Pulmonary Embolism

Topic Overview

What is pulmonary embolism?

Pulmonary embolism is the sudden blockage of a major blood vessel (artery) in the lung, usually by a blood clot. In most cases, the clots are small and are not deadly, but they can damage the lung. But if the clot is large and stops blood flow to the lung, it can be deadly. Quick treatment could save your life or reduce the risk of future problems.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptoms are:

- Sudden shortness of breath.

- Sharp chest pain that is worse when you cough or take a deep breath.

- A cough that brings up pink, foamy mucus.

Pulmonary embolism can also cause more general symptoms. For example, you may feel anxious or on edge, sweat a lot, feel lightheaded or faint, or have a fast heart rate or palpitations.

If you have symptoms like these, you need to see a doctor right away, especially if they are sudden and severe.

What causes pulmonary embolism?

In most cases, pulmonary embolism is caused by a blood clot in the leg that breaks loose and travels to the lungs. A blood clot in a vein close to the skin is not likely to cause problems. But having blood clots in deep veins (deep vein thrombosis) can lead to pulmonary embolism. More than 300,000 people each year have deep vein thrombosis or a pulmonary embolism.footnote 1

Other things can block an artery, such as tumors, air bubbles, amniotic fluid, or fat that is released into the blood vessels when a bone is broken. But these are rare.

What increases your risk of pulmonary embolism?

Anything that makes you more likely to form blood clots increases your risk of pulmonary embolism. Some people are born with blood that clots too quickly. Other things that can increase your risk include:

- Being inactive for long periods. This can happen when you have to stay in bed after surgery or a serious illness, or when you sit for a long time on a flight or car trip.

- Recent surgery that involved the legs, hips, belly, or brain.

- Some diseases, such as cancer, heart failure, stroke, or a severe infection.

- Pregnancy and childbirth (especially if you had a cesarean section).

- Taking birth control pills or hormone therapy.

- Smoking.

You are also at higher risk for blood clots if you are an older adult (especially older than 70) or extremely overweight (obese).

How is pulmonary embolism diagnosed?

It may be hard to diagnose pulmonary embolism, because the symptoms are like those of many other problems, such as a heart attack, a panic attack, or pneumonia. A doctor will start by doing a physical exam and asking questions about your past health and your symptoms. This helps the doctor decide if you are at high risk for pulmonary embolism.

Based on your risk, you might have tests to look for blood clots or rule out other causes of your symptoms. Tests may include blood tests, a CT angiogram, and a ventilation-perfusion lung scan.

How is it treated?

Doctors usually treat pulmonary embolism with medicines called anticoagulants. They are often called blood thinners, but they don’t really thin the blood. They help prevent new clots and keep existing clots from growing.

Most people take a blood thinner for a few months. People at high risk for blood clots may need it for the rest of their lives.

If symptoms are severe and life-threatening, “clot-busting” drugs called thrombolytics may be used. These medicines can dissolve clots quickly, but they increase the risk of serious bleeding. Another option is surgery or a minimally invasive procedure to remove the clot (embolectomy).

Some people may have a filter put into the large vein (vena cava) that carries blood from the lower body to the heart. A vena cava filter helps keep blood clots from reaching the lungs.

If you have had pulmonary embolism once, you are more likely to have it again. Blood thinners can help reduce your risk, but they increase your risk of bleeding. If your doctor prescribes blood thinners, be sure you understand how to take your medicine safely.

You can reduce your risk of pulmonary embolism by doing things that help prevent blood clots in your legs.

- Avoid sitting for long periods. Get up and walk around every hour or so, or flex your feet often.

- Get moving as soon as you can after surgery.

- Wear compression stockings if you are at high risk.

- If you take blood thinners, take them just the way your doctor tells you to.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

Cause

Pulmonary embolism is caused by a blocked artery in the lungs. The most common cause of such a blockage is a blood clot that forms in a deep vein in the leg and travels to the lungs, where it becomes lodged in a smaller lung artery.

