Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

Topic Overview

What is multiple sclerosis?

Multiple sclerosis, often called MS, is a disease that affects the central nervous system—the brain and spinal cord. It can cause problems with muscle control and strength, vision, balance, feeling, and thinking.

Your nerve cells have a protective covering called myelin. Without myelin, the brain and spinal cord can’t communicate with the nerves in the rest of the body. MS gradually destroys myelin in patches throughout the brain and spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and other symptoms. These patches of damage are called lesions.

MS is different for each person. You may go through life with only minor problems. Or you may become seriously disabled. Most people are somewhere in between. Generally, MS follows one of four courses:

- Relapsing-remitting, where symptoms fade and then return off and on for many years.

- Secondary progressive, which at first follows a relapsing-remitting course and then becomes progressive. “Progressive” means it steadily gets worse.

- Primary progressive, where the disease is progressive from the start.

- Progressive relapsing, where the symptoms are progressive at first and are relapsing later.

What causes MS?

The exact cause is unknown, but most experts believe that MS is an autoimmune disease. In this kind of disease, the body’s defenses, called the immune system, mistakenly attack normal tissues. In MS, the immune system attacks the central nervous system—the brain and spinal cord.

Experts don’t know why MS happens to some people but not others. There may be a genetic link, because the disease seems to run in families. Where you grew up may also play a role. MS is more common in those who grew up in colder regions that are farther away from the equator.

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms depend on which parts of the brain and spinal cord are damaged and how bad the damage is. Early symptoms may include:

- Muscle problems. You may feel weak and stiff, and your limbs may feel heavy. You may drag your leg when you walk.

- Vision problems. Your vision may be blurred or hazy. You may have eyeball pain (especially when you move your eyes), blindness, or double vision.

- Sensory problems. You may feel tingling, a pins-and-needles sensation, or numbness. You may feel a band of tightness around your trunk or limbs.

- Balance problems. You may feel lightheaded or dizzy or feel like you’re spinning.

How is MS diagnosed?

Diagnosing MS isn’t always easy. The first symptoms may be vague. And many of the symptoms can be caused by problems other than MS.

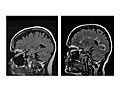

MS is not diagnosed unless a doctor can be sure that you have had at least two attacks affecting at least two different areas of your central nervous system. The doctor will examine you, ask you questions about your symptoms, and do some tests. An MRI is often used to confirm the diagnosis, because the patches of damage (lesions) caused by MS attacks can be seen with this test.

How is it treated?

Medicines are used to treat MS:

- During a relapse, to make the attack shorter and less severe.

- Over a long period of time, to keep down the number of attacks and how severe they are and to slow the progression of the disease. (This is called disease-modifying therapy.)

- To control specific symptoms.

You may find it hard to decide when to start taking the drugs that slow the progression of MS. The drugs may not work for everyone, and they often have side effects. You and your doctor will decide together when you should start any of these drugs.

How do you live with MS?

There is no cure for MS. Treatment and self-care can help you maintain your quality of life.

Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy can help you manage some physical problems caused by MS. You can also help yourself at home by eating balanced meals, getting regular exercise and rest, and learning to use your energy wisely.

Dealing with the physical and emotional demands of MS isn’t easy. If you feel overwhelmed, talk to your doctor. You may be depressed, which can be treated. And finding a support group where you can talk to other people who have MS can be very helpful.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

The cause of multiple sclerosis (MS) is unknown. Because a person’s risk of MS is slightly higher in some families when a relative has MS, there may be a genetic link. For more information, see What Increases Your Risk.

Some research suggests that where you lived as a child and viral illnesses you have had could be triggers for MS later in life. But these links have not been proved.

Symptoms

The symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) vary from person to person depending on which parts of the brain or spinal cord (central nervous system) are damaged. The loss of myelin and scarring caused by MS can affect any part of the central nervous system. Myelin is the insulating coating around a nerve.

Symptoms may come and go or become more or less severe from day to day or, in rare cases, from hour to hour. Symptoms may become worse with increased body temperature or after a viral infection.

Early symptoms

Common early symptoms of MS include:

- Muscle or motor symptoms, such as weakness, leg dragging, stiffness, a tendency to drop things, a feeling of heaviness, clumsiness, or a lack of coordination (ataxia).

