Ear Infections

Topic Overview

Is this topic for you?

This topic covers infections of the middle ear, commonly called ear infections. For information on outer ear infections, see the topic Ear Canal Problems (Swimmer’s Ear).For information on inner ear infections, see the topic Labyrinthitis.

What is a middle ear infection?

The middle ear is the small part of your ear behind your eardrum. It can get infected when germs from the nose and throat are trapped there.

What causes a middle ear infection?

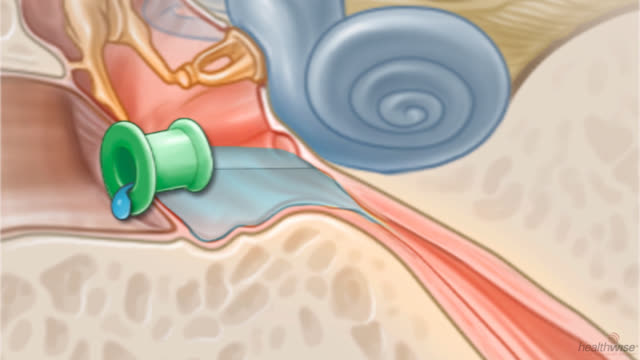

A small tube connects your ear to your throat. These two tubes are called eustachian tubes (say “yoo-STAY-shee-un”). A cold can cause this tube to swell. When the tube swells enough to become blocked, it can trap fluid inside your ear. This makes it a perfect place for germs to grow and cause an infection.

Ear infections happen mostly to young children, because their tubes are smaller and get blocked more easily.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptom is an earache. It can be mild, or it can hurt a lot. Babies and young children may be fussy. They may pull at their ears and cry. They may have trouble sleeping. They may also have a fever.

You may see thick, yellow fluid coming from their ears. This happens when the infection has caused the eardrum to burst and the fluid flows out. This isn’t serious and usually makes the pain go away. The eardrum usually heals on its own.

When fluid builds up but doesn’t get infected, children often say that their ears just feel plugged. They may have trouble hearing, but their hearing usually returns to normal after the fluid is gone. It may take weeks for the fluid to drain away.

How is a middle ear infection diagnosed?

Your doctor will talk to you about your child’s symptoms. Then he or she will look into your child’s ears. A special tool with a light lets the doctor see if the eardrum is red and if there is fluid behind it. This exam is rarely uncomfortable. It bothers some children more than others.

How is it treated?

Most ear infections go away on their own, although antibiotics are recommended for children under the age of 6 months and for children at high risk for complications. You can treat your child at home with an over-the-counter pain reliever like acetaminophen (such as Tylenol), a warm washcloth on the ear, and rest. Do not give aspirin to anyone younger than 20. Your doctor may give you eardrops that can help your child’s pain. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

Your doctor can give your child antibiotics, but ear infections often get better without them. Talk about this with your doctor. Whether you use them will depend on how old your child is and how bad the infection is.

Minor surgery to put tubes in the ears may help if your child has hearing problems or repeat infections.

Sometimes after an infection, a child cannot hear well for a while. Call your doctor if this lasts for 3 to 4 months. Children need to be able to hear in order to learn how to talk.

Can ear infections be prevented?

There are many ways to help prevent ear infections.

- Do not smoke. Ear infections happen more often to children who are around cigarette smoke. Even the fumes from tobacco smoke on your hair and clothes can affect them.

- Encourage hand-washing.

- Breastfeed your baby.

- Have your child immunized.

- Make sure your child doesn’t go to sleep while sucking on a bottle.

- Try to limit the use of group child care.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Middle ear infections are caused by bacteria and viruses.

Swelling from an upper respiratory infection or allergy can block the eustachian tubes, which connect the middle ears to the throat. So air can’t reach the middle ear. This creates a vacuum and suction, which pulls fluid and germs from the nose and throat into the middle ear. The swollen tube prevents this fluid from draining. The fluid is a perfect breeding ground for bacteria or viruses to grow into an ear infection.

- Bacterial infections. Bacteria cause many ear infections. The most common types are Streptococcus pneumoniae (also called pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis.

- Viral infections. Viruses can also lead to ear infections. The respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and flu (influenza) virus are the types most frequently found.