Almost all blood clots that cause pulmonary embolism are formed in the deep leg veins. Clots also can form in the deep veins of the arms or pelvis.

Sometimes blood clots develop in surface veins. But these clots rarely lead to pulmonary embolism.

In rare cases, pulmonary embolism may be caused by other substances, including:

- Small masses of infectious material.

- Fat, which can be released into the bloodstream after some types of bone fractures, surgery, trauma, or severe burns.

- Air bubbles or substances that get into the blood from trauma, surgery, or medical procedures.

- Tumors caused by rapidly growing cancer cells.

Symptoms

The symptoms of pulmonary embolism may include:

- Shortness of breath that may occur suddenly.

- Sudden, sharp chest pain that may become worse with deep breathing or coughing.

- Rapid heart rate.

- Rapid breathing.

- Sweating.

- Anxiety.

- Coughing up blood or pink, foamy mucus.

- Fainting.

- Heart palpitations.

- Signs of shock.

Pulmonary embolism may be hard to diagnose because its symptoms may occur with or are similar to other conditions, such as a heart attack, asthma, a panic attack, or pneumonia. Also, some people with pulmonary embolism don’t have symptoms.

What Happens

If a large blood clot blocks the artery in the lung, blood flow may be completely stopped, causing sudden death. A smaller clot reduces the blood flow and may cause damage to lung tissue. But if the clot dissolves on its own, it may not cause any major problems.

Symptoms of pulmonary embolism usually begin suddenly. Reduced blood flow to one or both lungs can cause shortness of breath and a rapid heart rate. Inflammation of the tissue covering the lungs and chest wall (pleura) can cause sharp chest pain.

Without treatment, pulmonary embolism is likely to come back.

Complications of pulmonary embolism

- Cardiac arrest and sudden death

- Shock

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Death of part of the lung, called pulmonary infarction

- A buildup of fluid (pleural effusion) between the outside lining of the lungs and the inner lining of the chest cavity

- Paradoxical embolism

- Pulmonary hypertension

Doctors will consider aggressive steps when they are treating a large, life-threatening pulmonary embolism.

Chronic or recurring pulmonary embolism

Blood clots that cause pulmonary embolism may dissolve on their own. But if you have had pulmonary embolism, you have an increased risk of a repeat episode if you do not receive treatment. If pulmonary embolism is diagnosed promptly, treatment with anticoagulant medicines may prevent new blood clots from forming.

The risk of having another pulmonary embolism caused by something other than blood clots varies. Substances that are reabsorbed into the body, such as air, fat, or amniotic fluid, usually do not increase the risk of having another episode. Cancer increases the risk of blood clots.

Having multiple episodes of pulmonary embolism can severely reduce blood flow through the lungs and heart. Over time, this increases blood pressure in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension), eventually leading to right-sided heart failure and possibly death.

What Increases Your Risk

Having a blood clot in the deep vein of your leg and having a previous pulmonary embolism are the two greatest risk factors for pulmonary embolism.

For more information on risk factors for blood clots in the legs, see the topic Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Many things increase your risk for a blood clot. These include:

- Having slowed blood flow, abnormal clotting, and a blood vessel injury.

- Age. As people get older (especially older than age 70), they are more likely to develop blood clots.

- Weight. Being overweight increases the risk for developing clots.

- Not taking anticoagulant medicine as prescribed, unless your doctor tells you to stop taking it.

Slowed blood flow

When blood does not circulate normally, clots are more likely to develop. Reduced circulation may result from:

- Long-term bed rest, such as if you are confined to bed after an operation, injury, or serious illness.

- Traveling and sitting for a long time, especially when traveling long distances by airplane.

- Leg paralysis. When you use your muscles, the muscles contract, and that squeezes the blood vessels in and around the muscles. The squeezing helps the blood move back toward the heart. Paralysis can reduce circulation because the muscles can’t contract.

Abnormal clotting

Some people have blood that clots too easily or too quickly. People with this problem are more likely to form larger clots that can break loose and travel to the lungs. Conditions that may cause increased clotting include:

- Inherited factors. Some people have an inherited tendency to develop blood clots that can lead to pulmonary embolism.

