Shingles

Topic Overview

What is shingles?

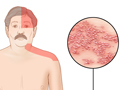

Shingles is a painful skin rash. It is caused by the varicella zoster virus. Shingles usually appears in a band, a strip, or a small area on one side of the face or body. It is also called herpes zoster.

Shingles is most common in older adults and people who have weak immune systems because of stress, injury, certain medicines, or other reasons. Most people who get shingles will get better and will not get it again. But it is possible to get shingles more than once.

What causes shingles?

Shingles occurs when the virus that causes chickenpox starts up again in your body. After you get better from chickenpox, the virus “sleeps” (is dormant) in your nerve roots. In some people, it stays dormant forever. In others, the virus “wakes up” when disease, stress, or aging weakens the immune system. Some medicines may trigger the virus to wake up and cause a shingles rash. It is not clear why this happens. But after the virus becomes active again, it can only cause shingles, not chickenpox.

You can’t catch shingles from someone else who has shingles. But there is a small chance that a person with a shingles rash can spread the virus to another person who hasn’t had chickenpox and who hasn’t gotten the chickenpox vaccine.

What are the symptoms?

Shingles symptoms happen in stages. At first you may have a headache or be sensitive to light. You may also feel like you have the flu but not have a fever.

Later, you may feel itching, tingling, or pain in a certain area. That’s where a band, strip, or small area of rash may occur a few days later. The rash turns into clusters of blisters. The blisters fill with fluid and then crust over. It takes 2 to 4 weeks for the blisters to heal, and they may leave scars. Some people only get a mild rash. And some do not get a rash at all.

It’s possible that you could also feel dizzy or weak. Or you could have pain or a rash on your face, changes in your vision, changes in how well you can think, or a rash that spreads. A rash or blisters on your face, especially near an eye or on the tip of your nose, can be a warning of eye problems.

Call your doctor now if you think you may have shingles. It’s best to get early treatment. Medicine can help your symptoms get better sooner. And if you have shingles near your eye or nose, see your doctor right away. Shingles that gets into the eye can cause permanent eye damage.

How is shingles treated?

Shingles is treated with medicines. These medicines include antiviral medicines and medicines for pain.

See your doctor right away if you think you may have shingles. Starting antiviral medicine right away can help your rash heal faster and be less painful. And you may need prescription pain medicine if your case of shingles is very painful.

Good home care also can help you feel better faster. Take care of skin sores, and keep them clean. Take your medicines as directed. If you are bothered by pain, tell your doctor. Other treatments may help with intense pain.

Who gets shingles?

Anyone who has had chickenpox can get shingles. You have a greater chance of getting shingles if you are older than 50 or if you have a weak immune system.

There is a shingles vaccine for adults. It lowers your chances of getting shingles and prevents long-term pain that can occur after shingles. And if you do get shingles, having the vaccine makes it more likely that you will have less pain and your rash will clear up more quickly.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Shingles is a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus, a type of herpes virus that causes chickenpox. After you have had chickenpox, the virus lies inactive in your nerve roots and remains inactive until, in some people, it flares up again. If the virus becomes active again, you may get a rash that occurs only in the area of the affected nerve. This rash is called shingles.

Anyone who has had even a mild case of chickenpox can get shingles. This includes children.

Transmission

Exposure to shingles will not cause you to get shingles. But if you have not had chickenpox and have not gotten the chickenpox vaccine, you can get chickenpox if you are exposed to shingles. Someone who has shingles can expose you to the virus if you come into contact with the fluid in the shingles blisters.

If you are having an active outbreak of shingles, you can help prevent the spread of the virus to other people. Cover any fluid-filled blisters that are on a part of your body that isn’t covered with clothes. Choose a type of dressing that absorbs fluid and protects the sores.

Symptoms

When the virus that causes chickenpox reactivates, it causes shingles. Early symptoms of shingles include headache, sensitivity to light, and flu-like symptoms without a fever. You may then feel itching, tingling, or pain where a band, strip, or small area of rash may appear several days or weeks later. A rash can appear anywhere on the body but will be on only one side of the body, the left or right. The rash will first form blisters, then scab over, and finally clear up over a few weeks. This band of pain and rash is the clearest sign of shingles.

The rash caused by shingles is more painful than itchy. The nerve roots that supply sensation to your skin run in pathways on each side of your body. When the virus becomes reactivated, it travels up the nerve roots to the area of skin supplied by those specific nerve roots. This is why the rash can wrap around either the left or right side of your body, usually from the middle of your back toward your chest. It can also appear on your face around one eye. It is possible to have more than one area of rash on your body.

Shingles develops in stages:

Prodromal stage (before the rash appears)

- Pain, burning, tickling, tingling, and/or numbness occurs in the area around the affected nerves several days or weeks before a rash appears. The discomfort usually occurs on the chest or back, but it may occur on the belly, head, face, neck, or one arm or leg.

