling hopeless, get help right away.

If you think you may have depression, take a short quiz to check your symptoms:

How is it treated?

Depression can be treated in various ways. Counseling, psychotherapy, and antidepressant medicines can all be used. Lifestyle changes, such as getting more exercise, also may help.

Work with your health care team to find the best treatment for you. It may take a few tries, and it can take several weeks for the medicine and therapy to start working. Try to be patient and keep following your treatment plan.

Depression can return (relapse). How likely you are to get depression again increases each time you have a bout of depression. Taking your medicines and continuing some types of therapy after you feel better can help keep that from happening. Some people need to take medicine for the rest of their lives. This doesn’t stop them from living full and happy lives.

What can you do if a loved one has depression?

If someone you care for is depressed, the best thing you can do is help the person get or stay in treatment. Learn about the disease. Talk to the person, and gently encourage him or her to do things and see people. Don’t get upset with the person. The behavior you see is the disease, not the person.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Depression is a disease. It isn’t caused by personal weakness, and it isn’t a character flaw. When you have depression, there may be problems with activity levels in certain parts of your brain, or chemicals in your brain called neurotransmitters may be out of balance.

Most experts believe that a combination of family history (your genes) and stressful life events may cause depression.

- Genes: Your chance of having a bout of depression is greater if other family members have had depression. You may have inherited a trait that makes you more likely to get depressed. If this is true for you, a stressful life event is more likely to trigger depression.

- Thinking styles: How you think can affect how you feel. You may be more likely to become depressed if you tend to:

- Think in extremes. For example, thinking, “If I can’t do something perfectly, I might as well quit.”

- Concentrate on your weaknesses and ignore your strengths.

- Take things personally that have little or nothing to do with you. For example, if your boss has a stern look on his or her face, you think “My boss must be mad at me, because he (or she) is not smiling.”

- Pay attention to the dark side of things, or exaggerate the chances of a bad outcome. For example, thinking “If I make a mistake, I will be fired from my job.”

- Life events: Stressful life events can trigger depression. For example, you could become depressed if you have:

- Lost a loved one.

- Had a baby (depression after childbirth).

- Recently divorced.

- Been diagnosed with a long-term disease such as diabetes or heart disease.

Sometimes even happy life events, such as a marriage or promotion, can trigger depression because of the stress that comes with change.

Just because you have a family member with depression or have stressful life events doesn’t mean you’ll get depression. You also may get depression without going through a stressful event.

Other causes

Most health problems do not cause depression. But some such as anemia or an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism) can make you tired, which may seem like depression. Treating the health problem usually cures the fatigue. And sometimes health problems can make depression worse.

Certain medicines, such as steroids or opioids, can cause depression. If you stop using the medicine, the depression may go away.

Symptoms

The symptoms of depression may be hard to notice at first. They can be different from person to person. You may confuse them with just feeling “off” or “down.” You also may confuse the symptoms with another health problem.

The two most common symptoms of depression are:

- Feeling sad, empty, or tearful nearly every day.

- Losing interest in or not getting pleasure from most daily activities that you used to enjoy, and feeling this way nearly every day.

If you have felt this way for at least two weeks, it is possible you are experiencing depression.

A serious symptom of depression is thinking about death and suicide. If you or someone you care about talks about suicide or feeling hopeless, get help right away.

You also may:

- Lose or gain weight. You may also feel like eating more or less than usual almost every day.

- Sleep too much or not enough almost every day.

- Feel restless and not be able to sit still, or you may sit quietly and feel that moving takes great effort. Others can easily see this behavior.

- Feel tired or as if you have no energy almost every day.

- Feel unworthy or guilty nearly every day. You may have low self-esteem and worry that people don’t like you.

- Find it hard to focus, remember things, or make decisions nearly every day. You may feel anxious or worried about things.

It’s possible to have periods of both energy and elation (mania) and depression. This may be bipolar disorder. If this happens to you, tell your doctor. The treatments for depression and bipolar disorder are different.

Symptoms can vary

Symptoms can be mild, moderate, or severe:

- In mild depression, you have few symptoms.