- Family history of close relatives, such as a sibling, who has had deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

- Cancer and its treatment.

- Blood vessel diseases, such as varicose veins, heart attack, heart failure, or a stroke.

- Pregnancy. A woman’s risk for developing blood clots increases both during pregnancy and shortly after delivery.

- Using hormone therapy or birth control pills or patches.

- Smoking.

Injury to the blood vessel wall

Blood is more likely to clot in veins and arteries shortly after they are injured. Injury to a vein can be caused by:

- Recent surgery that involved the legs, hips, belly, or brain.

- A tube (catheter) placed in a large vein of the body (central venous catheter).

- Damage from an injury, such as a broken hip, serious burn, or serious infection.

When should you call your doctor?

Call 911 or other emergency services immediately if you think you have symptoms of pulmonary embolism.

Symptoms include:

- Sudden shortness of breath.

- Sharp chest pain that sometimes becomes worse with deep breathing or coughing.

- Coughing up blood.

- Fainting.

- Rapid pulse or irregular heartbeat.

- Anxiety or sweating.

Call your doctor immediately if you have symptoms of a blood clot in the leg, including:

- Swelling, warmth, or tenderness in the soft tissues of your leg. Swelling may also appear as a swollen ridge along a blood vessel that you can feel.

- Pain in your leg that gets worse when you stand or walk. This is especially important if there is also swelling or redness in your leg.

Blood clots in the deep veins of the leg are the most common cause of pulmonary embolism. For more information on these types of blood clots, see the topic Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Who to see

Health professionals who can diagnose pulmonary embolism include:

- An emergency room doctor.

- An internal medicine doctor (internist).

- A family medicine doctor.

- A nurse practitioner or physician assistant.

- A pulmonologist.

- A cardiologist.

- A surgeon. This is most often a general surgeon, an orthopedic (bone) surgeon, or a vascular (vein) surgeon.

- An obstetrician (if pulmonary embolism is pregnancy-related).

Exams and Tests

Diagnosing pulmonary embolism is difficult, because there are many other medical conditions, such as a heart attack or an anxiety attack, that can cause similar symptoms.

Diagnosis depends on an accurate and thorough medical history and ruling out other conditions. Your doctor will need to know about your symptoms and risk factors for pulmonary embolism. This information, combined with a careful physical exam, will point to the initial tests that are best suited to diagnose a deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

Tests that are often done if you have shortness of breath or chest pain include:

- A chest X-ray. Results may rule out an enlarged heart or pneumonia as a cause of your symptoms. If the chest X-ray is normal, you may need further testing.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG, ECG). The electrical activity of the heart is recorded with this test. EKG results will help rule out a possible heart attack.

Further testing may include:

- D-dimer. A D-dimer blood test measures a substance that is released when a blood clot breaks up. D-dimer levels are usually high in people with pulmonary embolism.

- CT (computed tomography) scan or CT angiogram. These tests might be done to look for a pulmonary embolism or for a blood clot that may cause a pulmonary embolism.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This test may be used to view clots in the lungs.

- Doppler ultrasound. A Doppler ultrasound test uses reflected sound waves to determine whether a blood clot is present in the large veins of the legs.

- Echocardiogram (echo). This test detects abnormalities in the size or function of the heart’s right ventricle, which may be a sign of pulmonary embolism.

- Ventilation-perfusion scanning. This test scans for abnormal blood flow through the lungs after a radioactive tracer has been injected and you breathe a radioactive gas.

- Pulmonary angiogram. This invasive test is done only in rare cases to diagnose pulmonary embolism.

After your doctor has determined that you have a pulmonary embolism, other tests can help guide treatment and suggest how well you will recover. These tests may include:

- A blood test to check the level of the hormone brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Higher levels of BNP mean your heart is under increased stress.

- A blood test to look at the level of the protein troponin. Higher levels of troponin can mean there is damage to your heart muscle.