- Flu-like symptoms (usually without a fever), such as chills, stomachache, or diarrhea, may develop just before or along with the start of the rash.

- Swelling and tenderness of the lymph nodes may occur.

Active stage (rash and blisters appear)

- A band, strip, or small area of rash appears. It can appear anywhere on the body but will be on only one side of the body, the left or right. Blisters will form. Fluid inside the blisters is clear at first but may become cloudy after 3 to 4 days. A few people won’t get a rash, or the rash will be mild.

- A rash may occur on the forehead, cheek, nose, and around one eye (herpes zoster ophthalmicus), which may threaten your sight unless you get prompt treatment.

- Pain, described as “piercing needles in the skin,” may occur along with the skin rash.

- Blisters may break open, ooze, and crust over in about 5 days. The rash heals in about 2 to 4 weeks, although some scars may remain.

Postherpetic neuralgia (chronic pain stage)

- Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is the most common complication of shingles. It lasts for at least 30 days and may continue for months or years. Symptoms are:

- Aching, burning, stabbing pain in the area of the earlier shingles rash.

- Persistent pain that may linger for years.

- Extreme sensitivity to touch.

- The pain associated with PHN most commonly affects the forehead or chest. This pain may make it difficult for the person to eat, sleep, and do daily activities. It may also lead to depression.

Shingles may be confused with other conditions that cause similar symptoms. The rash from shingles may be mistaken for an infection from herpes simplex virus (HSV), poison oak or ivy, impetigo, or scabies. The pain from PHN may feel like appendicitis, a heart attack, ulcers, or migraine headaches.

What Happens

Shingles is caused by the same virus that causes chickenpox. After an attack of chickenpox, the virus remains in the tissues in your nerves. As you get older, or if you have an illness or stress that weakens your immune system, the virus may reappear in the form of shingles.

You may first have a headache, flu-like symptoms (usually without a fever), and sensitivity to light, followed by itching, tingling, or pain in the area where a rash may develop. The pain usually occurs several days or weeks before a rash appears on the left or right side of your body. The rash will be in a band, a strip, or a small area. In 3 to 5 days, the rash turns into fluid-filled blisters that ooze and crust over. The rash heals in about 2 to 4 weeks, although you may have long-lasting scars. A few people won’t get a rash, or the rash will be mild.

Most people who get shingles will not get the disease again.

Complications of shingles

Delaying or not getting medical treatment may increase your risk for complications. Complications of shingles include:

- Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), which is pain that does not go away within 1 month. It may last for months or even years after shingles heals. It is more common in people age 50 and older and in people who have a weakened immune system due to another disease, such as diabetes or HIV infection.

- Disseminated zoster, which is a blistery rash that spreads over a large portion of the body and can affect the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, joints, and intestinal tract. Infection may spread to nerves that control movement, which may cause temporary weakness.

- Cranial nerve complications. If shingles affects the nerves originating in the brain (cranial nerves), complications may include:

- Inflammation, pain, and loss of feeling in one or both eyes. The infection may threaten your vision. A rash may appear on the side and tip of the nose (Hutchinson’s sign).

- Intense ear pain, a rash around the ear, mouth, face, neck, and scalp, and loss of movement in facial nerves (Ramsay Hunt syndrome). Other symptoms may include hearing loss, dizziness, and ringing in the ears. Loss of taste and dry mouth and eyes may also occur.

- Inflammation, and possibly blockage, of blood vessels, which may lead to stroke.

- Scarring and skin discoloration.

- Bacterial infection of the blisters.

- Muscle weakness in the area of the infected skin before, during, or after the episode of shingles.

What Increases Your Risk

Things that increase risk for shingles include:

- Having had chickenpox. You must have had chickenpox to get shingles.

- Being older than 50.

- Having a weakened immune system due to another disease, such as diabetes or HIV infection.

- Experiencing stress or trauma.

- Having cancer or receiving treatment for cancer.

- Taking medicines that affect your immune system, such as steroids or medicines that are taken after having an organ transplant.

If a pregnant woman gets chickenpox, her baby has a high risk for shingles during his or her first 2 years of life. And if a baby gets chickenpox in the first year of life, he or she has a higher risk for shingles during childhood.footnote 1

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is a common complication of shingles that lasts for at least 30 days and may continue for months or years. You can reduce your risk for getting shingles and developing PHN by getting the shingles vaccine.

When should you call your doctor?

If you think you have shingles, see a doctor as soon as possible. Early treatment with antiviral medicines may help reduce pain and prevent complications of shingles, such as disseminated zoster or postherpetic neuralgia.

A rash or blisters on your face, especially near an eye or on the tip of your nose, can be a warning of eye problems. Treatment can help prevent permanent eye damage.