Inflammation and fluid buildup can occur without infection and cause a feeling of stuffiness in the ears. This is known as otitis media with effusion.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a middle ear infection (acute otitis media) often start 2 to 7 days after the start of a cold or other upper respiratory infection. Symptoms of an ear infection may include:

- Ear pain (mild to severe). Babies often pull or tug at their ears when they have an earache.

- Fever.

- Drainage from the ear that is thick and yellow or bloody. This means the eardrum has probably burst (ruptured). The hole in the eardrum often heals by itself in a few weeks.

- Loss of appetite, vomiting, and grumpy behavior.

- Trouble sleeping.

Symptoms of fluid buildup may include:

- Popping, ringing, or a feeling of fullness or pressure in the ear. Children often have trouble describing this feeling. They may rub their ears trying to relieve pressure.

- Trouble hearing. Children who have problems hearing may seem dreamy or inattentive, or they may appear grumpy or cranky.

- Balance problems and dizziness.

Some children don’t have any symptoms.

What Happens

Middle ear infection

Middle ear infections usually occur along with an upper respiratory infection (URI), such as a cold. Fluid builds up in the middle ear, creating a perfect breeding ground for bacteria or viruses to grow into an ear infection.

Pus forms as the body tries to fight the ear infection. More fluid collects and pushes against the eardrum, causing pain and sometimes problems hearing. Fever typically lasts a few days. And pain and crying usually last for several hours. After that, most children have some pain on and off for several days, although young children may have pain that comes and goes for more than a week.

Antibiotic treatment may shorten some symptoms. But most of the time the immune system can fight infection and heal the ear infection without the use of these medicines.

In severe cases, too much fluid can increase pressure on the eardrum until it ruptures, allowing the fluid to drain. When this happens, fever and pain usually go away and the infection clears. The eardrum usually heals on its own, often in just a couple of weeks.

Sometimes complications, such as an ear infection with chronic drainage, can occur with repeat ear infections.

Middle ear fluid buildup

Most children who have ear infections still have some fluid behind the eardrum a few weeks after the infection is gone. For some children, the fluid clears in about a month. And a few children still have fluid buildup (effusion) several months after an ear infection clears. This fluid buildup in the ear is called otitis media with effusion. Hearing problems can result, because the fluid affects how the middle ear works. Usually, infection does not occur.

Otitis media with fluid buildup (effusion) may occur even if a child has not had an obvious ear infection or upper respiratory infection. In these cases, something else has caused eustachian tube blockage.

In rare cases, complications can arise from middle ear infection or fluid buildup. Examples include hearing loss and ruptured eardrum.

What Increases Your Risk

Some things that increase the risk for middle ear infection are out of your control. These include:

- Age. Children ages 3 years and younger are most likely to get ear infections. Also, young children get more colds and other upper respiratory infections. Most children have at least one ear infection before they are 7 years old.

- Birth defects or other medical conditions. Babies with cleft palate or Down syndrome are more likely to get ear infections.

- Weakened immune system. Children with severely impaired immune systems have more ear infections than healthy children.

- Family history. Children are more likely to have repeat middle ear infections if a parent or sibling had repeat ear infections.

- Allergies. Allergies cause long-term stuffiness in the nose that can block one or both eustachian tubes, which connect the back of the nose and throat with the middle ears. This blockage can cause fluid to build up in the middle ear.

Other things that increase the risk for ear infection include:

- Repeat colds and upper respiratory infections. Most ear infections develop from these illnesses.

- Exposure to cigarette smoke. Babies who are around cigarette smoke are more likely to have ear infections than babies who are not. Also, ear infections seem to last longer in babies who are near cigarette smoke.

- Bottle-feeding. Bottle-fed babies are more likely to develop ear infections within the first year of life than babies who are breastfed. Also, bottle-fed babies may be more likely to get ear infections if they drink their bottles lying down rather than being held in an upright position.

- Child care centers. Children who are around many other children, such as in child care centers, are more likely to have repeat ear infections.

- Pacifier use. A young child who uses a pacifier is more likely to get ear infections.

