Lumbar Spinal Stenosis

Topic Overview

Is this topic for you?

This topic is about spinal stenosis of the lower back, also known as the lumbar area. If you need information on spinal stenosis of the neck, see the topic Cervical Spinal Stenosis.

What is lumbar spinal stenosis?

Lumbar spinal stenosis is a narrowing of the spinal canal in the lower back, known as the lumbar area.

This usually happens when bone or tissue—or both—grow in the openings in the spinal bones. This growth can squeeze and irritate nerves that branch out from the spinal cord.

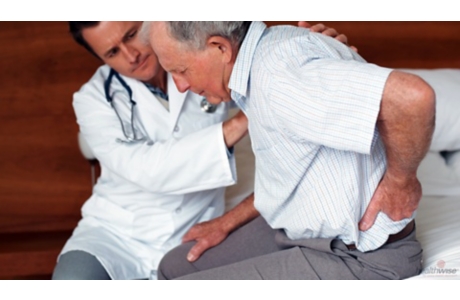

The result can be pain, numbness, or weakness, most often in the legs, feet, and buttocks.

What causes lumbar spinal stenosis?

It’s most often caused by changes that can happen as people age. For example:

- Connective tissues called ligaments get thicker.

- Arthritis leads to the growth of bony spurs that push on the nerves that branch out from the spinal cord.

- Discs between the bones may be pushed backward into the spinal canal.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms may include:

- Numbness, weakness, cramping, or pain in the legs, feet, or buttocks. These symptoms get worse when you walk, stand straight, or lean backward. The pain gets better when you sit down or lean forward.

- Stiffness in the legs and thighs.

- Low back pain.

- In severe cases, loss of bladder and bowel control.

Symptoms may be severe at times and not as bad at other times. Most people aren’t severely disabled. In fact, many people don’t have symptoms at all.

How is lumbar spinal stenosis diagnosed?

Your doctor can tell if you have it by asking questions about your symptoms and past health and by doing a physical exam.

You will probably need imaging tests such as an MRI, a CT scan, and sometimes X-rays.

How is it treated?

You can most likely control mild to moderate symptoms with pain medicines, exercise, and physical therapy. Your doctor may also give you a spinal shot of corticosteroid, a medicine that reduces inflammation.

You may need surgery if your symptoms get worse or if they limit what you can do. Surgery to remove bone and tissue that are squeezing the nerve roots can help relieve leg pain and allow you to get back to normal activity. But it may not help back pain as much.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

The most common cause of lumbar spinal stenosis is changes in the spine that can happen as you get older.

These changes include thickening of soft tissues, development of bony spurs, and gradual breakdown of spinal discsand joints. Any of these conditions can narrow the spinal canal.

Spinal stenosis usually happens gradually. Symptoms may start when the changes begin to squeeze the spinal cord or its nerve roots.

These age-related changes often happen when you have certain disorders:

- Arthritis of the spine wears away joint cartilage and causes bony growths (spurs).

- Certain bone diseases, such as Paget’s disease and ankylosing spondylitis, may soften the spinal bones or cause too much bone to grow.

Also, other conditions may cause spinal stenosis, such as:

- An abnormally narrow spinal canal, which can be an inherited condition.

- Spondylolysis, which is a defect or fracture on one or both of the wing-shaped parts of a vertebra. A vertebra may slide forward or backward over the bone below and may squeeze the spinal cord or a nerve root.

- Spinal fracture.

- Cancer.

- Fibrosis, which is excess, ropy tissue much like scar tissue. It can come from having spine surgery in the past.

Symptoms

Many people, especially those older than age 50, have some narrowing of the spinal canal but don’t have symptoms.

Symptoms occur when the nerve roots get squeezed.

Leg pain

The most common symptom is leg pain that happens when you walk or stand and feels better when you sit. You feel pain in your legs, because the nerve roots that pass through the lower spine extend to the legs.

