Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery: How It Is Done

Topic Overview

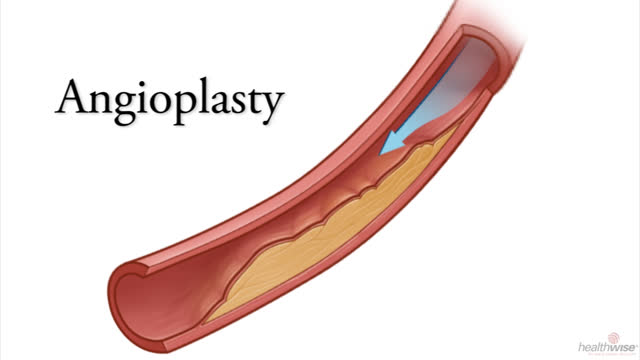

During coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, your surgeon will use a healthy blood vessel from another part of your body to create an alternate route, or bypass, around narrowed or blocked sections of your coronary arteries. This bypass surgery allows more blood to reach your heart muscle.

Your medical team will monitor your vital signs, such as blood pressure, heart rhythm, and blood oxygen levels.

Opening the chest

Your surgeon will make a cut, or incision, in the middle or side of your chest. He or she may cut through your breastbone and spread apart your rib cage. The rib cage is opened to expose all internal organs within your chest cavity (a process called a sternotomy). Your surgeon next cuts through the saclike lining that protects the heart (pericardium) to access the heart itself. Your coronary arteries lie on both the front and back surfaces of the heart.

Harvesting a vein to use as a graft blood vessel

The surgeon can remove a piece of healthy blood vessel from these places in the body:

- The inside of your leg

- Your forearm

- Just behind your chest wall

These blood vessels will be used as bypass grafts around narrowed or blocked portions of your coronary arteries.

Leg and arm. While your chest cavity is being opened, the surgeon’s assistant may begin to remove, or harvest, a healthy blood vessel from your arm (radial artery) or leg (saphenous vein).

Using a chest-wall artery for a graft vessel

Besides your saphenous vein and radial arteries, other blood vessels can be used as bypass grafts. In fact, given that they are located close to the heart and coronary arteries, the left and right internal mammary arteries (LIMA and RIMA) are actually favored by many doctors. These arteries have two distinct advantages besides their location:

- Mammary arteries are already attached to the main artery (the aorta). This means that only its other end must be disconnected and grafted onto the diseased coronary artery.

- Because they are arteries, the LIMA and RIMA are more accustomed to a forceful blood flow than a saphenous vein. (Veins carry blood from the body back to the heart and aren’t under as much pressure.) So the LIMA or RIMA may prove to be more durable in the years after your surgery.

Putting you on the heart-lung bypass machine

After your coronary arteries have been exposed and a usable blood vessel segment has been harvested, your surgical team may place you on a heart-lung bypass machine. Alternately, your surgical team may do the operation while your heart is beating. If you are placed on the heart-lung bypass machine, your heart will be temporarily stopped during the surgery so your surgeon can perform surgery on your coronary arteries. The heart-lung bypass machine does the work of your heart and lungs so that all the parts of your body still receive the oxygen-rich blood they need to survive.

While the ventilator physically inflates and deflates your lungs, the bypass machine performs the lungs’ main job of adding oxygen and removing unwanted gases from your blood. Also, the machine circulates that blood through your body.

After the heart-lung machine has been set up, the blood flowing from your heart to the rest of your body will be stopped by clamping the aorta and will be rerouted through the heart-lung bypass machine. The surgeon stops your heartbeat with a medicine. Your heart will not beat again until the new grafts have been put in place.

Bypassing your diseased coronary arteries

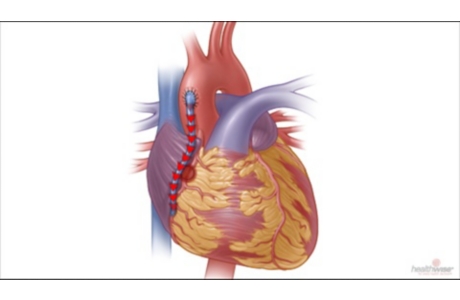

Your surgeon will start to operate on the coronary arteries. The harvested vein in the sterile saline solution is cut into appropriate lengths. Your surgeon will attach one end of the blood vessel to the aorta and the other end onto a portion of the coronary artery past the location in the artery where there is narrowing or blockage.

In the case of the LIMA or RIMA, one end remains attached to your chest wall and the other end is connected to the coronary artery. Regardless of which type of blood vessel is used, oxygen-rich blood is rerouted around the narrowed or blocked section of the coronary artery and into a healthy section where it can feed into the heart muscle.

Preventing blood loss during surgery

During the surgery, blood may spill into your chest cavity as small blood vessels are cut. To prevent this blood from interfering with surgery, a nurse or surgeon’s assistant will use a suction device (which looks like a large plastic straw) to suck up the blood. The blood is then recycled back to the body. Despite this effort, though, about half of the people who have CABG surgery end up needing a blood transfusion.

Restarting your heart

If you are on the heart-lung bypass machine, your doctor will restart your heart. After your bypass grafts have been sewn in place with strong stitches (sutures), your doctor will take the clamp off of your aorta. This will allow blood to flow to your heart, and the heart will typically start to beat again.

When your heart starts to beat again, you will be taken off the heart-lung bypass machine. Your surgeon may then apply a small electric shock, or your anesthesiologist may administer another medicine to help your heart muscle regain its natural rhythm.

Closing your chest cavity

Prior to closing up your sternum, your surgeon will place several small tubes inside your chest cavity, with one end exiting your body through an incision in your upper abdomen. These tubes allow drainage of any extra fluids from your chest. Your surgeon will then close your rib cage and use metal wires to bring the two halves of your sternum back together.

Finally, your surgeon will sew the soft tissues and muscles in your chest together with extra-strong stitches, or sutures. Surgery without complications usually takes 3 to 6 hours, depending on how many coronary arteries are bypassed.

Final thoughts

Although the CABG procedure is considered a relatively safe procedure, it also involves certain risks. It is important that you educate yourself about the risks of CABG surgery beforehand and talk with your surgeon about how your current health condition will affect your risk for complications.

References

Other Works Consulted

- Hillis LD, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA Guideline for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 124(23): e652–e735.

- Sabik JF, et al. (2011). Coronary bypass surgery. In V Fuster et al., eds., Hurst’s The Heart, 13th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1490–1503. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Current as of: April 9, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:Rakesh K. Pai, MD – Cardiology, Electrophysiology & Martin J. Gabica, MD – Family Medicine & E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & David C. Stuesse, MD – Cardiac and Thoracic Surgery

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.