Healthy Eating for Children

Topic Overview

What is healthy eating?

Healthy eating means eating a variety of foods so that your child gets the nutrients (such as protein, carbohydrate, fat, vitamins, and minerals) he or she needs for normal growth. If your child regularly eats a wide variety of basic foods, he or she will be well-nourished.

How much food is good for your child?

With babies and toddlers, you can usually leave it to them to eat the right amount of food at each meal, as long as you make only healthy foods available.

Babies cry to let us know they’re hungry. When they’re full, they stop eating. Things get more complicated at age 2 or 3, when children begin to prefer the tastes of certain foods, dislike the tastes of other foods, and have a lot of variation in how hungry they are. But even then it usually works best to make only healthy foods available and let your child decide how much to eat.

It may worry you to see your child eat very little at a meal. Children tend to eat the same number of calories every day or two if they are allowed to decide how much to eat. But the pattern of calorie intake may vary from day to day. One day a child may eat a big breakfast, a big lunch, and hardly any dinner. The next day this same child may eat very little at breakfast but may eat a lot at lunch and dinner. Don’t expect your child to eat the same amount of food at every meal and snack each day.

How can you help your child eat well and be healthy?

Many parents worry that their child is either eating too much or too little. Perhaps your child only wants to eat one type of food—peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, for instance. One way to help your child eat well and help you worry less is to know what your job is and what your child’s job is when it comes to eating. If your child only wants to eat one type of food, he or she is doing the parent’s job of deciding what food choices are. It is the parent’s job to decide what foods are offered.

- Your job is to offer nutritious food choices at meals and snack times. You decide thewhat, where, and when of eating.

- Your child’s job is to choose how much he or she will eat of the foods you serve. Your child decides how muchor even whether to eat.

If this idea is new to you, it may take a little time for both you and your child to adjust. In time, your child will learn that he or she will be allowed to eat as little or as much as he or she wants at each meal and snack. This will encourage your child to continue to trust his or her internal hunger gauge.

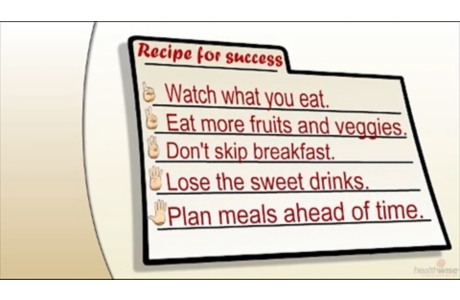

Here are some ways you can help support your child’s healthy eating habits:

- Eat together as a family as often as possible. Keep family meals pleasant and positive. Avoid making comments about the amount or type of food your child eats. Pressure to eat actually reduces children’s acceptance of new or different foods.

- Make healthy food choices for your family’s meals. Children notice the choices you make and follow your example.

- Make meal times fairly predictable. Eat at around the same times every day and always at the table, even for snacks.

- Have meals often enough (for example, about every 3 hours for toddlers) that your child doesn’t get too hungry.

- Do nothing else during the meal other than talking and enjoying each other—no TV or other distractions.

Here are some other ways you can help your child stay healthy:

- Set limits on your child’s daily television and computer time.

- Make physical activity a part of your family’s daily life. For example, walk your child to and from school and take a walk after dinner. Teach your young child how to skip, hop, dance, play catch, ride a bike, and more. Encourage your older child to find his or her favorite ways to be active.

- Take your child to all recommended well-child checkups. You can use this time to discuss with a doctor your child’s growth rate, activity level, and eating habits.

What causes poor eating habits?

Poor eating habits can develop in otherwise healthy children for several reasons. Infants are born liking sweet tastes. But if babies are going to learn to eat a wide variety of basic foods, they need to learn to like other tastes, because many nutritious foods don’t taste sweet.

- Available food choices. If candy and soft drinks are always available, most children will choose these foods rather than a more nutritious snack. But forbidding these choices can make your child want them even more. You can include some less nutritious foods as part of your child’s meals so that he or she learns to enjoy them along with other foods. Try to keep a variety of nutritious and appealing food choices available. Healthy and kid-friendly snack ideas include:

- String cheese.

- Whole wheat crackers and peanut butter.

- Air-popped or low-fat microwave popcorn.

- Frozen juice bars made with 100% real fruit.

- Fruit and dried fruit.

- Baby carrots with hummus or bean dip.

- Low-fat yogurt with fresh fruit.

- The need for personal choice. Power struggles between a parent and child can affect eating behavior. If children are pressured to eat a certain food, they are more likely to refuse to eat that food, even if it is something they usually would enjoy. Provide a variety of nutritious foods. Your child can decide what and how much he or she will eat from the choices you offer.

- Emotion. A child’s sadness, anxiety, or family crisis can cause undereating or overeating. If you think your child’s emotions are affecting his or her eating, focus on resolving the problem that is causing the emotions instead of focusing on the eating behavior.

If your child is healthy and eating a nutritious and varied diet, yet seems to eat very little, he or she may simply need less food energy (calories) than other children. And some children need more daily calories than others the same age or size, and they eat more than you might expect. Every child has different calorie needs.