Things that increase the risk for repeated ear infections also include:

- Ear infections at an early age. Babies who have their first ear infection before 6 months of age are more likely to have other ear infections.

- Persistent fluid in the ear. Fluid behind the eardrum that lasts longer than a few weeks after an ear infection increases the risk for repeated infection.

- Prior infections. Children who had an ear infection within the previous 3 months are more likely to have another ear infection, especially if the infection was treated with antibiotics.

When should you call your doctor?

Call your doctor immediately if:

- Your child has sudden hearing loss, severe pain, or dizziness.

- Your child seems to be very sick with symptoms such as a high fever and stiff neck.

- You notice redness, swelling, or pain behind or around your child’s ear, especially if your child doesn’t move the muscles on that side of his or her face.

Call your doctor if:

- You can’t quiet your child who has a severe earache by using home treatment over several hours.

- Your baby pulls or rubs his or her ear and appears to be in pain (crying, screaming).

- Your child’s ear pain increases even with treatment.

- Your child has a fever of 101°F (38.3°C) or higher with other signs of ear infection.

- You suspect that your child’s eardrum has burst, or fluid that looks like pus or blood is draining from the ear.

- Your child has an object stuck in his or her ear.

- Your child with an ear infection continues to have symptoms (fever and pain) after 48 hours of treatment with an antibiotic.

- Your child with an ear tube develops an earache or has drainage from his or her ear.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is when you and your doctor watch symptoms to see if the health problem improves on its own. If it does, no treatment is needed. If the symptoms don’t get better or if they get worse, then it’s time to take the next treatment step.

Your doctor may recommend watchful waiting if your child is age 6 months or older, has mild ear pain, and is otherwise healthy. Most ear infections get better without antibiotics. But if your child’s pain doesn’t get better with nonprescription children’s pain reliever (such as acetaminophen) or the symptoms continue after 48 hours, call a doctor.

Who to see

Health professionals who can diagnose and treat ear infections include:

- Pediatricians.

- Family medicine doctors.

- Nurse practitioners.

- Physician assistants.

- Internal medicine doctors.

- Otolaryngologists.

- Pediatric otolaryngologists.

Children who often get ear infections may need to see one of these specialists:

- Otolaryngologist

- Pediatric otolaryngologist

- Audiologist

Exams and Tests

Middle ear infections are usually diagnosed using a health history, a physical exam, and an ear exam.

The doctor uses a pneumatic otoscope to look at the eardrum for signs of an ear infection or fluid buildup. For example, the doctor can see if the eardrum moves freely when the pneumatic otoscope pushes air into the ear.

Other tests may include:

- Tympanometry, which measures how the eardrum responds to a change of air pressure inside the ear.

- Hearing tests. These tests are recommended for children who have had fluid in one or both ears (otitis media with effusion) for a total of 3 months. The tests may be done sooner if hearing loss is suspected.

- Tympanocentesis. This test can remove fluid if it has stayed behind the eardrum (chronic otitis media with effusion) or if infection continues even with antibiotics.

- Blood tests, which are done if there are signs of immune problems.

Treatment Overview

The first treatment of a middle ear infection focuses on relieving pain. The doctor will also assess your child for any risk of complications.

If your child’s condition improves in the first couple of days, treating the symptoms at home may be all that is needed. For more information, see Home Treatment.

If your child isn’t better after a couple of days of home treatment, call your doctor. He or she may prescribe antibiotics.

Follow-up exams with a doctor are important to check for persistent infection, fluid behind the eardrum (otitis media with effusion), or repeat infections. Even if your child seems well, he or she may need a follow-up visit in about 4 weeks, especially if your child is young.

Antibiotics

Your doctor can give your child antibiotics, but ear infections often get better without them. Talk about this with your doctor. Whether you use antibiotics will depend on how old your child is and how bad the infection is. For more information, see Medications.

If your child has cochlear implants, your doctor will probably prescribe antibiotics, because serious complications of ear infections, including bacterial meningitis, are more common in children who have cochlear implants than in children who do not have cochlear implants.

Repeat ear infections

If a child has repeat ear infections (three or more ear infections in a 6-month period or four in 1 year), you may want to consider treatment to prevent future infections.