- Visual symptoms, such as blurred, foggy, or hazy vision, eyeball pain (especially when you move your eyes), blindness, or double vision. Optic neuritis—sudden loss of vision that is often painful—is a fairly common first symptom. It occurs in up to 25 out of 100 people who have MS.

- Sensory symptoms, such as tingling, a pins-and-needles sensation, numbness, a band of tightness around the trunk or legs, or electrical sensations moving down the back and legs.

Advanced symptoms

As MS progresses, symptoms may become more severe and may include:

- Worse muscle problems, and stiff, mechanical movements (spasticity) or uncontrollable shaking (tremor). These problems may make walking difficult. A wheelchair may be needed some or all of the time.

- Pain and other sensory symptoms.

- Bladder symptoms, such as an inability to hold urine (urinary incontinence) or to completely empty the bladder, or a loss of bladder sensation.

- Constipation and other bowel disorders.

- Male erectile dysfunction (impotence) and female sexual dysfunction.

- Cognitive and emotional problems. These are common in people who have had MS for some time.

- Feeling very tired (fatigue). This can be worse if symptoms such as pain, spasticity, bladder problems, anxiety, or depression make it hard to sleep.

What Happens

In general, multiple sclerosis follows one of four courses:

- Relapsing-remitting, where symptoms may fade and then recur at random for many years. The disease doesn’t advance during the remissions. Most people who develop MS have a relapsing-remitting course. In 8 to 9 out of 10 people with this course of MS, the relapsing-remitting phase lasts about 20 years.footnote 1

- Secondary progressive, which at first follows a relapsing-remitting course. Later on, it becomes steadily progressive.

- Primary progressive, where the disease is progressive from the start.

- Progressive relapsing, where steady deterioration of nerve function begins when symptoms first appear. Symptoms appear and disappear, but nerve damage continues. Few people have this course of MS.

MS is different for every person. You may go through life with only minor problems. Or you may become seriously disabled. Most people are somewhere in between.

The duration of the disease varies. Most people who get MS live with it for decades.

Progress of MS

MS usually progresses with a series of relapses that occur over many years (relapsing-remitting MS). In many people the first MS attack involves just a single symptom. It may be weeks, months, or years before you have a relapse.

As time goes by, symptoms may linger after each relapse so you lose the ability to fully recover from the relapse. New symptoms often develop as the disease damages other areas of the brain or spinal cord.

Events that can mean you may have a more severe type of MS include:

- Frequent relapses during the first few years of the disease.

- Incomplete recovery between attacks.

- Early, lasting motor problems that affect movement.

- Many lesions that show up on an MRI early in the disease.

Some people have a few mild attacks from which they recover entirely. This is called benign MS.

Although rare, a small number of people die within several years of the onset of MS. This is called malignant or fulminant MS.

Because MS may affect your ability to move and walk, it can place limits on your daily living, particularly as you age. If you or someone in your family has MS, talk to your doctor about how MS may affect daily living. Knowing what to expect will help you plan for the future.

Complications of MS

Complications that may result from MS include:

- Urinary tract infections (UTIs).

- Constipation.

- Pressure injuries.

- Reduced ability to move and walk. This makes it necessary to use a wheelchair some or all of the time.

What Increases Your Risk

Your risk for multiple sclerosis (MS) increases with:

- Geographic location, or where you lived during childhood (up to age 15). People who spend the first 15 years of their lives in colder climates that are farther away from the equator tend to be more likely to get MS than people who lived closer to the equator during those years.

- Family history of MS. About 15 out of 100 people who have MS have a relative with MS, most often a brother or sister.footnote 2

- Certain genetic characteristics associated with the immune system. These appear more frequently in people who have MS. This may mean that there are one or more genes that may increase the chance of getting MS.

- Race. People of Western European ancestry are more likely to get MS.

- Being female. MS is about 3 times as common in women as in men.

When should you call your doctor?

Some of the symptoms of multiple sclerosis (MS) are similar to those of many other illnesses. See your doctor if over a period of time you have more than one symptom, such as:

- Blurry, foggy, or hazy vision, eyeball pain, loss of vision, or double vision.

