Top of the pageActionset

Diabetes: Eating Low-Glycemic Foods

Introduction

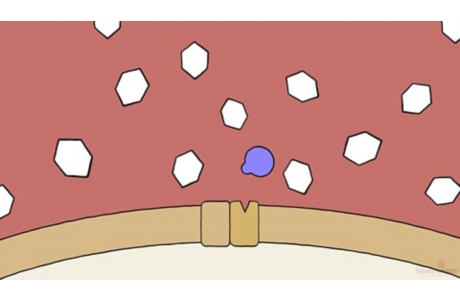

Eating low-glycemic foods is one tool to help keep your diabetes under control. The glycemic index is a rating system for foods that contain carbohydrate. It helps you know how quickly a food with carbohydrate raises blood sugar, so you can focus on eating foods that raise blood sugar slowly.

- Foods that raise blood sugar slowly have a low glycemic index. Most of the carbohydrate-rich foods that you eat with this plan should be low or medium on the glycemic index.

- Eating low-glycemic foods is most helpful when used along with another eating plan for diabetes, such as carbohydrate counting or the plate format. Counting carbs helps you know how much carbohydrate you’re eating. The amount of carbohydrate you eat is more important than the glycemic index of foods in helping you control your blood sugar. The plate format helps you control portions and choose from a variety of foods.

- The glycemic index of a food can change depending on the variety of the food (for example, red potato or white potato), its ripeness, how it is prepared (for example, juiced, mashed, or ground), how it is cooked, and how long it is stored.

- People respond differently to the glycemic content of foods. And because many things affect the glycemic index, the only way to know for sure how a food affects your blood sugar is to check your blood sugar before and after you eat that food.

- High-glycemic foods are rarely eaten by themselves, so the glycemic index might not be helpful unless you’re eating a food by itself. Eating foods together changes their glycemic index.

- Look at the overall nutrition in foods—and not just their glycemic index—when you plan meals. Some low-glycemic foods, such as ice cream, are high in saturated fat and should be eaten only now and then. And some high-glycemic foods, such as potatoes, have nutrients like vitamin C, potassium, and fiber.

- Eating low-glycemic foods along with high-glycemic foods also can help keep your blood sugar from rising quickly.

How do you follow a low-glycemic eating plan?

You don’t have to deny yourself certain food groups or favorite dishes when you follow a low-glycemic eating plan. You focus on eating measured amounts of low- or medium-glycemic foods and trying to eat a balanced diet.

Write down what you eat now

The first step is to look at the kinds of foods you’re eating now. Write down the carbohydrate-rich foods you eat over several days. Then find the glycemic index of these foods.

Foods in the index are given a number from 0 to 100. The higher the number, the higher the glycemic index. Foods are compared to glucose, which is sugar. It has a rank of 100.

- Foods that raise blood sugar quickly are high. They are rated 70 or more.

- Foods that raise blood sugar moderately are medium. They are rated 56 to 69.

- Foods that raise blood sugar slowly are low. They are rated 55 or less.

|

Fruits |

Glycemic index |

|

Apples |

Low |

|

Oranges |

Low |

|

Watermelon |

High |

|

Vegetables |

Glycemic index |

|

Potato, baked (such as russet) |

High |

|

Pumpkin |

High |

|

Sweet potato |

Low |

|

Dried and canned beans and legumes |

Glycemic index |

|

Kidney beans |

Low |

|

Lentils |

Low |

|

Peanuts |

Low |

|

Cereals and grains |

Glycemic index |

|

Rice (brown) |

Medium |

|

Instant oatmeal |

High |

|

Corn flakes |

High |

|

Breads |

Glycemic index |

|

Whole-grain bread |

Low |

|

Hamburger bun (white) |

Medium |

|

White bread |

High |

|

Pasta |

Glycemic index |

|

Spaghetti (whole wheat) |

Low |

|

Spaghetti (white) |

Low |

|

Macaroni |

Low |

Under columns labeled low, medium, or high, list the different foods you eat, according to their glycemic index. You can see at a glance how many high-, medium-, and low-glycemic foods you eat. You may find that you already are eating many foods that are low or medium on the index. But you also may find many foods that are high-glycemic or on the high end of medium.