People often have leg pain when the spine is extended—when they are standing straight or leaning backward, for example.

And they often feel better when the spine is flexed—when they are sitting, walking uphill, riding a bicycle, or leaning over a grocery cart, for example.

People with severe stenosis may have a habit of leaning forward in a stooped position to relieve pain.

Other symptoms

Other symptoms may include:

- Numbness, weakness, and cramping in the legs, feet, or buttocks.

- Stiffness in the legs and thighs.

- Low back pain.

- In severe cases, loss of bladder and bowel control.

Several other conditions have symptoms similar to spinal stenosis.

What Happens

Lumbar spinal stenosis usually starts gradually and gets worse over a long period of time. Narrowing of the spinal canal can squeeze and irritate the nerve roots that branch out from the spinal cord. This is what causes pain and other symptoms.

Stenosis occurs most often in the lower back (lumbar) area. When it occurs in the neck, it is called cervical spinal stenosis.

The course of spinal stenosis varies—it may stay the same, get better, or get worse.

Severe disability isn’t common. But when symptoms are very bad, they can keep you from doing your normal daily activities. They can have a big effect your quality of life. If symptoms are still severe after you have tried other treatment for a while, surgery may be considered.

Surgery may be too risky for some older adults who have other serious health problems.

What Increases Your Risk

The risk of having lumbar spinal stenosis increases if you:

- Are older than age 50.

- Have a history of spinal injury.

- Have arthritis of the spine, which can damage the joints.

- Have a bone disease that may soften the spinal bones or cause calcium deposits to form. Examples include:

- Are born with spondylolysis.

- Have an abnormally narrow spinal canal, which may be inherited or may develop in curvature of the spine (scoliosis).

- Have a genetic (inherited) disorder in which the bones of the arms and legs don’t grow to normal size and the vertebrae of the spine don’t grow normally (achondroplastic dwarfism).

- Have had lower back surgery, which may cause scarring that puts pressure on the spinal nerves. Progressive spinal stenosis may occur, even after successful back surgery.

When should you call your doctor?

Call 911 or other emergency services immediately if a person has signs of damage to the spine after an injury (such as a car accident, fall, or direct blow to the spine). Signs may include severe back pain, or weakness, tingling, or numbness in one or both legs.

Call your doctor nowif:

- You have a new loss of bowel or bladder control.

- Leg pain is accompanied by persistent weakness, tingling, or numbness in any part of the leg from the buttock to the ankle or foot.

- Low back pain is accompanied by vomiting, fever, or both.

- Leg pain, weakness, numbness that comes and goes (intermittent), or tingling lasts longer than 1 week even though you use home treatment.

- Significant back pain either does not improve or gets worse over 2 weeks.

Watchful waiting

Lumbar spinal stenosis usually gets worse gradually over months to years. If you have symptoms that come on suddenly, you may have another serious condition and should call your doctor.

If you begin to regularly have leg pain when walking and standing, call your doctor.

Who to see

The following health professionals can diagnose and treat spinal stenosis:

- Family medicine physician

- Internist

- Nurse practitioner

- Physician assistant

- Emergency medicine (ER) doctor

Specialists who can treat spinal stenosis include the following:

- Orthopedist/orthopedic surgeon, including surgeons who specialize in the spine

- Neurologist or neurosurgeon

- Rheumatologist

- Physiatrist

- Physical therapist

Exams and Tests

Lumbar spinal stenosis can usually be diagnosed based on your history of symptoms, a physical exam, and imaging tests—tests that produce various kinds of pictures of your body. These tests include:

- MRI, to check your spinal nerves and look for disc problems.

- CT scan, to check your bones and joints.

- X-rays, to measure the extent of arthritis or injuries to the vertebrae.

- Bone scan, to rule out cancer and other bone diseases.

- Electromyogram and nerve conduction tests to see if other problems may be causing or adding to your symptoms.