- A feeling of heaviness or weakness, involuntary leg dragging, stiffness, walking problems, and clumsiness.

- Tingling or a pins-and-needles sensation; numbness; tightness in a band around the trunk, arms, or legs; or electric shock sensations moving down the back, arms, or legs.

- Inability to hold urine or to completely empty the bladder.

- Dizziness and unsteadiness.

- Problems with memory, attention span, finding the right words for what you mean, and daily problem-solving.

If you have been diagnosed with MS, see your doctor if:

- Your attacks become more frequent or severe.

- You begin having a symptom that you have not had before or you notice a significant change in symptoms that are already present.

Watchful waiting

Milder MS-type symptoms can be caused by many other conditions or may occur now and then in healthy people. For example, lots of people have minor numbness in their fingers or a mild dizzy spell once in a while. Stiffness and muscle weakness can result from being more active than usual. A wait-and-see approach (watchful waiting) is appropriate for these types of everyday aches and pains, so long as they do not continue.

If your symptoms occur more often or don’t go away, talk to your doctor.

For people with MS

Talk to your doctor about what to expect from the disease and from treatment. MS is an unpredictable disease, but you probably can get some idea of what is “normal” and what symptoms or problems are reasons for concern.

Some people who have MS want active, regular support from their doctors. Others want to manage their condition on their own as much as possible. Wherever you are in this range, find out which signs or symptoms mean that you need to see your doctor. And seek help when you need it.

Who to see

Health professionals who may be involved in evaluating symptoms of MS and treating the condition include:

- Family doctors or internists. Consult your doctor when symptoms first start. He or she will refer you to a neurologist if needed. If you have MS, your family doctor or internist can treat your general health problems even if you see a neurologist for MS treatment.

- Neurologists. A neurologist can decide whether your symptoms are caused by MS. He or she can also help you decide what may be the best treatment for your condition.

Many university medical centers and large hospitals have MS clinics or centers staffed by neurologists and other health professionals who specialize in diagnosing and treating MS. They may be able to provide the most thorough evaluation.

If you have been diagnosed with MS, at some point you may need to seek the help of:

- A physical therapist, to assist with exercise to maintain body strength and flexibility and deal with movement problems.

- An occupational therapist, to identify ways of accomplishing daily activities if MS has caused any physical limitations.

- A speech-language pathologist, to improve speech, chewing, and breathing if MS has affected the muscles of the face and throat.

- A physiatrist, to help with managing pain, maintaining strength, and adapting to physical disability.

- A psychologist or psychiatrist, to evaluate and treat depression, anxiety or other mood disorders, and problems with memory and concentration if these develop.

- A pain management specialist, to help with any significant chronic pain that MS may cause. A pain specialist, often as part of a pain clinic, can help find ways of reducing pain when possible and dealing with pain that doesn’t go away.

- A neurosurgeon, to do surgery for severe tremors or spasticity.

Exams and Tests

Diagnosing multiple sclerosis (MS) isn’t always easy and in some cases may take time.

Your medical history and neurological exam can identify possible nervous system problems and are often enough to strongly suggest a diagnosis of MS. Tests may help confirm or rule out the diagnosis when your history and exam do not provide clear evidence of the disease. MRI and neurological exam may help doctors predict which people will develop MS after a first attack of symptoms.

Tests to diagnose MS

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spinal cord. This test is done to confirm a diagnosis of MS.

- Lumbar puncture (sometimes called a spinal tap). This test may be done to evaluate cerebrospinal fluid. Most people with MS have abnormal results on this test.

- Evoked potential testing. This test can often reveal abnormalities in the brain and spinal cord and in the optic nerves of the eyes that other tests may not detect.

Confirming the diagnosis

MS is diagnosed when it is clear from neurological tests and a neurological exam that lesions (damaged areas) are present in more than one area of the central nervous system (usually the brain, spinal cord, or the nerves to the eyes). Tests will also clearly show that damage has occurred at more than one point in time.

Some people have had only one episode of a neurological symptom such as optic neuritis, but MRI tests suggest they may have MS. This is known as a clinically isolated syndrome. Many of these people go on to develop MS over time.