A dietitian or certified diabetes educator can help you pick foods that you like and that are low on the index. You can get more information from the American Diabetes Association at www.diabetes.org.

Swap some high-glycemic foods with low-glycemic choices

Look at your list for high-glycemic foods that you eat only now and then or that you wouldn’t mind removing from your diet.

Find some low-glycemic choices that you could eat in place of those high-glycemic foods. So, for example, if you like baked potatoes, try having a baked yam instead. If you often eat a plain bagel for breakfast, try a slice of multi-grain toast instead. Watermelon is a fine treat once in a while in the summer. But you could limit how much of it you eat. Or you could have strawberries or other low-glycemic berries instead.

Follow some tips to make low-glycemic choices

- Eat unprocessed food as often as you can. Whole, unprocessed food usually (but not always) has a lower glycemic index than the same food when it’s processed. For example, white bread is more processed than whole wheat bread.

- Don’t overcook pasta. Cooking pasta until well done raises its glycemic index. For a lower glycemic index, pull the pasta out of the water when it’s still a little firm—but not hard—when you bite it.

- Choose high-fiber foods. Most food that is high in fiber takes longer to digest and raises blood sugar slowly.

- Eat measured portions of high-glycemic foods. You can still eat food with a high glycemic index. Many of these foods have nutrients that you need. But try to eat small portions.

- Eat a low-glycemic food along with a high-glycemic food. The low-glycemic food will help counter the effect of the high-glycemic food, so your blood sugar may rise more slowly. Adding a healthy fat to your meal also will slow the rise of your blood sugar. For example, add a small amount of olive oil when you roast potatoes. Although sticky rice has a high glycemic index, eating it with chicken and vegetables will lower its glycemic index.

- Choose whole grains. Use whole-grain bread for your toast in the morning, and eat whole grains at lunch. Whole grains include barley, brown rice, and 100% whole-grain bread.

- When eating out, choose dishes with non-starchy vegetables. Most non-starchy vegetables are low on the glycemic index.

Set goals and get support

- Have your own reasons for wanting to try this eating plan.

- Set a main goal. Then start with smaller goals that will help you reach your larger goal. For example, if your main goal is to eat only one high-glycemic food a day—and you now eat seven high-glycemic foods a day—you could make a smaller goal to remove one or two of those high-glycemic foods from your diet each week.

- Think about what might get in your way. Know that you may have slip-ups, and prepare for how you’ll deal with them. Perhaps you went out to eat and had a meal with several high-glycemic foods. Instead of being upset with yourself, you could try to make a plan for the next time you go out to eat. You might be able to look at the menu online beforehand. That way, you can pick low- or medium-glycemic foods ahead of time.

- Get support as you make a change in your diet. Ask friends or family to encourage you. They might even want to join you in eating more low-glycemic foods.

References

Citations

- Atkinson FS, et al. (2008). International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care, 31(12): 2281–2283.

- American Diabetes Association (2013). The Glycemic Index of Foods. Available online: http://www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/planning-meals/the-glycemic-index-of-foods.html.

Other Works Consulted

- American Diabetes Association (2013). Nutrition therapy recommendations for the management of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care, 36(11): 3821–3842. DOI: 10.2337/dc13-2042. Accessed December 5, 2013.

- American Diabetes Association (2013). The Glycemic Index of Foods. Available online: http://www.diabetes.org/food-and-fitness/food/planning-meals/the-glycemic-index-of-foods.html.

- Atkinson FS, et al. (2008). International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care, 31(12): 2281–2283.

- Franz MJ (2012). Medical nutrition therapy for diabetes mellitus and hypoglycemia of nondiabetic origin. In LK Mahan et al., eds., Krause’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process, 13th ed., pp. 675–710. St Louis: Saunders.

Credits

Current as of: April 16, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Rhonda O’Brien MS, RD, CDE – Certified Diabetes Educator & Colleen O’Connor PhD, RD – Registered Dietitian

Current as of: April 16, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Rhonda O’Brien MS, RD, CDE – Certified Diabetes Educator & Colleen O’Connor PhD, RD – Registered Dietitian

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.