If you still feel intense pain for more than 1 month after the skin heals, see your doctor to find out whether you have postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). Getting your pain under control right away may prevent nerve damage that may cause pain that lasts for months or years.

Who to see

- Family medicine physician

- Internist

- Dermatologist

- Physician assistant

- Nurse practitioner

- Neurologist, for central nervous system complications of shingles

Exams and Tests

Doctors can usually identify shingles when they see an area of rash around the left or right side of your body. If a diagnosis of shingles is not clear, your doctor may order lab tests, most commonly herpes tests, on cells taken from a blister.

If there is reason to think that shingles is present, your doctor may not wait to do tests before treating you with antiviral medicines. Early treatment may help shorten the length of the illness and prevent complications such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Treatment Overview

There is no cure for shingles, but treatment may shorten the length of illness and prevent complications. Treatment options include:

- Antiviral medicines to reduce the pain and duration of shingles.

- Pain medicines, antidepressants, and topical creams to relieve long-term pain.

Initial treatment

As soon as you are diagnosed with shingles, your doctor probably will start treatment with antiviral medicines. If you begin medicines within the first 3 days of seeing the shingles rash, you have a lower chance of having later problems, such as postherpetic neuralgia.

The most common treatments for shingles include:

- Antiviral medicines, such as acyclovir, famciclovir, or valacyclovir, to reduce the pain and the duration of shingles.

- Over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, to help reduce pain during an attack of shingles. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

- Topical antibiotics, applied directly to the skin, to stop infection of the blisters.

For severe cases of shingles, some doctors may have their patients use corticosteroids along with antiviral medicines. But corticosteroids are not used very often for shingles. This is because studies show that taking a corticosteroid along with an antiviral medicine doesn’t help any more than just taking an antiviral medicine by itself.footnote 2

Ongoing treatment

If you have pain that persists longer than a month after your shingles rash heals, your doctor may diagnose postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), the most common complication of shingles. PHN can cause pain for months or years. It affects 10 to 15 out of 100 people who have had shingles.footnote 3 Treatment to reduce the pain of postherpetic neuralgia includes:

- Antidepressant medicines, such as a tricyclic antidepressant (for example, amitriptyline).

- Topical anesthetics that include benzocaine, which are available in over-the-counter forms that you can apply directly to the skin for pain relief. Lidocaine patches, such as Lidoderm, are available only by prescription.

- Anticonvulsant medicines, such as gabapentin or pregabalin.

- Opioids, such as codeine.

- Other medicines that treat pain, such as gabapentin enacarbil (Horizant).

Topical creams containing capsaicin may provide some relief from pain. There is also a high-dose skin patch available by prescription (Qutenza) for postherpetic neuralgia. Capsaicin may irritate or burn the skin of some people, and it should be used with caution.

Treatment if the condition gets worse

In some cases, shingles causes long-term complications. Treatment depends on the specific complication.

- Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is persistent pain that lasts months or even years after the shingles rash heals. Certain medicines, such as anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and opioids, can relieve pain. Most cases of PHN resolve within a year.

- Disseminated zoster is a blistery rash over a large portion of the body. It may affect the heart, lungs, liver, pancreas, joints, and intestinal tract. Treatment may include both antiviral medicines to prevent the virus from multiplying and antibiotics to stop infection.

- Herpes zoster ophthalmicus is a rash on the forehead, cheek, nose, and around one eye, which could threaten your sight. You should seek prompt treatment from an ophthalmologist for this condition. Treatment may include rest, cool compresses, and antiviral medicines.

- If the shingles virus affects the nerves originating in the brain (cranial nerves), serious complications involving the face, eyes, nose, and brain can occur. Treatment depends on the nature and location of the complication.

Prevention

Anyone who has had chickenpox may get shingles later in life. But there are two types of vaccines, Shingrix (RZV) and Zostavax (ZVL), that may help prevent shingles or make it less painful if you do get it.

Two doses of RZV are recommended for adults ages 50 and older, whether or not they’ve had shingles before. It is also recommended for adults who have already had the ZVL vaccine.

ZVL is available for adults ages 60 and older. This vaccine is given as one dose. You can ask your doctor or pharmacist which vaccine is right for you.

If you have never had chickenpox, you may avoid getting the virus that causes both chickenpox and later shingles by receiving the varicella vaccine.

If you have never had chickenpox and have never gotten the chickenpox vaccine, avoid contact with people who have shingles or chickenpox. Fluid from shingles blisters is contagious and can cause chickenpox (but not shingles) in people who have never had chickenpox and who have never gotten the chickenpox vaccine.

If you have shingles, avoid close contact with people until after the rash blisters heal. It is especially important to avoid contact with people who are at special risk from chickenpox, such as:

- Pregnant women, infants, children, or anyone who has never had chickenpox.