- In moderate depression, you have more symptoms, and they are beginning to change your life.

- In severe depression, the symptoms change your life and affect your job or career and your relationships.

Depression can affect your physical health. You may have headaches or other aches and pains or have digestive problems such as constipation or diarrhea. You may have trouble having sex or may lose interest in it. If you notice any of these changes, talk to your doctor. He or she may be able to help.

One Woman’s Story: “I woke up every day with suicide on my mind, and I went to bed with suicide on my mind.” —Martha |

Symptoms in older adults

Depression can make older adults confused or forgetful or cause them to stop seeing friends and doing things. It can be confused with problems like dementia.

Are you depressed?

If you think you may have depression, take a short quiz to check your symptoms:

Other types of depression

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) may happen in women when premenstrual mood changes are making daily life hard or are harming relationships. To learn more, see the topic Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS).

- Postpartum depression may happen when women feel very sad after having a baby. To learn more, see the topic Postpartum Depression.

What Happens

Depression is different for everyone.

For some people, a bout of depression begins with symptoms of anxiety (such as worrying a lot), sadness, or lack of energy. This may go on for days or months before the person or others think that depression could be the problem.

And other people may feel depressed suddenly. This may happen after a big change in life, such as the loss of a loved one or a serious accident.

How long does depression last?

If you don’t get treated, depression may last from months to a year or longer.

A small number of people feel depressed for most of their lives and always need treatment.

Depression can return, which is called a relapse. At least half of the people who have depression once get it again.footnote 1 How likely you are to get depression again increases each time you have a bout of depression. You can make having another bout of depression less likely by following your treatment plan and using your medicines.

Depression and other health concerns

Depression is linked with many health concerns. These include other diseases, drug or alcohol use, and pregnancy. If you have depression and another health concern, you need to deal with both of them.

Read about:

- Depression, anxiety, and other health problems.

- Depression and problems with drugs or alcohol.

- Depression and aging.

- Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Depression and suicide.

- Depression during pregnancy and after having a baby (postpartum depression).

What Increases Your Risk?

Experts don’t know why some people get depression and others don’t. But certain things make you likely to get depression. These are called risk factors.

Important risk factors for depression include:

- Having a father, mother, brother, or sister who has had depression.

- Having had depression before.

- Having post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- One-time stressful events, such as the death of a loved one, losing your independence or your job, or having a serious accident.

Other risk factors include:

- Long-term (chronic) stressful situations, such as living in poverty, having marriage or family problems, or helping someone who has a long-term medical problem.

- Physical or sexual abuse in childhood or in a relationship, such as domestic abuse or violence.

- Getting older.

Medical risk factors

Medical problems also may cause depression or make it worse. These problems include:

- Having substance use disorder.

- Having a long-term (chronic) health problem, such as coronary artery disease, diabetes, cancer, or chronic pain. Read more about depression and chronic illness.

- Having a mental health problem or behavior disorder, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), dementia, anxiety disorder, or an eating disorder.

- Having had a recent serious illness or surgery.

- Having a health problem such as anemia or an underactive thyroid gland (hypothyroidism). Treating the health problem usually cures the depression.

- Using certain medicines, such as steroids or opioids. If you stop using the medicine, the depression will probably go away.

Other risk factors for women

Women have more risk factors. These include:

- Menopause.

- Pregnancy or recent childbirth. For more information on depression after childbirth, see the topic Postpartum Depression.

- Use of birth control that contain hormones.

- A history of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (severe premenstrual syndrome).

When to Call a Doctor

Call 911, the national suicide hotline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255), or other emergency services right away if:

- You or someone you know is thinking seriously about or has attempted suicide. Serious signs include these thoughts:

- You have decided on how to kill yourself, such as with a weapon or medicines.

- You have set a time and place to do it.

- You think there is no other way to solve the problem or end the pain.

- You feel you cannot stop from hurting yourself or someone else.

Call a doctor right away if:

- You hear voices.

- You have been thinking about death or suicide a lot, but you do not have a plan to harm yourself.

- You are worried that your feelings of depression or thoughts of suicide are not going away.

Seek care soon if:

- You have symptoms of depression, such as:

- Feeling sad or hopeless.

