Immunoglobulins

Test Overview

An immunoglobulins test is done to measure the level of immunoglobulins, also known as antibodies, in your blood.

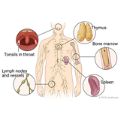

Antibodies are substances made by the body’s immune system in response to bacteria, viruses, fungus, animal dander, or cancer cells. Antibodies attach to the foreign substances so the immune system can destroy them.

Antibodies are specific to each type of foreign substance. For example, antibodies made in response to a tuberculosis infection attach only to tuberculosis bacteria. Antibodies also work in allergic reactions. Occasionally, antibodies may be made against your own tissues. This is called an autoimmune disease.

If your immune system makes low levels of antibodies, you may have a greater chance of developing repeated infections. You can be born with an immune system that makes low levels of antibodies, or your system may make low levels of antibodies in response to certain diseases, such as cancer.

The five major types of antibodies are:

- IgA. IgA antibodies are found in areas of the body such the nose, breathing passages, digestive tract, ears, eyes, and vagina. IgA antibodies protect body surfaces that are exposed to outside foreign substances. This type of antibody is also found in saliva, tears, and blood. About 10% to 15% of the antibodies present in the body are IgA antibodies. A small number of people do not make IgA antibodies.

- IgG. IgG antibodies are found in all body fluids. They are the smallest but most common antibody (75% to 80%) of all the antibodies in the body. IgG antibodies are very important in fighting bacterial and viral infections. IgG antibodies are the only type of antibody that can cross the placenta in a pregnant woman to help protect her baby (fetus).

- IgM. IgM antibodies are the largest antibody. They are found in blood and lymph fluid and are the first type of antibody made in response to an infection. They also cause other immune system cells to destroy foreign substances. IgM antibodies are about 5% to 10% of all the antibodies in the body.

- IgE. IgE antibodies are found in the lungs, skin, and mucous membranes. They cause the body to react against foreign substances such as pollen, fungus spores, and animal dander. They are involved in allergic reactions to milk, some medicines, and some poisons. IgE antibody levels are often high in people with allergies.

- IgD. IgD antibodies are found in small amounts in the tissues that line the belly or chest. How they work is not clear.

The levels of each type of antibody can give your doctor information about the cause of a medical problem.

Why It Is Done

A test for immunoglobulins (antibodies) in the blood is done to:

- Find certain autoimmune diseases or allergies.

- Find certain types of cancer (such as multiple myeloma or macroglobulinemia).

- See whether recurring infections are caused by a low level of immunoglobulins (especially IgG).

- Check the treatment for certain types of cancer affecting the bone marrow.

- Check the treatment for Helicobacter pylori ( H. pylori) bacteria.

- Check the response to immunizations to see if you are immune to the disease.

- Check to see if you have an infection or have had it in the past.

This test is often done when the results of a blood protein electrophoresis or total blood protein test are abnormal.

How It Is Done

The health professional drawing blood will:

- Wrap an elastic band around your upper arm to stop the flow of blood. This makes the veins below the band larger so it is easier to put a needle into the vein.

- Clean the needle site with alcohol.

- Put the needle into the vein. More than one needle stick may be needed.

- Attach a tube to the needle to fill it with blood.

- Remove the band from your arm when enough blood is collected.

- Put a gauze pad or cotton ball over the needle site as the needle is removed.

- Put pressure on the site and then put on a bandage.

How It Feels

The blood sample is taken from a vein in your arm. An elastic band is wrapped around your upper arm. It may feel tight. You may feel nothing at all from the needle, or you may feel a quick sting or pinch.

Risks

There is very little chance of a problem from having a blood sample taken from a vein.

- You may get a small bruise at the site. You can lower the chance of bruising by keeping pressure on the site for several minutes.

- In rare cases, the vein may become swollen after the blood sample is taken. This problem is called phlebitis. A warm compress can be used several times a day to treat this.

Results

An immunoglobulins test is done to measure the level of immunoglobulins, also known as antibodies, in your blood.

Normal

The normal values listed here—called a reference range—are just a guide. These ranges vary from lab to lab, and your lab may have a different range for what’s normal. Your lab report should contain the range your lab uses. Also, your doctor will evaluate your results based on your health and other factors. This means that a value that falls outside the normal values listed here may still be normal for you or your lab.

