Epilepsy

Topic Overview

What is epilepsy?

Epilepsy is a common condition that causes repeated seizures. The seizures are caused by bursts of electrical activity in the brain that are not normal. Seizures may cause problems with muscle control, movement, speech, vision, or awareness. They usually don’t last very long, but they can be scary. The good news is that treatment usually works to control and reduce seizures.

Epilepsy is not a type of mental illness or intellectual disability. It generally does not affect how well you think or learn. You can’t catch epilepsy from other people (like a cold), and they can’t catch it from you.

What causes epilepsy?

Often doctors do not know what causes epilepsy. Less than half of people with epilepsy know why they have it.

Sometimes another problem, such as a head injury, brain tumor, brain infection, or stroke, causes epilepsy.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptom of epilepsy is repeated seizures that happen without warning. Without treatment, seizures may continue and become worse and more frequent over time.

There are different kinds of seizures. You may have only one type of seizure. Some people have more than one type. Depending on what kind of seizure you have:

- Your senses may not work right. For example, you may notice strange smells or sounds.

- You may lose control of your muscles.

- You may fall down, and your body may twitch or jerk.

- You may stare off into space.

- You may faint (lose consciousness).

Not everyone who has seizures has epilepsy. Sometimes seizures happen because of an injury, illness, or another problem. In these cases, the seizures stop when that problem improves or goes away.

How is epilepsy diagnosed?

Diagnosing epilepsy can be hard. If you think that you or your child has had a seizure, your doctor will first try to figure out if it was a seizure or something else with similar symptoms. For example, a muscle tic or a migraine headache may look or feel like a kind of seizure.

Your doctor will ask lots of questions to find out what happened to you just before, during, and right after a seizure. Your doctor will also examine you and do some tests, such as an EEG. This information can help your doctor decide what kind of seizures you have and if you have epilepsy.

How is it treated?

Medicine controls seizures in many people who have epilepsy. It may take time and careful, controlled changes by you and your doctor to find the right combination, schedule, and dosing of medicine to best manage your epilepsy. The goal is to prevent seizures and cause as few side effects as possible. After you find a medicine that works for you, take it exactly as prescribed. The best way to prevent more seizures is to keep the right amount of the medicine in your body. To do that, you need to take the medicine in the right dose and at the right times every day.

If medicine alone does not control your seizures, your doctor may try one or more of these other treatments. They include:

- Surgery to remove damaged tissue in the brain or the area of brain tissue where seizures begin.

- A special diet called the ketogenic diet. With this diet, you eat a lot more fat and less carbohydrate. This diet reduces seizures in some children who have epilepsy.

- A device called a vagus nerve stimulator. Your doctor implants the device under your skin near your collarbone. It sends weak signals to the vagus nerve in your neck and to your brain to help control seizures.

- A device called a responsive neurostimulation system. Your doctor implants the device inside your skull. It senses when a seizure may be starting and sends a weak signal to prevent the seizure.

How will epilepsy affect your life?

Epilepsy affects each person differently. Some people have only a few seizures. Other people get them more often. Usually seizures are harmless. But depending on where you are and what you are doing when you have a seizure, you could get hurt. Talk to your doctor about whether it is safe for you to drive or swim.

If you know what triggers a seizure, you may be able to avoid having one. Getting regular sleep and avoiding stress may help. If treatment controls your seizures, you have a good chance of living and working like everyone else.

But seizures can happen even when you do everything you are supposed to do. If you continue to have seizures, help is available. Ask your doctor about what services are in your area.

For parents, it is normal to worry about what will happen to your child if he or she has a seizure. But it is also important to help your child live, play, and learn like other children. Talk to your child’s teachers and caregivers. Teach them what to do if your child has a seizure.

There are many ways to lower your child’s risk of injury and still let him or her live as normally as possible. For example, learn about water safety for children who have seizures.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Epilepsy may develop even though you do not have any risk factors (things that increase your risk). A cause cannot always be identified. This is especially true in many forms of childhood epilepsy. For some people, epilepsy can result from a tumor, infection, or damage to the brain.

Children and older adults are most likely to develop epilepsy, but it can start at any age. It is possible that epilepsy may run in families. But you do not have to have a family history to develop epilepsy.

Epileptic seizures occur when abnormal bursts of electricity in the brain briefly upset normal brain function. It’s not always clear what triggers the bursts of abnormal electrical activity.