- Not enjoying anything.

- Having trouble with sleep.

- Feeling guilty or worthless.

- Feeling anxious or worried.

- You have been treated for depression for more than 3 weeks, but you are not getting better.

If you have not been diagnosed with depression but you think you may be depressed, use the Feeling Depressed topic to check your symptoms.

Who to see

Your family doctor can help you with depression. If treatment by your doctor doesn’t help you, the next step is to see a mental health professional.

No matter who you see, it is important that this person has experience treating people who have depression and is trained in proven therapies. It is also important that you establish a good long-term relationship. If you don’t feel comfortable with one doctor or therapist, try another one.

Health professionals who can diagnose depression and prescribe medicine include:

- Family medicine physicians.

- Internists.

- Psychiatrists.

- Physician assistants.

- Nurse practitioners.

- Obstetricians or gynecologists.

Treatment such as professional counseling or therapy can be provided by:

- Psychiatrists (who can also diagnose and prescribe medicines).

- Psychologists.

Other health professionals who also may be trained in treating depression include:

Exams and Tests

Depression may be diagnosed when you talk to your doctor about feeling sad or when your doctor asks you questions and discovers that you are feeling sad. You may be seeing your doctor because you feel sad or because you have another health problem or concern.

If your doctor thinks you are depressed, he or she will ask you questions about your health and feelings. This is called a mental health assessment. Your doctor also may:

- Do a physical exam.

- Do tests to make certain your depression isn’t caused by a disease such as an underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) or anemia. Depending on your history and risk factors, your doctor may order other tests.

- Ask you about suicide.

- Ask you about bipolar disorder if you sometimes feel energetic and elated. To learn more, see the topic Bipolar Disorder.

- Ask you about seasonal affective disorder if you only have depression at certain times of the year. To learn more, see the topic Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD).

- Ask you if you have recently lost a loved one.

- Ask about your drug and alcohol use.

Early detection

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that all people, starting at age 12, be screened for depression. Screening for depression helps find depression early. And early treatment may help you get better faster.

Treatment Overview

Treatment for depression includes counseling, medicines, and lifestyle changes. Your treatment will depend on you and your symptoms. You and your health care team will work together to find the best treatment for you.

- If you are using medicine, your doctor may have you try different medicines or a combination of medicines.

- You may need to go to the hospital if you show warning signs of suicide, such as having thoughts about harming yourself or another person, not being able to tell the difference between what is real and what is not (psychosis), or using a lot of alcohol or drugs.

If you don’t get treated, depression may last from months to a year or longer. A small number of people feel depressed for most of their lives and always need treatment.

If you need help deciding whether to talk to your doctor about depression, see some common reasons people don’t get help and how to overcome them.

You can help yourself by getting support from family and friends, staying active, eating a balanced diet, avoiding alcohol, and getting enough sleep. See Living with Depression.

Other treatments

Other treatments for depression include:

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

- Complementary therapies are sometimes used for depression. Always tell your doctor if you are using any of them.

One Man’s Story: “…[T]his was the first time I was willing to do anything to recover. It’s changed my whole life.” —Stan |

Prevention

Little is known about how to prevent depression, but getting exercise and avoiding alcohol and drugs may help. Exercise may also help prevent depression from coming back (relapse) and may improve symptoms of mild depression.

You also may be able to prevent depression by avoiding alcohol and drugs. Alcohol and drugs can contribute to depression. And using them can be a sign that you have depression.

Preventing depression from coming back

You may be able to prevent a relapse or keep your symptoms from getting worse if you:

- Take your medicine as prescribed. Depression often returns if you stop taking your medicine or don’t take it as your doctor advises.

- Continue to take your medicine after your symptoms improve. Taking your medicine for at least 6 months after you feel better can help keep you from getting depressed again. If this isn’t the first time you have been depressed, your doctor may want you to take medicine even longer. You may benefit from long-term treatment with antidepressants.

- Continue cognitive-behavioral therapy after your symptoms improve. Research shows that people who were treated with this type of therapy had less chance of relapse than those who were treated only with antidepressants.footnote 2

- Eat a balanced diet.