Tests to diagnose other health problems

Urinary tract tests may be needed to help diagnose a problem with bladder control in a person who has MS.

Neuropsychological tests may be needed to identify thinking or emotional problems, which may be present without the person being aware of them. Typically, these tests are in a question-and-answer format.

A blood test for JC virus antibodies may be done. This test can help you and your doctor understand your risk for getting a rare but serious brain infection called PML (progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy).

Treatment Overview

Treatment can make living with multiple sclerosis (MS) easier. Your type of treatment will depend on how severe your symptoms are and whether your disease is active or in remission. You may get medicines, physical therapy, and other treatment at home.

Medicines

Medicines are used to treat relapses, control the course of the disease (disease-modifying drugs or DMDs), or treat symptoms.

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society recommends that people with a definite diagnosis of MS and who have active, relapsing disease start treatment with medicines. This group also recommends treatment with medicine after the first attack in some people who are at a high risk for MS.footnote 3

If you decide not to try medicines at this time, meet with your doctor regularly to check whether the disease is progressing.

Ongoing monitoring

You and your doctor will set up a schedule of periodic appointments to monitor and treat your symptoms and follow the progress of your MS. Monitoring your condition helps your doctor find out if you may need to try a different treatment.

Home treatment

Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and nonmedical treatment done at home may also help you manage symptoms and adjust to living and working situations. To learn more, see Home Treatment.

End-of-life issues

In rare cases, MS is life-threatening. If your condition gets considerably worse, you may want to make a living will, which allows your wishes to be carried out if you are not able to make decisions for yourself. For more information, see the topic Care at the End of Life.

Prevention

In general, there is no way to prevent multiple sclerosis (MS) or its attacks. For people with relapsing-remitting MS, primary progressive MS, and secondary progressive MS, treatment with medicine may reduce the frequency of relapses and delay disability.

Home Treatment

If you have multiple sclerosis (MS), it is important to find ways of coping with the practical and emotional demands of the disease. These are different for everyone, so home treatment varies from person to person.

Home treatment may involve making it easier to get around your home, dealing with depression, handling specific symptoms, and getting support from your family and friends.

- Modify your home to keep it safe and easy to get around. For example, to help prevent falls, install grab bars in the bathroom and don’t use throw rugs. And try adjusting your daily schedule so that your routine is less stressful or tiring.

- Be active, either on your own or with the help of a physical therapist.

- Get help with urination problems. At some time, most people with MS have bladder problems. Your doctor may prescribe a medicine to help you.

- Avoid getting overheated. Increased body temperature can temporarily make your symptoms worse. Use an air conditioner, keep your home somewhat cool, and avoid hot swimming pools and hot tubs. During warm or hot weather, exercise in an air-conditioned area rather than outdoors.

- Eat plenty of fruits, vegetables, grains, cereals, legumes, poultry, fish, lean meats, and low-fat dairy products. A balanced diet for a person who has MS is the same as that recommended for most healthy adults.

- Change how and what you eat if you are having problems swallowing.

- Thicker drinks make swallowing easier. Try milk shakes or juices in gelatin form.

- Avoid foods such as crackers or cakes that crumble easily. These can cause choking.

- Soft foods need less chewing. Use a blender to prepare food for easiest chewing.

- Eat frequent, small meals to avoid fatigue from eating heavy meals.

Ask your doctor about physical therapy and occupational therapy to help you manage at work and home.

Make all efforts to preserve your health. Proper diet, rest, wise use of energy, and practical and emotional support from your family, friends, and doctor can all be very helpful.

For more advice about coping with MS at home, contact the National Multiple Sclerosis Society at www.nationalmssociety.org.

Medications

Medicines for multiple sclerosis (MS) may be used:

- During a relapse, to make the attack shorter and less severe.

- Over a long period of time, to alter the natural course of the disease (disease-modifying drugs or DMDs).

- To control specific symptoms as they occur.

Controlling a relapse

These medicines can shorten a sudden relapse and help you feel better sooner. They have not been shown to affect the long-term course of the disease or to prevent disability.