In rare cases, a child may eat more or less than usual because of a medical condition that affects his or her appetite. If your child has a medical condition that affects how he or she eats, talk with your child’s doctor about how you can help your child get the right amount of nutrition.

What are the risks of eating poorly?

A child with poor eating habits is going to be poorly nourished. That means he or she won’t be getting the amounts of nutrients needed for healthy growth and development. This can lead to being underweight or overweight. Poorly nourished children tend to have weaker immune systems, which increases their chances of illness. Poor eating habits can increase a child’s risk for heart disease, high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, or high cholesterol later in life.

Poor eating habits include:

- Eating a very limited variety of foods.

- Refusing to eat entire groups of foods, such as vegetables.

- Eating too many foods of poor nutritional quality, such as soft drinks, chips, and doughnuts.

- Overeating from being served large portions or being told to “clean your plate” or “finish it all up.”

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Changing Your Family’s Eating Habits

Healthy eating means eating a variety of foods from all food groups. It means choosing fewer foods that have lots of fats and sugar. But it does not mean that your child cannot eat desserts or other treats now and then.

With a little planning, you can create a structure that gives your child (and you) the freedom to make healthy eating choices. Think of this as planning not just for the kids but for everyone in your family.

Getting started with your young child

- At meals, serve milk. (Children under 12 months of age should not drink cow’s milk.) Most children need whole milk between 1 and 2 years of age. But your doctor may recommend 2% milk if your child is overweight or if there is a family history of obesity, high blood pressure, or heart disease. Over the age of 2, serve fat-free or low-fat milk.

- When trying new foods at a meal, be sure to also include a food that your child likes. Don’t be discouraged if it takes several tries before your child actually eats a new food. It may take as many as 15 times or more before your child will try a new food.

- Juice does not have the valuable fiber that whole fruit has. Unless the label says the drink has only 100% juice, beware that many fruit drinks are just water, a little juice flavoring, and a lot of added sugar. If you must give juice, water it down. The American Academy of Pediatrics advises no more than 4 fl oz (120 mL) to 6 fl oz (180 mL) of 100% fruit juice a day for children 1 to 6 years old.footnote 1 This means ½ cup to ¾ cup. Juice isn’t recommended for babies 0 to 12 months.

Planning meals and snacks

- Set up a regular snack and meal schedule. Kids need to eat at least every 3 to 4 hours. Most children do well with three meals and two or three snacks a day.

- Eat meals together as a family as often as possible.

- Start with small, easy-to-achieve changes, such as offering more fruits and vegetables at meals and snacks.

- Look at your portion sizes. Remember that younger children may eat smaller amounts than adults. Although paying attention to portion sizes is important (especially of less nutritious foods), it is up to your child to decide how much food he or she needs to eat at a meal to feel full.

- Cut down on soda pop and other high-sugar drinks. Serve water to quench thirst. You can encourage your child to drink more water and fewer sugar-sweetened drinks by keeping cold water on hand in the refrigerator.

- Consider meeting with a registered dietitian for help with meal and snack planning (nutritional counseling).

- Even though your child may not eat the food, it is important to keep serving it so that your child can see other family members enjoying it. Also, your child should not think that meals are going to be planned only around his or her food preferences. Remember, you are in charge of deciding which foods are served at meal and snacks.

If you are feeling out of control over your own eating habits or weight, your child may be learning some poor eating habits from you. See a registered dietitian, your doctor, or a mental health professional experienced with eating problems, if needed. For more information, see the topics Healthy Eating and Weight Management.

Encouraging healthy choices

Help your child learn to make healthy food and lifestyle choices by following these steps:

- Be a good role model. Practice the eating and exercise habits you’d like your children to have. Your example is your child’s most powerful learning tool.

- Increase active time. Make physical activity a part of your family’s daily life. Set limits on your child’s daily TV and computer time. Have your child take breaks from computer, cell phone, and TV use and be active instead.

- Eat breakfast. Having breakfast with your child can help start a lifelong healthy habit.

- Involve your child in meal planning and grocery shopping. When your child is old enough, teach him or her about food preparation, cooking and food safety and, later, how to use food label information. While giving your child a role in decision making, remember that you have the final say in food planning.

- Involve your child in cooking. Children enjoy helping out, and they learn easily with hands-on experience. They can also use other skills, such as math, when counting or measuring ingredients.

Helping Your Child to Eat Well

Setting the stage for pleasant mealtimes

Make a point to eat as many meals together at home as possible. A regular mealtime gives you and your family a chance to talk and relax together. It also helps you and your child to have a positive relationship with food.

- Think of the family meal table as a conflict-free zone where you each come for positive time together. Save problem solving and difficult discussions for a separate time and place.

- Save distractions, such as reading, toys, television watching, or answering the phone, for another time and place.

- Teach and model good table manners and respectful behavior.

No more power struggles—learning to trust your child’s choices during meals and snacks

Most children self-correct their undereating, overeating, and weight problems when the power struggle is taken out of their mealtimes. But the hardest part for most parents is stopping themselves from directing their children’s choices (“Eat at least one bite of vegetable.” “That’s a lot of bread you’re eating.” “Clean your plate.” “No seconds.”). Do your best to avoid commenting.