- Get regular exercise.

- Get treatment right away if you notice that symptoms of depression are coming back or getting worse.

- Have healthy sleep patterns.

- Avoid drugs and alcohol.

Therapy

Counseling and psychotherapy are important parts of treatment for depression. You will work with a mental health professional such as a psychologist, licensed professional counselor, clinical social worker, or psychiatrist. Together you will develop an action plan to treat your depression.

When you hear “counseling” or “therapy,” you may think of lying on a couch and talking about your childhood. But most of these treatments don’t look for hidden memories. They deal with how you think about things and how you act each day.

The first step is finding a therapist you trust and feel comfortable with. The therapist also should have experience treating people who have depression and should be trained in proven therapies. These therapies include:footnote 3

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which teaches you how to change the ways you think and behave. This can help you stop thinking bad thoughts about yourself and your life. You can take part in CBT with a therapist or in a group setting.

- Interpersonal therapy, which looks at your social and personal relationships and related problems.

Other therapies that have helped people with depression are:footnote 4footnote 5

- Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). In ACT, you work with a therapist to learn to accept your negative feelings but not let them run your life. You learn to make choices and act based on your personal values, not negative feelings.

- Mindfulness-based therapies, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction or Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy. These treatments help you to focus your attention on what is happening at the moment without trying to change it. These strategies teach you to let go of past regrets and not worry about the future. For people who have had more than one episode of depression, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy may help reduce the risk of relapse.

Other treatments you may have heard of include problem-solving therapy, which looks at your current problems and helps you solve them, and family therapy, which brings you and your family together to discuss your relationships and depression. Experts don’t know how well these therapies work for depression.footnote 3 Problem-solving therapy may be especially helpful for older adults.footnote 6

One Woman’s Story: “I walked into the therapist’s office crying, mute. I felt as if no one heard me.” —Debbie |

How long will you need therapy?

How long your treatment lasts depends on how severe your depression is and how well you respond to treatment. Short-term counseling or therapy usually lasts from 10 to 20 weeks, and you usually see your mental health professional once a week. But you may need to meet with your health professional more often or for a longer time.

Medicines

Antidepressant medicines may improve or completely relieve the symptoms of depression. Whether you need to take medicine depends on your symptoms. You and your doctor can decide if you need medicine and which medicine is right for you.

Antidepressant medicines work in different ways. No antidepressant works better than another, but different ones work better or worse for different people. The side effects of antidepressant medicines are different and may lead you to choose one instead of another.

You may have to try different medicines or take more than one to help your symptoms. Most people find a medicine that works within a few tries. Other people take longer to find the right one and may need to take the antidepressant and another type of medicine, such as an antiseizure, mood stabilizer, antipsychotic, or antianxiety medicine.

Together you and your doctor will decide if you need medicine, what things you’ll need to think about if you need medicine, and which medicine is right for you.

Medicine choices

Antidepressant medicines include:

- Bupropion (Wellbutrin, Wellbutrin SR).

- Citalopram (Celexa).

- Fluoxetine (Prozac).

- Venlafaxine (Effexor, Effexor XR).

Side effects and safety

Antidepressant medicines have side effects. You may notice the side effects before you notice that the medicine is helping you. Side effects vary depending on the medicine you take.

People who are taking medicines for other health problems need to know about medicine interactions. Talk with your doctor about the best way to track whether a combination of medicines is harming you. People who are taking a lot of medicines also are more likely to have harmful side effects.

One Woman’s Story “It took about a year for me to not feel depressed at all.” —Sherri |

How long will you need medicines?

If you take antidepressants, you should take them for at least 6 months after you begin to feel better. This can help prevent you from feeling depressed again (relapse). If this isn’t the first time you have been depressed, your doctor may want you to take these medicines even longer.

You may start to feel better within 1 to 3 weeks after starting your antidepressant medicine. But it can take as many as 6 to 8 weeks to see a great deal of improvement. If you have questions or concerns about your medicines, or if you don’t notice that you feel better by 3 weeks, talk to your doctor.

Some people need to remain on medicine for several months to years. Others will need medicine long-term. This is more likely if you have had several bouts of depression that seriously affected your home life, work life, or both.