Conditions that can cause seizures include:

- Head injury.

- Stroke or conditions that affect the blood vessels (vascular system) in the brain.

- Hardening of the arteries (atherosclerosis) in the brain.

- Brain tumor.

- Brain infection, such as meningitis or encephalitis.

- Alzheimer’s disease.

- Substance use disorder or withdrawal.

Tumors, scar tissue from injury or disease, or abnormal brain development may damage a specific area of the brain and cause partial seizures. But you may not have any of these conditions and still develop epilepsy.

Symptoms

Seizures are the only visible symptom of epilepsy. There are different kinds of seizures, and symptoms of each type can affect people differently. Seizures typically last from a few seconds to a few minutes. You may be alert during the seizure or lose consciousness. You may not remember what happened during the seizure or may not even realize you had a seizure.

Seizures that make you fall to the ground or make the muscles stiffen or jerk out of control are easy to recognize. But many seizures do not involve these reactions and may be harder to notice. Some seizures make you stare into space for a few seconds. Others may consist only of a few muscle twitches, a turn of the head, or a strange smell or visual disturbance that only you sense.

Epileptic seizures often happen without warning, although some people may have an aura at the start of a seizure. A seizure ends when the abnormal electrical activity in the brain stops and brain activity begins to return to normal. Seizures may be either partial or generalized.

Partial seizures

Partial seizures begin in a specific area or location of the brain. The most common types of partial seizures are:

- Simple partial seizures.Simple partial seizures do not affect consciousness or awareness.

- Complex partial seizures.Complex partial seizures do affect level of consciousness. You may become unresponsive or may lose consciousness completely.

- Partial seizures with secondary generalization. Partial seizures with secondary generalization begin as simple or complex partial seizures but then spread (generalize) to the rest of the brain and look like generalized tonic-clonic seizures. These two types can easily be confused, but they are treated differently. Most tonic-clonic seizures in adults begin as partial seizures and are caused by partial epilepsy. Generalized tonic-clonic seizures are more common in children.

Generalized seizures

Seizures that begin over the entire surface of the brain are called generalized seizures. The main types of generalized seizures are:

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures(grand mal seizures), during which the person falls to the ground, the entire body stiffens, and the person’s muscles begin to jerk or spasm (convulse).

- Absence seizures (petit mal seizures), which make a person stare into space for a few seconds and then “wake up” without knowing that anything has happened.

- Myoclonic seizures, which make the body jerk like it is being shocked.

- Atonic seizures, in which a sudden loss of muscle tone makes the person fall down without warning.

- Tonic seizures, in which the muscles suddenly contract and stiffen, often causing the person to fall down.

People may refer to seizures as convulsions, fits, or spells. But seizure is the correct term. Convulsions, during which the muscles twitch or jerk, are just one characteristic of seizures. Some seizures cause convulsions, but many do not.

Epileptic seizures are sometimes confused with psychogenic seizures, which are not due to abnormal electrical function. A psychogenic seizure may be a psychological response to stress, injury, emotional trauma, or other factors.

Types of epilepsy

There are many types of epilepsy. All types cause seizures. It can be hard to determine what type of epilepsy you have because of the numerous possible causes, because different types of seizures can occur in the same person, and because the types may affect each person differently.

Some specific types of epilepsy are:

- Benign focal childhood epilepsy, which causes muscles all over the body to stiffen and jerk. These usually occur at night.

- Childhood and juvenile absence epilepsy, which causes staring into space, eye fluttering, and slight muscle jerks.

- Infantile spasms (West syndrome), which causes muscle spasms that affect a child’s head, torso, and limbs. Infantile spasms usually begin before the age of 6 months.

- Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, which causes jerking in the shoulders or arms.

- Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, which causes frequent and several different types of seizures to occur. This syndrome can lead to falls during a seizure, which can cause an injury.

- Temporal lobe epilepsy (the most common type of epilepsy in adults), which causes smacking of the lips or rubbing the hands together, emotional or thought disturbances, and hallucinations of sounds, smells, or tastes.

Epilepsy is not a form of intellectual disability or mental illness. Although a few forms of childhood epilepsy are linked with below-average intelligence and problems with physical and mental development, epilepsy does not cause these problems. Seizures may look scary or strange, but they do not make a person crazy, violent, or dangerous.

