Farsightedness (Hyperopia)

Topic Overview

What is farsightedness?

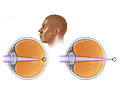

People who are farsighted see things at a distance more easily than they see things up close. If you are very farsighted, close objects may be so blurry that you can’t do tasks such as reading or sewing. A farsighted eye sees things differently than an eye that is not farsighted.

Farsightedness (hyperopia) is usually a variation from normal, not a disease. How it affects you will likely change as you age.

What causes farsightedness?

Farsightedness occurs when light entering the eye is focused behind the retina instead of directly on it. This is caused by an eye that is too short, whose cornea is not curved enough, or whose lens sits farther back in the eye than normal.

Farsightedness often runs in families. In rare cases, some diseases such as retinopathy and eye tumors can cause it.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of farsightedness can include:

- Blurred vision, especially at night.

- Trouble seeing objects up close. For example, you can’t see well enough to read newspaper print.

- Aching eyes, eyestrain, and headaches.

Children with this problem may have no symptoms. But a child with more severe farsightedness may:

- Have headaches.

- Rub his or her eyes often.

- Have trouble reading or show little interest in reading.

When does farsightedness start? How does it change over time?

Farsightedness often starts in early childhood. But normal growth corrects the problem. If a child is still a bit farsighted when the eye has stopped growing (at around 9 years of age), the eye can usually adjust to make up for the problem. This is called accommodation.

But as we age, our eyes can no longer adjust as well. Starting at about age 40, our eyes naturally begin to lose the ability to focus on close objects. This is called presbyopia. You may start to notice that your near vision becomes blurred. As presbyopia gets worse, both near and distance vision will become blurred.

How is farsightedness diagnosed?

A routine eye exam by an ophthalmologist or optometrist can show whether you are farsighted. The eye exam includes questions about your eyesight and a physical exam of your eyes. Ophthalmoscopy, tonometry, a slit lamp exam, and other vision tests are also part of a routine eye exam.

Eye exams should be done for new babies and at all well-child visits.

How is it treated?

Most farsighted people don’t need treatment. Your eyes can usually adjust to make up for the problem. But as you age and your eyes can’t adjust as well, you will probably need eyeglasses or contact lenses. (Glasses or contact lenses can help at any age if farsightedness is more than a mild problem.)

Surgery may be an option in some cases. Procedures to reshape the cornea, such as LASIK, can be done for milder cases of farsightedness. For severe farsightedness, surgery can replace the clear lens of your eye with an implanted lens.

But many eye specialists question whether these procedures are a good choice. Most farsighted people can have very good vision with glasses or contact lenses. Farsightedness is not a disease, and most farsighted eyes are otherwise normal and healthy.

If you are farsighted, get regular eye exams, and see your eye care specialist if you have changes in your vision.

References

Other Works Consulted

- American Academy of Ophthalmology (2017). Refractive Errors and Refractive Surgery (Preferred Practice Pattern). San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology. https://www.aao.org/ppp. Accessed July 20, 2018.

- Chong NV (2011). Lasers in ophthalmology. In P Riordan-Eva, ET Cunningham, eds., Vaughan and Asbury’s General Ophthalmology, 18th ed., pp. 431–439. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Riordan-Eva P (2011). Optics and refraction. In P Riordan-Eva, ET Cunningham, eds., Vaughan and Asbury’s General Ophthalmology, 18th ed., pp. 396–411. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Current as of: May 5, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Christopher Joseph Rudnisky, MD, MPH, FRCSC – Ophthalmology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.