- Corticosteroids (such as methylprednisolone)

- ACTH (adrenocorticotropic hormone)

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG)

- Plasma exchange

Disease-modifying treatment

Strong evidence suggests that MS is caused by the immune system causing inflammation and attacking nerve cells and myelin, which is the protective coating surrounding the nerve fibers. Medicines that change the way the immune system works can reduce the number and severity of attacks that damage the nerves and myelin.

For people who have relapsing-remitting MS, disease-modifying therapy can reduce the number and severity of relapses. It may also delay disability in some people. Some of these medicines may also delay disease progression and reduce relapses in some people who have primary progressive MS or secondary progressive MS.

The most commonly used disease-modifying therapies are:

- Interferon beta (such as Betaseron), for clinically isolated syndrome (first MS attack), relapsing-remitting MS, and secondary progressive MS.

- Glatiramer (Copaxone), for clinically isolated syndrome and relapsing-remitting MS.

Other disease-modifying medicines may also be used for MS. Your doctor will prescribe a medicine depending on the type of MS you have, your symptoms, and how your body responds. They include:

- Alemtuzumab (Campath).

- Dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera).

- Fingolimod (Gilenya).

- Mitoxantrone (Novantrone).

- Natalizumab (Tysabri).

- Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus).

- Teriflunomide (Aubagio).

Some people have only one episode of a neurological symptom such as optic neuritis. Yet MRI or other tests suggest that these people have MS. This is known as a clinically isolated syndrome. Many of these people go on to develop MS over time. In most cases, doctors will prescribe medicine for people who have had a clinically isolated syndrome. These medicines, when taken early or even before you have been diagnosed with MS, may keep the disease from getting worse or extend your time without disease.footnote 3

Relieving symptoms

Treating specific symptoms can be effective, even if it doesn’t stop the progression of the disease. Symptoms that can often be controlled or relieved with medicine include:

- Fatigue.

- Muscle stiffness (spasticity).

- Urinary problems.

- Constipation.

- Pain and abnormal sensations.

- Depression.

Medicines can also help with sexual problems, emotional problems, and walking problems. Sildenafil (Viagra) can help with sexual problems in both men and women. Clomipramine may also be given to improve erectile dysfunction. Dextromethorphan and quinidine (Nuedexta) is a medicine that can be used for uncontrollable outbursts of crying or laughing at strange or inappropriate times. Dalfampridine (Ampyra) is a medicine that can be used to help with walking problems.

Medicine may be used only some of the time or regularly, depending on how severe or constant a certain symptom is. Changes in diet, schedule, exercise, and other habits can also help manage some of these symptoms. See Home Treatment.

Cannabinoids are substances found in marijuana. Similar drugs can be created in a lab. Some forms of natural and man-made cannabinoids may help with symptoms such as pain and spasticity. They are not available in all areas. Talk to your doctor if you are considering cannabinoids.

Medicines being studied

A variety of other medicines and biological chemicals have been tried or are being studied as therapy for MS. None of them have been clearly proved as beneficial, and none have been approved for treatment of MS.

Several medicines are being tested in clinical trials. People with MS who have not responded to standard therapy sometimes choose to take part in these trials. To learn more about clinical trials, talk to your doctor or contact the National Multiple Sclerosis Society at www.nationalmssociety.org.

Deciding about disease-modifying therapy

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society recommends that people with a definite diagnosis of MS and active, relapsing disease start treatment with interferon beta or glatiramer. Most neurologists support this recommendation and now agree that permanent damage to the nervous system may occur early on, even while symptoms are still quite mild. Early treatment may help prevent or delay some of this damage. In general, treatment is recommended until it no longer provides a clear benefit.

The National MS Society also says that treatment with medicine may be considered after the first attack in some people who are at a high risk for MS (before MS is definitely diagnosed).

Despite the recommendation, some people find it hard to decide whether to begin disease-modifying therapy, especially when their symptoms have been fairly mild. Some may not want to bear the risks and side effects of medicine when they are not sure they need it. Some may want to see whether their disease gets worse before they start therapy. A small percentage of people diagnosed with MS may never have more than a few mild episodes and may never develop any disability, but the disease is unpredictable.

Insurance may not cover all types of treatment.