Not everyone who has a seizure has epilepsy. Seizures that are not epileptic may result from several different medical conditions such as poisoning, fever, fainting, or alcohol or drug withdrawal. Seizures that occur at the time of a disease, injury, or illness and stop when the condition improves are not related to epilepsy. But if seizures occur repeatedly (become chronic), occurring weeks, months, or even years after the injury or illness, you have developed epilepsy as a result of the condition.

There are several other conditions with similar symptoms, such as fainting or seizures caused by high fevers.

What Happens

Although epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders involving the nervous system, experts often cannot explain exactly how or why the disease develops and how or why the abnormal electrical activity in the brain occurs. Epilepsy does not always follow a predictable course. It can develop at any age and may get worse over time or get better.

Although uncommon, epilepsy that begins in a specific area of the brain may eventually affect another part of the brain. Some types of childhood epilepsy disappear after the child reaches the teenage years. Other types may continue for life. Epilepsy that started after a head injury may disappear after several years or may last the rest of your life.

There is no cure for epilepsy. But treatment can control epileptic seizures, sometimes preventing them from ever occurring again.

Quality of life

Epilepsy and uncontrolled seizures can put limitations on your independence, self-esteem, and quality of life. With epilepsy, you may have trouble getting or keeping a driver’s license. If you become pregnant, complications can occur. Your career choices may be limited. Some people with epilepsy face discrimination at work or school due to other people’s fears and misconceptions about this condition.

The good news is that proper treatment may allow you to control seizures, which can lead to improved quality of life and allow you to better cope with the disorder.

Finding out you have epilepsy can be hard. You may not be able to do some of the things you used to take for granted (such as driving a car). Epilepsy is also a disease that can be hard to treat for some people, especially at first. You may need to try many different types of medicines before you find one that works just right. All of these things may make you feel sad or angry. It may help you to talk to a psychologist or counselor if you are feeling bad about having epilepsy.

Concerns about mental health or intelligence

Epilepsy does not cause and is not a form of mental illness. And in general it does not affect your ability to think and learn. Most people with epilepsy have average intelligence. Children with epilepsy may have a hard time performing in school, but this is usually not the result of below-average intelligence. Frequent absence seizures, for instance, may explain why a child seems to “zone out” or not pay attention during class. Some medicines used to control seizures may affect a child’s ability to stay focused at school.

A few, rare childhood epilepsy syndromes are exceptions to this in that they are typically associated with below-average intelligence, delayed physical and mental development, and other problems. These include infantile spasms (West syndrome), Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Rasmussen syndrome, among others. Tests, such as neuropsychological tests, can help your doctor find out if a problem in the brain is affecting your child’s ability to reason, concentrate, solve problems, or remember.

Because epilepsy is often a lifelong (chronic) disease, it can be hard to understand how much your life will change. Some people may have feelings of despair, depression, or anxiety after hearing that they have epilepsy. In some studies, adults with epilepsy had a higher risk of suicide, especially if they had also been diagnosed with depression or another mental illness, and especially within 6 months of being diagnosed with epilepsy.footnote 1For more information on depression, see the topic Depression.

If you or another adult friend or family member was just diagnosed with epilepsy or just started a new treatment for epilepsy, you may want to watch for suicidal thoughts or threats. For more information on what to watch for, see the topic Suicidal Thoughts or Threats.

Complications of seizures

Epileptic seizures themselves usually cause no harm—the danger lies in where you are or what you are doing when the seizure occurs. There is always a risk of head injury, broken bones, and other injuries from falling or from drowning if you are swimming or bathing at the time of the seizure. It can be dangerous to be operating machinery or driving when you have a seizure. You cannot swallow your tongue during seizures. But you can choke on food, vomit, or an object in your mouth.

Some seizures may place temporary but severe stress on the body and cause problems with the muscles, lungs, or heart. Choking or an abnormal heartbeat may cause sudden death, though this is rare. Untreated seizures that become more severe or frequent may lead to these problems.

More serious complications of epilepsy are uncommon but may include:

- Status epilepticus. This is a prolonged seizure condition that can result in brain damage or death.

- Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). There is a small risk of sudden unexpected death for people with epilepsy. This risk may be higher in people with frequent tonic-clonic seizures or uncontrolled seizures.

What Increases Your Risk

The risk for epilepsy increases if you have:

- Family history of epilepsy.

- Head injury (for example, a penetrating wound or skull fracture) with amnesia or loss of consciousness for more than 24 hours. The more severe the injury, the higher the risk.

- Stroke or conditions that affect the blood vessels (vascular system) in the brain.