Don’t quit taking your medicines without talking to your doctor. If you quit suddenly, it can cause your depression to return and it can cause dizziness, anxiety, fatigue, and headache. If you and your doctor decide you can quit using medicine, gradually reduce the dose over several weeks.

Living With Depression

When you’re going through depression, you can’t just shake it off. You might have a couple of good days followed by a bad day or a string of bad days. And you don’t know how long it will last. Depression isn’t like the flu or a sprained ankle, where your doctor can tell you about how long it will take to get better.

When you’re getting better, many experts call it recovery. Recovery is finding your path to the life you care about.

During your recovery, be patient and kind to yourself. Remember that depression isn’t your fault and isn’t something you can overcome with willpower alone. You need treatment for depression, just like for any other illness.

Continuing your treatment, helping yourself, getting support, and having a healthy lifestyle are all part of your recovery. Your symptoms will fade as your treatment starts to work. Don’t give up. Focus your energy on getting better. Your mood will improve. It just takes some time.

Your self-care

You can take many steps to help yourself when you feel depressed or are waiting for your medicine to work. These steps also help prevent depression from coming back.

- Be realistic in what you expect and what you can do. Set goals you can meet. If you have a big task to do, break it up into smaller steps you can handle. Don’t take on more than you can handle.

- Don’t blame yourself or others for your depression.

- Think about putting off big decisions until your depression has lifted. Wait a bit on making decisions about marriage, divorce, or jobs. Talk it over with friends and loved ones who can help you look at the whole picture.

- Get support from others. Your family can help you get the right treatment and deal with your symptoms. Social support and support groups give you the chance to talk with people who are going through the same things you are.

- Tell people you trust about depression. It is usually better than being alone and keeping it a secret.

- Build your self-esteem, and try to keep a positive attitude.

- Try to be part of religious, social, holiday, or other activities.

- If you have any other health problems, like diabetes, heart disease, or high blood pressure, continue with your treatment for them. Tell your doctor about all of the medicines you take, with or without a prescription.

You also can help yourself by thinking about what is good in your life. You can:

- Help others who are not as well off as you are.

- Thank people for the small and big things they do for you.

- Be thankful for big things like having a home, family, and friends.

- Be thankful for little things like making people laugh, enjoying a piece of music, or finding warm gloves for the winter.

One Woman’s Story: “If you keep your thoughts in, they will never be quiet. It helps my depression to express them.” —Cheryl |

Remember the basics

- Get regular exercise. People who are fit usually have less anxiety, depression, and stress than people who aren’t fit. Even something as easy as walking can help you feel better.

- Eat a balanced diet. This helps your body deal with tension and stress.

- Get enough sleep. A good night’s sleep can help mood and stress levels. Avoid sleeping pills unless your doctor prescribes them.

- Deal with stress. Too much stress can help trigger depression.

- Avoid drinking alcohol or using illegal drugs or medicines that have not been prescribed to you. Having substance use disorder makes treating depression harder. Both problems need to be treated.

- Prevent depression from coming back. Take your medicine as your doctor advises. Depression often returns if you stop taking your medicine or don’t take it as your doctor advises.

Other Treatment

Brain stimulation

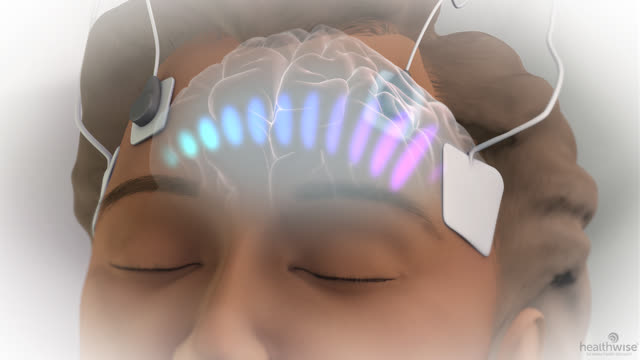

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be used to treat severe depression or depression that doesn’t get better with medicine and counseling or therapy.