If your child skips over certain foods, eats lightly, or eats more than you’d like:

- Check yourself. Remember that your child has an internal hunger gauge that controls how much to eat. If you override those signals, your child won’t be able to tune into that internal hunger gauge as easily.

- Let your child decide when he or she is full. You can remind children of the next scheduled meal or snack time by telling them, for example, “You can eat as much or as little as you want now. We will have our next snack at 4 o’clock.”

Expect some rebellion as you change the way you feed your family. At first, your child may eat only one type of food, eat everything in sight, or stubbornly refuse to eat anything. Fortunately, no harm is done if your child chooses to eat too much or skips a meal once in a while.

Gradually, your child’s eating habits will balance out. You’ll notice that, as long as you provide nutritious choices, your child will eat a healthy variety and amount of food each week. Try to relax, and you’ll see your child relax too.

Adjusting your approach based on your child’s age

Feeding your infant. From birth, infants follow their internal hunger and fullness cues. They eat when they’re hungry, and they stop eating when they’re full. Experts recommend that newborns be fed on demand.

Feeding your toddler/preschooler. As you introduce your young child to new foods, you are encouraging a love of variety, texture, and taste. This is important, because the more adventurous your child feels about foods, the more balanced and nutritious his or her weekly intake will be. Remember that you may need to present a new or different food a number of times before your child will be comfortable trying it. This is normal. The best approach is to offer the new food in a relaxed manner without pressuring your child.

Feeding your teen. When your child becomes a teen, he or she has a lot more food choices outside the home. You are still responsible for providing balanced meals in the home. Family mealtimes become especially important.

Children have special vitamin and mineral needs. For example:

- Infants need a source of iron. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends iron supplementation in breastfed babies starting at 4 months of age for full-term babies and by 1 month of age for preterm babies. Use iron-fortified formula (for formula-fed babies). And when you start your infant on solid foods, include high-iron infant cereals and/or meat baby foods. Infants may need a daily vitamin D supplement. Talk with your doctor about how much and what sources of vitamin D are right for your child.

- Children ages 6 months to 16 years may need a fluoride supplement. Normal amounts of fluoride added to public water supplies and bottled water are safe for children and adults. If your child needs extra fluoride, your dentist may recommend supplements. Use these supplements only as directed. And keep them out of reach of your child. Too much fluoride can be toxic and can stain a child’s teeth.

- Girls ages 9 to 18 years need more calcium and may not get enough calcium from the foods they eat.

Getting help for your child’s eating habits

If you are worried about your child’s eating habits, you can call your family doctor for help. He or she can advise you on actions you can take or direct you to someone with specific expertise, such as:

- Registered dietitians, who teach people about nutrition or develop diets to promote health. They can also specialize in counseling to help treat food-related problems, including eating disorders.

- Primary care pediatricians, who may have special training and experience in caring for children who have eating issues.

- Therapists or counselors, who can help your family cope with eating disorders and with power struggles about eating.

- Psychiatrists, who can provide counseling and medicine.

- Pediatric gastroenterologists, who can rule out or treat conditions of the digestive system, which could cause an eating problem.

- Pediatric endocrinologists, who can rule out or treat hormone conditions that can lead to weight problems.

Call your doctorif:

References

Citations

- Committee on Nutrition, American Academy of Pediatrics (2001, reaffirmed 2006). The use and misuse of fruit juice in pediatrics. Pediatrics, 107(5): 1210–1213. Also available online: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/107/5/1210.full.

Other Works Consulted

- American Academy of Pediatrics (2010). Diagnosis and prevention of iron deficiency and iron-deficiency anemia in infants and young children (0–3 years of age). Pediatrics, 126(5): 1040–1050. Available online: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/126/5/1040.

- Expert Panel on Integrated Guidelines for Cardiovascular Health and Risk Reduction in Children and Adolescents (2011). Expert panel on integrated guidelines for cardiovascular health and risk reduction in children and adolescents: Summary report. Pediatrics, 128(Suppl 5): S213–S256.

- Haemer M, et al. (2014). Normal childhood nutrition and its disorders. In WW Hay Jr et al., eds., Current Diagnosis and Treatment: Pediatrics, 22nd ed., pp. 305–333. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Lucas BL, et al. (2012). Nutrition in childhood. In LK Mahan et al., eds., Krause’s Food and the Nutrition Care Process, 13 ed., pp. 389–409. St Louis: Saunders.

- Nix S (2013). Nutrition during infancy, childhood, and adolescence. In Williams’ Basic Nutrition and Diet Therapy, 14th ed., pp. 195–216. St. Louis: Mosby.

- Whitney E, Rolfes SR (2013). Life cycle nutrition: Infancy, childhood, and adolescence. In Understanding Nutrition, 13th ed., pp. 504–544. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Current as of: November 7, 2018

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:John Pope, MD, MPH – Pediatrics & Kathleen Romito, MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Rhonda O’Brien, MS, RD, CDE – Certified Diabetes Educator

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.