- Anyone who is currently ill.

- Anyone with a weak immune system who is unable to fight infection (such as someone with HIV infection or diabetes).

If you cover the shingles sores with a type of dressing that absorbs fluid and protects the sores, you can help prevent the spread of the virus to other people.

Home Treatment

You may reduce the duration and pain of shingles by:

- Taking good care of skin sores.

- Avoid picking at and scratching blisters. If left alone, blisters will crust over and fall off naturally.

- Use cool, moist compresses if they help ease discomfort. Lotions, such as calamine, may be applied after wet compresses.

- Apply cornstarch or baking soda to help dry the sores so that they heal more quickly.

- Soak crusted sores with tap water or Burow’s solution to help clean away crusts, decrease oozing, and dry and soothe the skin.

- Ask your doctor about using topical creams to help relieve the inflammation caused by shingles.

- If your skin becomes infected, ask your doctor about prescription antibiotic creams or ointments.

- Using medicines as prescribed to treat shingles or postherpetic neuralgia, which is pain that lasts for at least 30 days after the shingles rash heals.

- Using nonprescription pain medicines, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, to help reduce pain during an attack of shingles or pain caused by postherpetic neuralgia. If you are already taking a prescription pain medicine, talk with your doctor before using any over-the-counter pain medicine. Some prescription pain medicines have acetaminophen (Tylenol), and getting too much acetaminophen can be harmful. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

If home treatment doesn’t help with pain, talk with your doctor. Getting your pain under control right away may prevent nerve damage that may cause pain that lasts for months or years.

Medications

Medicines can help limit the pain and discomfort caused by shingles, shorten the time you have symptoms, and prevent the spread of the disease. Medicines also may reduce your chances of developing shingles complications, such as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) or disseminated zoster.

Medicine choices

Medicines to treat shingles when the rash is present (active stage) may include:

- Over-the-counter pain medicines, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen, to help reduce pain. Be safe with medicines. Read and follow all instructions on the label.

- Antiviral medicines, to reduce the pain and duration of shingles.

- Topical antibiotics, which are applied directly to the skin, to stop infection of the blisters.

Medicines to treat postherpetic neuralgia pain may include:

- Tricyclic antidepressants, such as amitriptyline.

- Medicines put on the skin (topical medicines), such as creams or skin patches containing capsaicin or lidocaine.

- Anticonvulsants, such as gabapentin or pregabalin.

- Nerve block injections.

- Tramadol and other opioids, such as codeine, oxycodone, and morphine.

What to think about

For some people, nonprescription pain relievers (analgesics) are enough to help control pain caused by shingles or postherpetic neuralgia. But for others, stronger medicines may be needed. And if prescription medicines don’t help control your pain, you may need to see a pain specialist about other ways to treat PHN.

Other Treatment

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), the most common complication of shingles, is difficult to treat. Your doctor may recommend other treatments, along with medicines, to control the pain of PHN.

Other treatment choices

There are other treatments that may be used for shingles and postherpetic neuralgia. These treatments may help, but there is no clear evidence from studies that show how well these treatments work. These other treatments include:

- Acupuncture, a Chinese therapy that has been used for centuries to reduce pain.

- Biofeedback, a method of consciously controlling a body function that is normally regulated automatically by the body.

- Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), a therapy that uses mild electrical current to treat pain.

Psychological therapies that help you tolerate long-term pain, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, may be helpful. These methods can include counseling as well as learning techniques that teach you to shift your focus of attention away from the pain, such as relaxation and breathing exercises.

For severe pain from PHN, you may need to see a pain management specialist. These doctors are trained to help with pain that doesn’t respond to medicines or usual treatments.

References

Citations

- Gershon AA (2009). Varicella zoster virus. In RD Feigin et al., eds., Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 6th ed., vol. 2, pp. 2077–2088. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

- Chen N, et al. (2010). Corticosteroids for preventing postherpetic neuralgia (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (12).

- Dubinsky RM, et al. (2004, reaffirmed 2008). Practice parameter: Treatment of postherpetic neuralgia. An evidence-based report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology, 63(6): 959–965.

Other Works Consulted

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2008). Prevention of herpes zoster: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR, 57(05): 1–30. Also available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5705a1.htm. [Erratum in MMWR, 57(28): 779. Also available online: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5728a5.htm.]

- Habif TP (2010). Herpes zoster. In Clinical Dermatology, A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy, 5th ed., pp. 479–490. Philadelphia: Mosby.

- Herpes zoster vaccine (Zostavax) revisited (2010). Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics, 52(1339): 41.

- Wolff K, Johnson RA (2009). Varicella-zoster virus infections. In Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology, 6th ed., pp. 837–845. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical.

Current as of: June 9, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.