- Brain tumor.

- Brain infection, such as encephalitis or meningitis.

- Lead poisoning.

- Problems with brain development that occurred before birth.

- Used illegal drugs, like cocaine.

- Fever seizures that last a long time (also known as febrile convulsions).

- Alzheimer’s disease.

Epilepsy may develop even though you do not have any risk factors. This is especially true of many forms of childhood epilepsy.

When should you call your doctor?

Seizures do not always require urgent care. But call 911 or other emergency services immediately if:

- The person having a seizure stops breathing for longer than 30 seconds. After calling 911 or other emergency services, begin rescue breathing. For more information, see the topic Dealing With Emergencies.

- The seizure lasts longer than 3 minutes. (The person may have entered a life-threatening state of prolonged seizure called status epilepticus.)

- More than one seizure occurs within 24 hours.

- The person having a seizure does not respond normally within 1 hour after the seizure or has any of the following symptoms:

- Reduced awareness and wakefulness or is not fully awake

- Confusion

- Nausea or vomiting

- Dizziness

- Inability to walk or stand

- Fever

- A seizure occurs after the person complains of a sudden, severe headache.

- A seizure occurs with signs of a stroke, such as trouble speaking or understanding speech, loss of vision, and inability to move part or all of one side of the body.

- A seizure follows a head injury.

- A pregnant woman or a woman who has recently had a baby has a seizure. This could be a sign of preeclampsia (toxemia of pregnancy).

- A person with diabetes has a seizure. Low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) or very high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) can cause seizures in a person who has diabetes.

- A seizure occurs after eating poison or breathing fumes.

If you have a seizure for the first time or you witness someone having a seizure, call a doctor immediately. For more information, see the topic Seizures.

If you have been diagnosed with epilepsy, call your doctor if:

- Your seizures become more frequent or more severe.

- A serious illness seems to be changing the normal pattern, frequency, length, or other features of your seizures.

- The normal pattern or features of your seizures change. For example, you have never lost consciousness during a seizure before, but now you do. Or you have never fallen down during a seizure, but now this is happening.

- You are taking antiepileptic medicine and the side effects seem more severe than expected. When you begin taking a medicine, talk to your doctor about what side effects you can expect and what problems might mean that your medicine levels are too high (drug toxicity). You may start having seizures more often if your medicine levels are too low.

- You are pregnant or thinking about becoming pregnant.

Watchful waiting

Watchful waiting is appropriate if you have already been diagnosed with epilepsy and you have a seizure. But call your doctor right away if you have a second seizure within a short period of time or if your seizures have become more frequent or more severe. Your doctor may need to change the amount of medicine you take or try a different medicine.

If you know someone who has epilepsy, learn what to do when the person has a seizure.

Who to see

If you or your child has a seizure for the first time, contact your or your child’s doctor to discuss the event and its potential cause. Your doctor may refer you to a neurologist. Your regular doctor may be able to supervise your epilepsy treatment after your seizures are under control.

People with epilepsy who have trouble controlling seizures and need special care, tests, or surgery can get help at epilepsy centers. The staff at epilepsy centers include doctors and other health professionals trained in treating people with this disorder.

Exams and Tests

Making the correct diagnosis is vital to identifying the appropriate treatment to control seizures.

Diagnosing epilepsy can be quite difficult. When you consult a doctor after you or your child has had unexplained seizures, you and the doctor will work together to answer three questions:

- Was the event a seizure, or was it something that looked like a seizure? Several conditions can appear to be seizures but are not in fact seizures. (These might include breath-holding spells, migraine headaches, muscle twitches or tics, sleep disorders, or psychogenic seizures.) Taking antiepileptic medicines to treat nonepileptic seizures can expose you or your child to unnecessary risks.

- If you are having seizures, are the seizures caused by epilepsy? Not everyone who has a seizure has epilepsy. The seizure may have been caused by something else (such as fever, certain medicines, an electrolyte imbalance, or inhaling fumes). Taking antiepileptic medicines when you do not have epilepsy may put you at unnecessary risk from possible side effects.

- If you have or may have epilepsy, what types of seizures are you having? The different types of epileptic seizures (partial and generalized) are not treated in the same way or with the same medicines. For example, some medicines that control complex partial seizures may make absence seizures worse.

A physical exam and detailed medical history often provide the best clues as to whether you have epilepsy and what type of epilepsy and seizures you have. Discussing what happens to you just before, during, and right after a seizure can help the doctor make a diagnosis.