- Myelogram, to look for narrowing of the spinal canal or abnormalities of the nerves branching off the canal. This is rarely used to diagnose spinal stenosis.

Your doctor may try nonsurgical treatment, such as pain-relieving medicines, exercise, and physical therapy, for a period of time before ordering imaging tests. If treatment works, you may not need tests.

Imaging tests can help confirm a diagnosis or rule out other problems. But even if imaging shows spinal stenosis, your symptoms may not match the results of the tests. So treatment is based on what your symptoms are and how much spinal stenosis is impacting your life, not just on the results of imaging tests.

Treatment Overview

The goals of treatment for spinal stenosis are to relieve pain, numbness, and weakness in the legs, to make it easier for you to move around, and to improve your quality of life.

Treatments include:

- Home treatment, such as exercising, using over-the-counter pain medicines, and losing extra weight.

- Prescription medicines to relieve pain.

- Physical therapy, to provide education, instruction, and support for your self-care.

- Surgery, although most cases don’t need this treatment.

Prevention

You can’t always prevent changes in your back that may come with aging. But you may be able to limit spinal stenosis symptoms by keeping your back as healthy as possible:

- Get regular exercise, including flexibility stretches.

- Stay at a healthy weight.

- Have good posture.

- Don’t smoke. Smoking has been linked to back pain and disc problems. It decreases your bone density and increases your risk of fracture and bone deterioration. Also, smoking can make it harder for the bone to heal after a spinal fusion.

Home Treatment

You can take steps to treat lumbar spinal stenosis symptoms at home:

- Learn about stenosis and about how to relieve symptoms.

- Taking medicines, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen, to relieve pain. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

- Lose extra weight, which not only can relieve symptoms but also can slow progression of the stenosis.

- Exercise. Aerobic exercise as well as stretching and strengthening exercises for the lower back and stomach muscles can relieve symptoms and improve muscle strength, especially when done 4 or 5 times a week. The most helpful aerobic exercises include riding a stationary bike (with the spine flexed in a forward position) and walking on a treadmill with an incline.

- Restrict activities that make your symptoms worse. Depending on the severity and location of your stenosis, these activities might include walking (especially walking downhill) and standing for a length of time.

Be sure to talk with your doctor before you start home treatment.

Prevent falls

Pain and numbness in your legs can increase your risk of losing your balance. Falling can make symptoms worse. Take steps to lower your risk of falling:

- Limit your use of alcohol and sedative medicines, including flurazepam (Dalmane) and diazepam (such as Valium). They cause drowsiness and dizziness.

- Remove household hazards: slippery floors, poor lighting, electrical cords, cluttered walkways, and throw rugs.

- Take medicines only as directed by your doctor. Review medicines regularly with your primary care doctor, especially if you have more than one doctor prescribing them. Medicines like sleeping pills and pain relievers may increase your risk for falling.

- Wear low-heeled shoes that fit well.

Medications

Taking medicine along with other nonsurgical treatment is often enough to relieve pain and allow you to do normal daily activities. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

Medicine choices

Medicines used to relieve the symptoms of spinal stenosis include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as naproxen and ibuprofen. They may relieve pain and reduce inflammation.

- Acetaminophen, which may relieve pain but doesn’t reduce inflammation. If you can’t take NSAIDs, you can try acetaminophen.

- Opioid pain relievers, to relieve severe pain that does not respond to other medicines. Opioids are usually used only for short periods of time, to help avoid side effects.

- Epidural steroid injections (ESIs). These are sometimes tried to help leg pain by reducing inflammation in the nerve root.

Surgery

Surgery is done to relieve pressure on the nerve roots. This can help reduce pain, numbness, and weakness in your legs.

Surgery may be recommended if:

- Your pain, numbness, or weakness is so bad that it gets in the way of normal daily activities and hurts your quality of life.

- You are in otherwise good health.

The goal of surgery is to relieve pain, numbness, or weakness in the legs—not to relieve back pain. People who have surgery only for back pain are less satisfied with the results than are those who have surgery for nerve root symptoms and pain in both the back and legs. Also, numbness, weakness, and pain may return after surgery.