One option that has been used a lot in the past is long-term oral antibiotic treatment. There is debate within the medical community about using antibiotics on a long-term basis to prevent ear infections. Many doctors don’t want to prescribe long-term antibiotics, because they are not sure that they really work. Also, when antibiotics are used too often, bacteria can become resistant to antibiotics.

Having tubes put in the ears is another option for treating repeat ear infections.

Fluid buildup and hearing problems

Fluid behind the eardrum after an ear infection is normal. And in most children, the fluid clears up within 3 months without treatment. If your child has fluid buildup without infection, you may try watchful waiting.

Have your child’s hearing tested if the fluid lasts longer than 3 months. If hearing is normal, you may choose to keep watching your child without treatment.

If a child has fluid behind the eardrum for more than 3 months and has significant hearing problems, then treatment is needed. Sometimes short-term hearing loss occurs, which is especially a concern in children ages 2 and younger. Normal hearing is very important when young children are learning to talk.

If your child is younger than 2, your doctor may not wait 3 months to start treatment. Hearing problems at this age could affect your child’s speaking ability. This is also why children in this age group are closely watched when they have ear infections.

If there is a hearing problem, your doctor may also prescribe antibiotics to keep the fluid in the ear from getting infected. The doctor might also suggest placing tubes in the ears to drain the fluid and improve hearing.

Surgery

Doctors may consider surgery for children who have repeat ear infections or for those who have persistent fluid behind the eardrum. Procedures include inserting ear tubes or removing adenoids and, in rare cases, the tonsils. For more information, see Surgery.

Treating other problems

Children who get rare but serious problems from ear infections, such as infection in the tissues around the brain and spinal cord (meningitis) or infection in the bone behind the ear (mastoiditis), need treatment right away.

Prevention

You may be able to prevent your child from getting middle ear infections.

- Don’t smoke. Ear infections are more common in children who are around cigarette smoke in the home. Even fumes from tobacco smoke on your hair and clothes can affect the child.

- Breastfeed your baby. There is some evidence that breastfeeding helps reduce the risk of ear infections, especially if they run in your family. If you bottle-feed, don’t let your baby drink a bottle while he or she is lying down.

- Wash your hands often. Hand-washing stops infection from spreading by killing germs.

- Make sure your child receives all the recommended immunizations. For more information, see the topic Immunizations.

- Take your child to a smaller child care center. Fewer children means less contact with bacteria and viruses. Try to limit the use of any group child care, where germs can easily spread.

- Do not give your baby a pacifier. Try to wean your child from his or her pacifier before about 6 months of age. Babies who use pacifiers after 12 months of age are more likely to get ear infections.

Home Treatment

Rest and care at home is often all that children ages 6 months and older need when they have an ear infection. Most ear infections get better without treatment. If your child is mildly ill and home treatment takes care of the earache, you may choose not to see a doctor.

At home, try these tips:

- Use pain relievers. Pain relievers such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (Advil, Aleve, and Motrin, for example) and acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) will help your child feel better. Giving your child something for pain before bedtime is especially important.

- Follow all instructions on the label. If you give medicine to your baby, follow your doctor’s advice about what amount to give.

- Do not give aspirin to anyone younger than 20, because it is linked to Reye syndrome, a serious illness.

- Apply heat to the ear, which may help with pain. Use a warm washcloth.

- Encourage rest. Resting will help the body fight the infection. Arrange for quiet play activities.

- Use eardrops. Doctors often suggest eardrops for earache pain. Don’t use eardrops without a doctor’s advice, especially if your child has tubes in his or her ears. For more information, see the safest way to insert eardrops.

If your child isn’t better after a few days of home treatment, call your doctor.

Care for ear tubes or ruptured eardrums

Ask your doctor if your child needs to take extra care to keep water from getting in the ears when there’s a hole or tube in the eardrum. Your child may need to wear earplugs. Check with your doctor to find out what he or she recommends.

Care during air travel

If your child with an ear infection must take an airplane trip, talk with your doctor about how to help your child cope with ear pain during the trip.

Medications

Antibiotics can treat ear infections caused by bacteria. But most children with ear infections get better without them. If the care you give at home relieves pain and the symptoms are getting better after a few days, you may not need antibiotics.