Your doctor may want to rule out other possible causes for the seizures with other laboratory tests, which may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC) to check for infection, and blood chemistry tests to check for abnormal electrolyte levels (such as magnesium, sodium, and calcium), signs of kidney or liver malfunction, and other common problems.

- Lumbar puncture (sometimes called a spinal tap), which is an analysis of spinal fluid evaluated to rule out infections, such as meningitis and encephalitis.

- Toxicology screen, which examines blood, urine, or hair to look for poisons, illegal drugs, or other toxins.

Electroencephalogram (EEG)

The most useful test in support of a diagnosis of epilepsy is an electroencephalogram (EEG). A computer records your brain’s electrical patterns as wavy lines. If you have epilepsy, the EEG may show abnormal spikes or waves in your brain’s electrical activity patterns. Different types of epilepsy cause different patterns. But an EEG is limited in its ability to diagnose epilepsy. And many people with epilepsy have normal EEGs in between seizures.

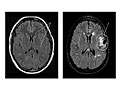

Imaging tests (MRI and CT)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) are imaging tests that allow a doctor to view the brain and evaluate the cause and location of a possible source of epilepsy within the brain. The scans can reveal scar tissue, tumors, or structural problems in the brain that may be the cause of seizures or epilepsy. MRI is the more helpful test in most cases. Imaging tests may not be done after a first seizure, but they are recommended in many situations (such as after a first seizure in adults or after a head injury).

Treatment Overview

Treatment can reduce or prevent seizures in most people who have epilepsy. This can improve quality of life. Controlling your epilepsy also lowers the risk of falling and other complications that can happen when you have a seizure.

First your doctor will figure out what type of epilepsy and what kinds of seizures you have. Treatment that controls one kind of seizure may have no effect on other kinds. Your doctor will also think about your age, health, and lifestyle when he or she plans your treatment.

It may take time for you and your doctor to find the right combination, schedule, and dosage of medicines to manage your epilepsy. The goal is to prevent seizures while causing as few side effects as possible. With the help of your doctor, you can weigh the benefits of a particular treatment against its drawbacks, including side effects, health risks, and cost.

After you and your doctor figure out the treatment that works best for you, make sure to follow your treatment exactly as prescribed.

Initial treatment

Initial treatment for epilepsy depends on the severity, frequency, and type of seizures and whether a cause for your condition has been identified. Medicine is the first and most common approach. Antiepileptic medicines do not cure epilepsy. But they help prevent seizures in well over half of the people who take them.

It is not always clear whether to begin treatment after a first seizure. It is hard to predict whether you will have more seizures. Antiepileptic medicines are not usually prescribed unless you have risk factors for having another seizure, such as brain injury, abnormal test results, or a seizure that occurred at night.

Ongoing treatment

If epileptic seizures continue even though you are being treated, additional or other antiepileptic medicines may be tried.

In addition to medicines, other treatments, such as special diets and surgery, may be added to help reduce the frequency and severity of epileptic seizures.

Surgery is not used just as a last resort to treat epilepsy. Although brain surgery may sound frightening, it can successfully reduce seizures that are harmful, severe, frequent, or do not respond to medicines. Surgery can greatly improve the lives of some carefully screened people who have epilepsy. If you would like to know if surgery is a good choice for you, talk with your doctor.

What to think about

Early treatment may reduce the risk of progressing to more frequent and severe seizures.

You are more likely to have additional seizures if you have had two or more seizures. Doctors usually recommend treatment in these cases.

Prevention

Since the cause of epilepsy is often not clear, it generally is not possible to prevent it.

Head injury, a common cause of epilepsy, may be preventable. Always wear your seat belt in the car and a helmet when riding a bike or motorcycle, skiing, skating, or horseback riding.

Home Treatment

Controlling seizures caused by epilepsy requires a daily commitment to following your treatment plan. If you are using antiepileptic medicine, you must take your medicine exactly as prescribed. Not following the treatment plan is one of the main reasons why medicines fail to control seizures.

Antiepileptic medicines will work only if you keep the right medicine level in your body. Your doctor will set up a schedule of medicine dosages that keeps the proper medicine levels in your body. Missing one or more doses can throw the whole system off.

The same rule about following your treatment plan applies if you or your child is on a special ketogenic diet. The ketogenic diet can be hard to follow, but it must be followed exactly.