Treating symptoms and relapses

The need and desire for medicine vary. If your symptoms are mild, you may choose to manage them without any medicine. If you have specific symptoms that are causing problems, certain medicines may help you keep them under control. Or you may want to use medicine only during a relapse.

You may also want to think about:

- The possible side effects of using steroids or other medicines to treat symptoms or control a relapse. Some people have only minor side effects. But others may have side effects that concern them more than their MS symptoms.

- The costs of treating symptoms and controlling relapses. In some cases, using medicine to control symptoms and relapses may reduce the need for hospital stays.

- Other personal issues that you face at work or at home.

Also keep in mind that it can be hard to tell if medicine is helping. Multiple sclerosis is a disease with spontaneous remissions. This means that your condition can improve on its own, without any treatment. Just because your symptoms improve after treatment doesn’t mean that a treatment is working.

Surgery

People with multiple sclerosis (MS) who have severe tremor (shakiness) affecting movement may be helped by surgery. People with severe spasticity (muscle stiffness) may be helped by insertion of a spinal pump to deliver medicines when oral medicines fail.

Surgery choices

Surgery options include:

- Deep brain stimulation for tremor. This treatment is only considered after other options have failed. Severe and disabling tremor that occurs with the slightest movement of the limbs may be helped by an implanted device that stimulates an area of the brain. A neurological surgeon does the surgery to implant the device.

- Implantation of a drug catheter or pump, for spasticity. This treatment is only considered after other options have failed. People who have severe pain or spasticity may benefit from having a catheter or pump placed in the lower spinal area to deliver a constant flow of medicine, such as baclofen.

Other Treatment

The unpredictability and variety of symptoms caused by multiple sclerosis (MS) make it a disease that people have tried to treat in many different ways.

Complementary therapies

Many complementary therapies have been proposed as treatments for MS. None of these treatments have been shown to modify the course of the disease. Some of those most commonly used are:

- Acupuncture.

- Biofeedback.

- Diets and vitamin, mineral, herbal, or dietary supplements.

- Massage therapy(often used by physical therapists).

- Meditation.

- Yoga.

Although clinical research has not shown all of these complementary therapies to be effective, a person with MS may benefit from safe nontraditional therapies along with conventional medical treatment. Some complementary therapies may help relieve stress, depression, fatigue, and muscle tension. And some may improve your overall well-being and quality of life. Talk to your doctor if you are interested in trying any of these complementary therapies or alternative medical approaches to MS treatment.

Clinical research also has been unable to show that treatments such as “liberation” angioplasty for chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency (CCSVI), bee venom therapy, Prokarin (a caffeine and histamine combination), removal of mercury fillings (dental amalgams), and hyperbaric oxygen therapy have any benefits for people who have MS. Some of these therapies may be harmful as well as expensive and are not recommended by most experts.

Experimental medical treatments

Experimental treatments for MS involve reducing the activity of the immune system. This may be done with medicines and biological chemicals or through methods such as total lymphoid irradiation, in which the entire lymph node system is exposed to radiation. While these methods have been used with success in the treatment of certain other medical conditions, they have failed to produce significant benefits when tested in controlled clinical trials. They remain experimental treatments for MS.

Stem cell transplant, which uses immature cells from the bone marrow, has been studied. Early results suggest that stem cell transplant may delay disability, especially in people with relapsing-remitting MS.footnote 4 Stem cell transplant may be an option for people who have very aggressive or malignant forms of MS.footnote 5 It remains unproved and isn’t recommended for treating relapsing-remitting MS.

What to think about

There is no cure for MS. So far, the only treatments proved to affect the course of the disease are approved disease-modifying therapies. Other types of treatment should not replace these medicines if you are a candidate for treatment with them.

Some people who have MS report that complementary therapies have worked for them. This may be in part because of the placebo effect. Some complementary therapies don’t treat the disease itself, but they may affect a person’s sense of well-being and help the person feel better and healthier.

If you are thinking about trying a complementary treatment, get the facts first. Discuss these questions with your doctor:

- Is it safe? Talk with your doctor about the safety and potential side effects of the treatment. This is especially important if you are on drug therapy for MS. Some complementary treatments in combination with drug therapy can be quite dangerous. A treatment that could be harmful to you and may or may not improve your symptoms isn’t worth the risk.