Your doctor will likely give antibiotics if:footnote 1

- Your child has an ear infection and appears very ill.

- Your child is younger than 2 and has an infection in both ears or has more than mild pain or fever.

- Your child is at risk for complications from the infection.

For children ages 6 months and older, many doctors wait for a few days to see if the ear infection will get better on its own. When doctors do prescribe antibiotics, they most often use amoxicillin, because it works well and costs less than other brands.

When your child takes antibiotics for an ear infection, it is very important to take all of the medicine as directed, even if your child feels better. Do not use leftover antibiotics to treat another illness. Misuse of antibiotics can lead to drug-resistant bacteria.

Deciding about antibiotics

Some doctors prefer to treat all ear infections with antibiotics, because it’s hard to tell which ear infections will clear up on their own. Some things to consider before your child takes antibiotics include:

- Risk for antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The greatest problem with using antibiotics to treat ear infections is the possibility of creating bacteria that can’t be killed by the usual antibiotics (antibiotic-resistant bacteria). Use antibiotics only when they’re needed.

- Side effects of antibiotics. Mild side effects, such as diarrhea and rash, from taking antibiotics are common. Severe side effects are rare.

- Cost. Most antibiotics are expensive. You may want to weigh the cost against the fact that most ear infections clear up without treatment.

Antibiotics have only minimal benefits in reducing pain and fever.

If your child still has symptoms (fever and earache) longer than 48 hours after starting an antibiotic, a different antibiotic may work better. Call your doctor if your child isn’t feeling better after 2 days of antibiotic treatment.

Other medicines

Other medicines that can treat symptoms of ear infection include:

- Acetaminophen (for example, Tylenol) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (for example, Advil, Aleve, and Motrin), for pain and fever. Follow all instructions on the label. If you give medicine to your baby, follow your doctor’s advice about what amount to give. Do not give aspirin to anyone younger than 20 because of its link to Reye syndrome, a serious illness.

- Some eardrops may help with severe earache. But do not use eardrops if the eardrum is ruptured. For more information, see the safest way to insert eardrops.

- Sometimes corticosteroids are given with antibiotics to get rid of fluid behind the eardrum. Steroid medicines are not a good choice for treating ear infections. Do not use them if a child has been around someone with chickenpox within the last 3 weeks.

Most studies find that decongestants, antihistamines, and other nonprescription cold remedies usually don’t help prevent or treat ear infections or fluid behind the eardrum. Antihistamines that may make your child sleepy can thicken fluids and may actually make your child feel worse. Check with the doctor before giving these medicines to your child. Experts say not to give decongestants to children younger than 2 years.

Surgery

Ear tube placement

Surgery for middle ear infections often means placing a drainage tube into the eardrum of one or both ears. It’s one of the most common childhood operations.

Inserting ear tubes (myringotomy or tympanostomy with tube placement):

- May help to relieve hearing problems.

- Helps prevent buildup of pressure and fluid in the middle ear.

- Allows fluid to drain from the middle ear.

- Ventilates the middle ear after the fluid is gone.

- May prevent repeat ear infections.

While the child is under general anesthesia, the surgeon cuts a small hole in the eardrum and inserts a small plastic tube in the opening.

Most tubes stay in place for about 6 to 12 months and then usually fall out on their own. After the tubes are out, the hole in the eardrum usually closes in 3 to 4 weeks. Some children need tubes put back in their ears because fluid behind the eardrum returns.

In rare cases, tubes may scar the eardrum and lead to permanent hearing loss.

Deciding about ear tubes

Doctors consider tube placement for children who have had repeat infections or fluid behind the eardrum in both ears for 3 to 4 months and have trouble hearing. Sometimes they consider tubes for a child who has fluid in only one ear but also has trouble hearing. Learn the pros and cons of this surgery. Before deciding, ask how the surgery can help or hurt your child and how much it will cost.

Care after ear tubes are placed

Ask your doctor if your child needs to take extra care to keep water from getting in the ears when bathing or swimming. Your child may need to wear earplugs. Check with your doctor to find out what he or she recommends.