The results listed below are normal values for adults. Children have different values than adults. Results are ready in several days.

|

IgA |

60–400 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or 600–4,000 milligrams per liter (mg/L) |

|

IgG |

700–1,500 mg/dL or 7.0–15.0 grams per liter (g/L) |

|

IgM |

60–300 mg/dL or 600–3,000 mg/L |

|

IgD |

0–14 mg/dL or 0–140 mg/L |

|

IgE |

3–423 international units per milliliter (IU/mL) or 3–423 kilo-international units per liter (kIU/L) |

High values

- IgA. High levels of IgA may mean that monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance (MGUS)or multiple myeloma is present. Levels of IgA also get higher in some autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and in liver diseases, such as cirrhosis and long-term (chronic) hepatitis.

- IgG. High levels of IgG may mean a long-term (chronic) infection, such as HIV, is present. Levels of IgG also get higher in IgG multiple myeloma, long-term hepatitis, and multiple sclerosis (MS). In multiple myeloma, tumor cells make only one type of IgG antibody (monoclonal); the other conditions cause an increase in many types of IgG antibodies (polyclonal).

- IgM. High levels of IgM can mean macroglobulinemia, early viral hepatitis, mononucleosis, rheumatoid arthritis, kidney damage (nephrotic syndrome), or a parasite infection is present. Because IgM antibodies are the type that form when an infection occurs for the first time, high levels of IgM can mean a new infection is present. High levels of IgM in a newborn mean that the baby has an infection that started in the uterus before delivery.

- IgD. How IgD works in the immune system is not clear. A high level may mean IgD multiple myeloma is present. IgD multiple myeloma is much less common than IgA or IgG multiple myeloma.

- IgE. A high level of IgE can mean a parasite infection is present. Also, high levels of IgE often are found in people who have allergic reactions, asthma, atopic dermatitis, some types of cancer, and certain autoimmune diseases. In rare cases, a high level of IgE may mean IgE multiple myeloma.

Low values

- IgA. Some people are born with low or absent levels of IgA antibodies. Low levels of IgA occur in some types of leukemia, kidney damage (nephrotic syndrome), a problem with the intestines (enteropathy), and a rare inherited disease that affects muscle coordination (ataxia-telangiectasia). A low level of IgA increases the chance of developing an autoimmune disease.

- IgG. Low levels of IgG occur in macroglobulinemia. In this disease, the high levels of IgM antibodies stop the growth of cells that make IgG. Other conditions that can cause low levels of IgG include some types of leukemia and a type of kidney damage (nephrotic syndrome). In rare cases some people are born with a lack of IgG antibodies. These people are more likely to develop infections.

- IgM. Low levels of IgM occur in multiple myeloma, some types of leukemia, and in some inherited types of immune diseases.

- IgE. Low levels of IgE can occur in a rare inherited disease that affects muscle coordination (ataxia-telangiectasia).

What Affects the Test

Reasons you may not be able to have the test or why the results may not be helpful include:

- Taking certain medicines. Be sure your doctor knows all of the medicines you take. Some medicines that affect test results include ones used for birth control, heart failure, seizures, and rheumatoid arthritis.

- Having cancer treatments, both radiation and chemotherapy.

- Receiving a blood transfusion in the past 6 months.

- Getting vaccinations (immunizations), especially vaccinations with repeat (booster) doses, in the past 6 months.

- Using alcohol or illegal drugs.

- Having had a radioactive scan in the past 3 days.

What To Think About

- Immunoglobulins are made specific to different illnesses. For example, the IgM antibody for mononucleosis is different than the IgM for herpes. For this reason, a doctor can look for an immunoglobulin to a specific illness to help diagnose that illness.

- Different antibodies can be used to help a doctor tell the difference between a new and past infection. For example, IgM antibodies for mononucleosis with or without IgG antibodies means a new mono infection. IgG antibodies without IgM means a past mono infection.

- People with very low immunoglobulin levels, especially IgA, IgG, and IgM, have a higher chance of developing an infection.

- A very small number of people cannot make IgA and have a higher chance of developing a potentially life-threatening reaction to a blood transfusion.

- An immunoglobulin test is often done when the results of a blood protein electrophoresis or total blood protein test are abnormal.

References

Citations

- Fischbach FT, Dunning MB III, eds. (2009). Manual of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Other Works Consulted

- Chernecky CC, Berger BJ (2008). Laboratory Tests and Diagnostic Procedures, 5th ed. St. Louis: Saunders.

- Fischbach FT, Dunning MB III, eds. (2009). Manual of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests, 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- Pagana KD, Pagana TJ (2010). Mosby’s Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier.

Current as of: March 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.