As you follow your treatment plan, also try to identify and avoid things that may make you more likely to have a seizure, such as:

- Not getting enough sleep.

- Using drugs or alcohol.

- Being emotionally stressed.

- Skipping meals.

If you continue to have seizures despite treatment, keep a record( What is a PDF document? ) of any seizures you have. Note the date, time of day, and any details about the seizure that you can remember. Your doctor can use information about your seizures to plan or adjust your medicine or other treatment. If you have not been diagnosed with epilepsy, a record of your seizures can help your doctor figure out whether you might have epilepsy and what kinds of seizures you are having.

If your child or someone else in your family has epilepsy, learn what to do when someone has a seizure.

If you have epilepsy (or your child has epilepsy):

- Be sure that any doctor treating you for any condition knows that you have epilepsy and knows what medicines you are taking, if any.

- Wear a medical identification bracelet. In the event of a seizure or accident that leaves you unconscious or unable to speak for yourself, a medical ID bracelet will let those who are treating you know that you have epilepsy. It will also list any medicines you are taking to control your seizures so that you are not given any medicines that will react badly with those already in your body.

If you have a child with epilepsy, there are other tips for parents that may be helpful.

Medications

Medicines to prevent epileptic seizures are called antiepileptics. The goal is to find an effective antiepileptic medicine that causes the fewest side effects.

Although many people experience side effects, medicine is still the best way to prevent epileptic seizures. The benefits of treatment with medicine usually outweigh the drawbacks.

There are many antiepileptic medicines (called AEDs, anticonvulsants, or antiseizure medicines). But they do not all treat the same types of seizures. The first step your doctor takes in choosing a medicine to treat your seizures is to identify the types of seizures you have.

It may take time and careful, controlled adjustments by you and your doctor to find the combination, schedule, and dosing of medicine to best manage your epilepsy. The goal is to prevent seizures while causing as few side effects as possible. After you and your doctor figure out the medicine program that works best for you, make sure to follow your program exactly as prescribed.

Using a single antiepileptic medicine is often better than using more than one medicine. Single medicine use causes fewer side effects and does not carry the risk of interacting with other medicines. The chances of missing a dose or taking it at the wrong time are also lower with just one medicine.

When treatment with one medicine doesn’t help you enough, your doctor may suggest a second medicine to help improve seizure control. Also, if you have several types of seizures, you may need to take more than one medicine.

Medicine choices

Many medicines are used to treat epilepsy. Some are used alone, and some are used only along with other medicines. Your medicine options depend in part on what types of seizures you have. The medicines listed below are not the only medicines used for epilepsy, but they are the most common.

Medicines used for partial seizures, including those with secondary generalization

- Carbamazepine (such as Carbatrol).

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Oxcarbazepine (such as Trileptal).

Medicines used for primary generalized (tonic-clonic) seizures

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Valproate (such as Depakene).

Medicines used for absence seizures

- Ethosuximide (Zarontin)

- Valproate (such as Depakene).

Medicines used for atypical absence, myoclonic, or atonic seizures

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal)

- Levetiracetam (Keppra)

- Valproate (such as Depakene).

Other medicines used for seizures include:

- Clobazam (Onfi).

- Clonazepam (Klonopin).

- Ezogabine (Potiga).

- Felbamate (Felbatol).

- Gabapentin (such as Neurontin).

- Lacosamide (Vimpat).

- Topiramate (such as Topamax).

- Phenobarbital (Luminal).

- Phenytoin (such as Dilantin).

- Pregabalin (Lyrica).

- Rufinamide (Banzel).

- Tiagabine (Gabitril).

- Vigabatrin (Sabril).

- Zonisamide (Zonegran).

See information on:

Many of the medicines listed above control the same types of seizures equally well. Most antiepileptic medicines can cause nausea, dizziness, and sleepiness when you first start taking them. But these effects usually go away after your body adjusts to the medicine. Liver and blood problems are common to many of them. You may need to have regular blood tests to watch for these side effects as long as you are taking the medicines.

Aside from these common problems, though, the medicines have different side effects, health risks, and costs. A medicine that works for someone else may not work for you.

When the more commonly used medicines fail to control seizures or cannot be used for some other reason, you may still have other medicine options.

- Many new medicines are being developed and tested in clinical trials but are not in regular use yet. One of these might be an option. People with epilepsy who have not responded to standard therapy sometimes choose to take part in these trials. To learn more about clinical trials, talk to your doctor or visit the National Institutes of Health clinical trials website at www.clinicaltrials.gov.