Other types of brain stimulation have not been well studied and may be expensive. They usually are considered only if other treatment doesn’t work. They include:

- Deep brain stimulation. A device that uses electricity to stimulate the brain is put in your head. It is used for Parkinson’s disease but has not been well studied for depression.

- Vagus nerve stimulation. A generator the size of a pocket watch is placed in your chest. Wires go up from the generator to the vagus nerve in your neck. The generator sends tiny electric shocks through the vagus nerve to the brain.

- Transcranial magnetic stimulation. An electromagnet is placed on your head. It sends magnetic pulses that stimulate your brain.

Complementary therapies

Complementary therapies are sometimes used for depression. Always tell your doctor if you are using any of them. These therapies include:

- Massage therapy, yoga, and other relaxation exercises.

- Fish oil containing omega-3 fatty acids.

- SAM-e (S-adenosylmethionine).

For Family and Friends

If someone you care about is depressed, you may feel helpless. Maybe you’re watching a once-active or happy person slide into inactivity, or you’re seeing a good friend lose interest in favorite activities. The change in your loved one’s or friend’s behavior may be so big that you feel you no longer know him or her.

Here are some things you can do to help:

- Help the person get treatment or stay in treatment. This is the best thing you can do.

- Support and encourage the person.

- Learn about depression. Know the facts and myths about it.

- Be aware of your own and other people’s negative attitudes (stigma) toward depression. Do what you can to fight stigma and teach people about depression.

- Be aware of other health problems the person may have, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Help the person have good health habits. See “Remember the basics” in Living With Depression.

- Find your own support. Others can give you emotional and practical support when you are helping a loved one who has depression.

One Woman’s Story: “Having a friend or loved one to help you can really help.” —Susan |

Related Information

- Feeling Depressed

- Postpartum Depression

- Bipolar Disorder

- Reducing Medication Costs

- Alcohol Use Disorder

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

- Depression in Children and Teens

- Complementary Medicine

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder

- Substance Use Disorder

- Dealing With Medicine Side Effects and Interactions

- Anorexia Nervosa

- Panic Attacks and Panic Disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

- Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS)

- Aromatherapy (Essential Oils Therapy)

References

Citations

- Young JE, et al. (2008) Cognitive therapy for depression. In DH Barlow, ed., Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, 4th ed., pp. 250–305. New York: Guilford Press.

- Hollon SD, et al. (2005). Prevention of relapse following cognitive therapy vs. medications in moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4): 417–422.

- Butler R, et al. (2007). Depression in adults: Psychological treatments and care pathways, search date April 2006. BMJ Clinical Evidence. Available online: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Khoury B, et al. (2013). Mindfulness-based therapy: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6): 763–771.

- Powers MB, et al. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(2): 73–80.

- Arean P, et al. (2008). Effectiveness of problem-solving therapy for older, primary care patients with depression: Results from the IMPACT project. Gerontologist, 48(3): 311–323.

Other Works Consulted

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2008, reaffirmed 2009). Use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 92. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 111(4): 1001–1020.

- American Psychiatric Association (2010). Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder, 3rd ed. Available online: http://psychiatryonline.org/guidelines.aspx.

- Canadian Psychiatric Association and the CANMAT Depression Work Group (2001). Clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of depressive disorders. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(Suppl 1): S13–S89.

- Matorin AA, Ruiz P (2009). Clinical manifestations of psychiatric disorders. In BJ Sadock et al., eds., Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, 9th ed., vol. 1, pp. 1071–1107. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Murray MT, Bongiorno PB. (2006). Affective disorders. In JE Pizzorno Jr, MT Murray, eds. Textbook of Natural Medicine, 3rd ed., vol. 2, pp. 1427–1448. St. Louis: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

- Qaseem A, et al. (2008). Using second-generation antidepressants to treat depressive disorders: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 149(10): 725–733. Also available online: http://annals.org/article.aspx?articleid=743690.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA (2007). Depression and bipolar disorder. In Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry, 10th ed., pp. 527-562. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Safety of SSRI in pregnancy (2008). Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics, 50(1299): 89–90.

Current as of: May 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Lisa S. Weinstock MD – Psychiatry

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.