- Does it work? Because MS symptoms can come and go, you may find it hard to judge whether a particular treatment is really working. Keep in mind that if you get better after using a certain treatment, the treatment isn’t always the reason for the improvement. MS may often improve on its own (spontaneous remission).

- How much does it cost? An expensive, unproven treatment that may or may not help you may not be worth its cost. Beware of therapy providers or products that require a large financial investment at the beginning of a series of treatments.

- Will it improve my general health? Even if they aren’t effective in treating MS, some complementary practices (such as acupuncture, massage, or yoga) may be safe. And they may lead to healthy habits that improve your overall well-being. These might be worth trying.

With a hard-to-treat disease like MS, it can be tempting to jump at the promise of an effective treatment. Be cautious about trying unproven treatments.

References

Citations

- Tremlett H, et al. (2010). New perspectives in the natural history of multiple sclerosis. Neurology, 74(24): 2004–2015.

- Ropper AH, et al. (2014). Multiple sclerosis and other inflammatory demyelinating diseases. In Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 10th ed., pp. 1060–1131. New York: McGraw-Hill Education.

- National Clinical Advisory Board of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (2008). Disease Management Consensus Statement. New York: National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Available online: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/for-professionals/healthcare-professionals/publications/expert-opinion-papers/index.aspx.

- Burt RK, et al. (2009). Autologous non-myeloablative haemopoietic stem cell transplantation in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A phase I/II study. Lancet Neurology, 8(3): 244–253.

- Fassas A, et al. (2011). Long-term results of stem cell transplantation for MS: A single-center experience. Neurology, 76(12): 1066–1070.

Other Works Consulted

- Burton JM, et al. (2009). Oral versus intravenous steroids for treatment of relapses in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3).

- Cortese I, et al. (2011). Evidence-based guideline update: Plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 76(3): 294–300.

- Courtney AM, et al. (2009). Multiple sclerosis. Medical Clinics of North America, 93(2): 451–476.

- Fox RJ, Arnold DL (2009). Seeing injectable MS therapies differently: They are more similar than different. Neurology, 72(23): 1972–1973.

- Giesser B (2010). Reproductive Issues in Persons With Multiple Sclerosis. Clinical Bulletin: Information Health Professionals. Available online: http://www.nationalmssociety.org/for-professionals/healthcare-professionals/publications/clinical-bulletins/index.aspx.

- Goodin DS, et al. (2008, reaffirmed 2010). Neutralizing antibodies to interferon beta: Assessment of their clinical and radiographic impact: An evidence report: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 68(13): 977–984.

- Grossman P, et al. (2010). MS quality of life, depression, and fatigue improve after mindfulness training: A randomized trial. Neurology, 75(13): 1141–1149.

- Kelly VM, et al. (2009). Obstetric outcomes in women with multiple sclerosis and epilepsy. Neurology, 73(22): 1831–1836.

- Koppel B, et al. (2014). Systematic review: Efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic conditions. Neurology, 82(17): 1556–1563. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363. Accessed January 12, 2016.

- Marriott JJ, et al. (2010). Evidence report: The efficacy and safety of mitoxantrone (Novantrone) in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: Report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 74(18): 1463–1470.

- McDonald WI, et al. (2001). Recommended diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: Guidelines from the International Panel on the Diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis. Annals of Neurology, 50(1): 121–127.

- Polman CH, et al. (2005). Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the McDonald Criteria. Annals of Neurology, 58(6): 840–846.

- Polman CH, et al. (2006). A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(9): 899–910.

- Polman CH, et al. (2011). Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Annals of Neurology, 69(2): 292–302.

- Spelman T, et al. (2014). Seasonal variation of relapse rate in multiple sclerosis is latitude dependent. Annals of Neurology, published online October 4, 2014. DOI: 10.1002/ana.24287. Accessed October 31, 2014.

- Yadav V, et al. (2014). Summary of evidence-based guideline: Complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 82(12): 1083–1092.

- Yousry TA, et al. (2006). Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. New England Journal of Medicine, 354(9): 924–933.

Current as of: March 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Anne C. Poinier, MD – Internal Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Karin M. Lindholm, DO – Neurology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.