Surgery choices

Decompressive laminectomy, which relieves pressure on the spinal nerve roots, is the most common procedure for relieving spinal stenosis. This surgery may be done with or without spinal fusion.

Other Treatment

Physical therapy is an important treatment for spinal stenosis. It can help with pain and build muscle strength.

Your physical therapist may teach you exercises to strengthen your abdominal (belly) muscles, which will help support your spine. You may also learn exercises to help maintain flexibility and reduce inflammation.

Alternative and complementary medicine therapies, such as acupuncture, are used by some people to relieve pain from spinal stenosis.

Small metal devices can be inserted between the bones of the spine, near where the nerve roots leave the spinal cord. These are called interspinous process devices. The idea is to create more space between the bones, to take pressure off the nerve roots. This procedure may be an option for some people.

References

Other Works Consulted

- American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and American Academy of Pediatrics. (2010). Lumbar spinal stenosis. In JF Sarwark, ed., Essentials of Musculoskeletal Care, 4th ed., pp. 957–960. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- Atlas SJ, et al. (2005). Long-term outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica secondary to a lumbar disc herniation: 10-year results from the Maine Lumbar Spine Study. Spine, 30(8): 927–935.

- Chou R, et al. (2009). Interventional therapies, surgery and interdisciplinary rehabilitation for low back pain: An evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society. Spine, 34(10): 1066–1077.

- Djurasovic M, et al. (2010). Contemporary management of symptomatic lumbar spinal stenosis. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 41(2): 183–191.

- Friedly JL, et al. (2014) A randomized trial of epidural glucocorticoid injections for spinal stenosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 371(1): 11–21. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1313265. Accessed February 5, 2015.

- Isaac Z, Lopez E (2015). Lumbar spinal stenosis. In WR Frontera et al., eds., Essentials of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 3rd ed., pp. 257–263. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Mercier LR (2008). Lumbar spine stenosis section of The back. In Practical Orthopedics, 6th ed., pp. 152–153. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier.

- Resnick D, et al. (2005). Guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine—Part 9: Fusion in patients with stenosis and spondylolisthesis. Journal of Neurosurgery, 2: 679–685.

- Resnick DK, et al. (2005). Guidelines for the performance of fusion procedures for degenerative disease of the lumbar spine—Part 10: Fusion following decompression in patients with stenosis without spondylolisthesis. Journal of Neurosurgery, 2(6): 686–691.

- Tay BKB, et al. (2014). Disorders, diseases, and injuries of the spine. In HB Skinner, PJ McMahon, eds., Current Diagnosis and Treatment in Orthopedics, 5th ed., pp. 156–229. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Weinstein JN, et al. (2007). Surgical versus nonsurgical treatment for lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis. New England Journal of Medicine, 356(22): 2257–2270.

Current as of: June 26, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:William H. Blahd Jr. MD, FACEP – Emergency Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Kenneth J. Koval MD – Orthopedic Surgery, Orthopedic Trauma

Spinal Stenosis: Lumbar

Spinal Stenosis: Lumbar Spinal canal

Spinal canal Spinal cord anatomy

Spinal cord anatomy Discs of the Spine

Discs of the Spine Cartilage

Cartilage Nerves most often affected by lumbar spinal stenosis

Nerves most often affected by lumbar spinal stenosis Spinal Stenosis: Cervical

Spinal Stenosis: Cervical Deciding About Spinal Stenosis Surgery

Deciding About Spinal Stenosis Surgery Spinal Stenosis Surgery: How Others Decided

Spinal Stenosis Surgery: How Others Decided Back Surgery for Spinal Stenosis

Back Surgery for Spinal Stenosis Spinal Stenosis: Home Treatment and Physical Therapy

Spinal Stenosis: Home Treatment and Physical Therapy

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.