You can use antibiotic eardrops for ear infections while tubes are in place. In some cases, antibiotic eardrops seem to work better than antibiotics by mouth when tubes are present.footnote 2

Adenoids and/or tonsil removal

Adenoid removal (adenoidectomy) or adenoid and tonsil removal (adenotonsillectomy) may help some children who have repeat ear infections or fluid behind the eardrum. Children younger than 4 don’t usually have their adenoids taken out unless they have severe nasal blockage.

As a treatment for chronic ear infections, experts recommend removing adenoids and tonsils only after tubes and antibiotics have failed. Removing adenoids may improve air and fluid flow in nasal passages. This may reduce the chance of fluid collecting in the middle ear, which can lead to infection. When used along with other treatments, removing adenoids (adenoidectomy) can help some children who have repeat ear infections. But taking out the tonsils with the adenoids (adenotonsillectomy) isn’t very helpful.footnote 3 Tonsils are removed if they are frequently infected. Experts don’t recommend tonsil removal alone as a treatment for ear infections.footnote 4

Ruptured eardrum

Surgeons sometimes operate to close a ruptured eardrum that hasn’t healed in 3 to 6 months, though this is rare. The eardrum usually heals on its own within a few weeks. If a child has had many ear infections, you may delay surgery until the child is 6 to 8 years old to allow time for eustachian tube function to improve. At this point, there is a better chance that surgery will work.

Other Treatment

Allergy treatment can help children who have allergies and who also have frequent ear infections. Allergy testing isn’t suggested unless children have signs of allergies.

Some people use herbal remedies, such as echinacea and garlic oil capsules, to treat ear infections. There is no scientific evidence that these therapies work. If you are thinking about using these therapies for your child’s ear infection, talk with your doctor.

Related Information

- Hand-Washing

- Ear Problems and Injuries, Age 11 and Younger

- Quick Tips: Safely Giving Over-the-Counter Medicines to Children

- Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) Infection

- Using Antibiotics Wisely

- Colds

- Ear Problems and Injuries, Age 12 and Older

- Labyrinthitis and Vestibular Neuritis

- Ear Canal Problems (Swimmer’s Ear)

- Choosing Child Care

- Blocked Eustachian Tubes

References

Citations

- American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Family Physicians (2013). Clinical practice guideline: Diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics, 131(3): e964–e999.

- Klein JO (2011). Infections of the ear. In CD Rudolph et al., eds., Rudolph’s Pediatrics, 22nd ed., pp. 973–979. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Williamson I (2015). Otitis media with effusion in children. BMJ Clinical Evidence. http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/systematic-review/0502/overview.html. Accessed April 14, 2016.

- Pai S, Parikh SR (2012). Otitis media. In AK Lalwani, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed., pp. 674–681. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Other Works Consulted

- An expanded pneumococcal vaccine (Prevnar 13) for infants and children (2010). Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics, 52(1345): 67–68.

- Berkman ND, et al. (2013) Otitis Media With Effusion: Comparative Effectiveness of Treatments. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 101. (AHRQ Publication No. 13-EHC091-EF). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: http://www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm.

- Kerschner JE (2011). Otitis media. In RM Kleigman et al., eds., Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed., pp. 2199–2213. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Klein JO, Bluestone CD (2009). Otitis media. In RD Feigin et al., eds., Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 6th ed., vol. 1, pp. 216–236. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

- Morris P (2012). Chronic suppurative otitis media. BMJ Clinical Evidence. http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/pdf/clinical-evidence/en-gb/systematic-review/0507.pdf. Accessed March 12, 2014.

- Pai S, Parikh SR (2012). Otitis media. In AK Lalwani, ed., Current Diagnosis and Treatment Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, 3rd ed., pp. 674–681. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Shekelle PG, et al. (2010). Management of Acute Otitis Media: Update. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 198. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/tp/otitisuptp.htm.

- Venekamp RP, et al. (2014). Acute otitis media in children. BMJ Clinical Evidence. http://clinicalevidence.bmj.com/x/systematic-review/0301/overview.html. Accessed April 14, 2016.

Current as of: October 21, 2018

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Susan C. Kim, MD – Pediatrics & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & John Pope, MD, MPH – Pediatrics

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.