- There are also a few medicines that are only used for certain rare or severe forms of epilepsy in children. Children with infantile spasms, for instance, may respond to a corticosteroid, vigabatrin, or adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

What to think about

All antiepileptic medicines have some unpleasant side effects. Ideally, medicine works to prevent seizures without causing intolerable side effects.

When choosing between medicines that treat the same type of seizure, you and your doctor will think about things such as:

- How well the medicine works. How well a medicine works usually influences your willingness to take it.

- Possible side effects of each medicine.

- Long-term health risks of each medicine.

- How often each medicine has to be taken.

- Your age. Side effects may not affect children and adults in the same way. Medicines that can affect memory and thought processes may have a more severe impact on older adults.

- Your medical history and other health concerns that might affect the use of a medicine. For instance, many antiepileptic medicines can cause rare liver and blood problems and may be very risky if you already have liver disease or a blood disorder.

- The doctor’s own experience in treating people with each medicine.

- The cost of each medicine.

Building a medicine routine that works can be hard. Finding the correct dosage of a medicine may take months. Some people may have skin rashes, nausea, loss of coordination, and other short-term problems when they first start taking medicine for epilepsy. When the first medicine you try does not prevent seizures or you cannot tolerate its side effects, the doctor may have to start the process all over again with a different medicine. The chances of medicine therapy failure increase as the number of medicines tried increases.

If you or your child has epilepsy and needs to begin or change a medicine routine, talk to your doctor about what to expect from treatment with the medicine. You may or may not have a choice between medicines, depending on the types of seizures you or your child has and other factors. Thinking about and asking questions about antiepileptic medicines will help you prepare for the treatment.

Pregnancy raises special concerns for women who take antiepileptic medicines. Before you become pregnant, be sure to talk to your doctor about how to handle your treatment.

You may think about stopping medicines if you have not had a seizure in several years. About 6 to 7 out of 10 people in this situation are able to stop taking antiepileptic medicines without having another seizure again for several years.footnote 2 But do not stop taking your medicine without first talking with your doctor.

FDA Advisory. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an advisory on antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and the risk of suicide. Talk to your doctor about these possible side effects and the warning signs of suicide in adults and in children and teens.

Surgery

Even though medicine is the most common approach to treating epilepsy, it does not always work. In almost one-third of people with epilepsy, medicine cannot control their seizures adequately (or at all, in some cases). This number is even higher in people with focal epilepsy. Surgery can greatly improve the lives of some people who have epilepsy.

You may be a good candidate for surgery if your seizures:

- Occur often enough to severely disrupt your life.

- Tend to result in injury or harm (for instance, if seizures cause frequent falls).

- Change or alter your consciousness.

- Are not controlled well with medicine, or you cannot tolerate the side effects of the medicines.

Having frequent or severe seizures often restricts you from driving, doing certain kinds of work, and other activities. Medicine may fail to control these seizures. Or medicine may cause side effects severe enough to disrupt your lifestyle.

Surgery is not an “if all else fails” approach to treating epilepsy. It often may be a better choice than trying each and every medicine. For adults with temporal lobe epilepsy, for instance, surgery may be considered if two different first-line medicines are tried and neither controls the seizures adequately. For certain types of childhood epilepsy—disorders that children cannot outgrow and that do not respond to medicine—having surgery at the youngest possible age may offer the greatest benefit for the child. The younger brain is more adaptable and recovers better after surgery.

Epilepsy surgery removes an area of abnormal tissue in the brain, such as a tumor or scar tissue, or the specific area of brain tissue where seizures begin. Before surgery, you may have several tests (including an electroencephalogram [EEG], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and video monitoring) to find exactly where seizures begin in the brain. After the area of abnormal tissue where your seizures begin has been located, doctors can decide whether or not it can be removed safely.

Surgery is usually done in a hospital that is associated with an epilepsy center. The surgery usually takes a few hours, and you have to stay in the hospital for a few days afterward. It may be several months or more before you feel fully back to normal.

Surgery choices

The type of epilepsy surgery depends on the location in the brain in which seizures start.

The most common surgery is anterior temporal lobectomy, which is the removal of part of one of the brain’s temporal lobes. For many people with temporal lobe epilepsy, this surgery offers a very good chance of becoming seizure-free.

Some types of surgery are usually only done on children.

- Corpus callosotomy helps some children who have Lennox-Gastaut syndrome by reducing falls that happen during seizures. These can happen often and often cause injury to the child.

- Hemispherectomy during the first few years of life may benefit children with other uncommon, severe forms of epilepsy (such as Rasmussen syndrome or Sturge-Weber disease).

What to think about

Surgery can be very effective for some people with epilepsy. But surgery is not an option for everyone. If you or your child has a type of epilepsy that might improve with surgical treatment, you may want to think about some of these issues:

- Surgery is not a last resort. It may be considered after unsuccessfully trying two medicines.

- Early surgery for some forms of childhood epilepsy may end seizures and prevent or reverse developmental delays. Children make good surgical candidates. They tend to recover quickly with fewer problems afterward.

- People who have temporal lobe epilepsy and whose seizures do not get better with medicines may be good candidates for surgery.

- Surgery is not always a cure for epilepsy. Some people never have seizures again after surgery. But for many others, surgery only reduces seizure frequency or severity.

- You need to be healthy to have the surgery and to benefit from it. People with severe illnesses, psychiatric disorders, or neurological problems other than epilepsy may need evaluations from more specialists to see if they are good candidates for epilepsy surgery.

- Epilepsy surgery involves removing part of your brain. It can affect your brain function, although the effects may be less bothersome than those caused by the epilepsy itself. Problems after surgery can be mild to severe—such as less energy, visual defects, language and memory problems, and weakness or partial paralysis on one side of the body—and may be temporary or permanent.

- Brain surgery is an expensive way to treat epilepsy and carries with it many risks. Even if medicine does not prevent your seizures, surgery may not be recommended if you only have seizures once in a while or do not have severe seizures.

Other Treatment

For many years, antiepileptic medicine was the only treatment for people with epilepsy. This is still true for many people, although surgery is now an option for some. Seizures that cannot be controlled with medicine or treated by surgery may sometimes respond to other treatments.

Other treatment choices

Treatments for epilepsy that can be used along with medicines and surgery may include:

- Special diets. For example, the ketogenic diet is a diet that tries to force the body to use more fat for energy (instead of sugar) by severely limiting carbohydrates—such as bread, pasta, fruits, and vegetables—and total calories.

- Nerve stimulation. One device, a vagus nerve stimulator, sends weak electrical signals to the vagus nerve in your neck, which in turn sends the signals to your brain at regular intervals to reduce seizures. Another device, a responsive neurostimulation system, is implanted in your skull. It senses when a seizure may be starting and sends a weak signal to prevent the seizure.

References

Citations

- Christensen J, et al. (2007). Epilepsy and the risk of suicide: A population-based case-control study. Lancet Neurology. Published online July 3, 2007 (doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70175-8).

- Bazil CW, Pedley TA (2010). Epilepsy. In LP Rowland, TA Pedley, eds., Merritt’s Neurology, 12th ed., pp. 927–948. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

Other Works Consulted

- Bell GS, et al. (2008). Drowning in people with epilepsy: How great is the risk? Neurology, 71(8): 578–582.

- Go CY, et al. (2012). Evidence-based guideline update: Medical treatment of infantile spasms. Neurology, 78(24): 1974–1980.

- Jentink J, et al. (2010). Valproic acid monotherapy in pregnancy and major congenital malformations. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(23): 2185–2193.

- Krumholz A, et al. (2007). Practice parameter: Evaluating an apparent unprovoked first seizure in adults (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology, 69(21): 1996–2007.

- Krumholz A, et al. (2015). Evidence-based guideline: Management of an unprovoked first seizure in adults: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Epilepsy Society. Neurology, 84: 1705–1713. DOI: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001487. Accessed May 12, 2015.

- Liow K, et al. (2007). Position statement on the coverage of anticonvulsant drugs for the treatment of epilepsy. Neurology, 68(16): 1249–1250.

- Ropper AH, et al. (2014). Epilepsy and other seizure disorders. In Adams and Victor’s Principles of Neurology, 9th ed., pp. 318–356. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Shneker BF, et al. (2009). Suicidality, depression screening, and antiepileptic drugs: Reaction to the FDA alert. Neurology, 72(11): 987–991.

Current as of: March 28, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:John Pope MD – Pediatrics & E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Martin J. Gabica MD – Family Medicine & Kathleen Romito MD – Family Medicine & Steven C. Schachter MD – Neurology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.