Treatment Overview

Treatment of pulmonary embolism focuses on preventing future pulmonary embolism by using anticoagulant medicines. Anticoagulants prevent existing blood clots from growing larger and help prevent new ones from developing.

If symptoms are severe and life-threatening, immediate and sometimes aggressive treatment is needed. Aggressive treatment may include thrombolytic medicines, which can dissolve a blood clot quickly but also increase the risk of severe bleeding. Another option for life-threatening, large pulmonary embolism is to remove the clot. This is called an embolectomy. An embolectomy is done during a surgery or minimally invasive procedure.

Some people may also benefit from having a vena cava filter inserted into the large central vein of the body. This filter can help prevent blood clots from reaching the lungs. This filter might be used if you have problems taking an anticoagulant.

Prevention

Daily use of anticoagulant medicines may help prevent recurring pulmonary embolism by stopping new blood clots from forming and stopping existing clots from growing.

The risk of forming another blood clot is highest in the weeks after the first episode of pulmonary embolism. This risk decreases over time. But the risk remains high for months and sometimes years, depending upon what caused the pulmonary embolism. People with recurrent blood clots and/or pulmonary embolism may have to take anticoagulants daily for the rest of their lives. Anticoagulant medicines also are often used for people who are not active due to illness or injury, or people who are having surgery on the legs, hips, belly, or brain.

Other preventive methods may also be used, such as:

- Getting you moving shortly after surgery.

- Wearing compression stockings to help prevent leg deep vein thrombosis if you are at increased risk for this condition.

Take steps to prevent blood clots from travel, such as walking around every hour. Because of long periods of inactivity, you are at higher risk for blood clots when you are traveling.

If you are already at high risk for pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis, talk to your doctor before taking a long flight or car trip. Ask if you need to take any special precautions to prevent blood clots during travel.

Home Treatment

Home treatment is not recommended for initial treatment for pulmonary embolism. But it is important for preventing more clots from developing and causing a deep vein thrombosis, which can lead to recurring pulmonary embolism.

Measures that reduce your risk for developing a deep vein thrombosis include the following:

- Take anticoagulant medicines exactly as prescribed.

- Exercise. Keep blood moving in your legs by pointing your toes up toward your head so that your calves are stretched, then relaxing. Repeat. This exercise is especially important when you are sitting for long periods of time, for example, on long driving trips or airplane flights.

- Get up out of bed as soon as possible after an illness or surgery. It is very important to get moving as soon as you are able. If you cannot get out of bed, do the leg exercises described above every hour to keep the blood moving through your legs.

- Quit smoking.

- Wear compression stockings to help prevent leg deep vein thrombosis if you are at increased risk for this condition.

For more information on how to prevent clots from developing, see the topic Deep Vein Thrombosis.

Medications

Medicines can help prevent repeated episodes of pulmonary embolism by preventing new blood clots from forming or preventing existing clots from getting larger.

Anticoagulants

Anticoagulants are prescribed when pulmonary embolism is diagnosed or strongly suspected.

You’ll likely take an anticoagulant for at least 3 months after pulmonary embolism to reduce the risk of having another blood clot.footnote 2 Treatment with anticoagulants may continue throughout your life if the risk of having another pulmonary embolism remains high.

Different types of anticoagulants are used to treat pulmonary embolism. Talk with your doctor to decide which medicine is right for you.

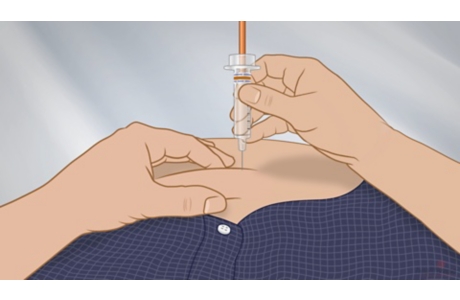

In the hospital, you might be given an anticoagulant as a shot or through an IV. After you go home, you might give yourself shots for a few days. For the long term, you’ll likely take a pill.

Anticoagulants include:

- Apixaban.

- Dabigatran.

- Edoxaban.

- Heparin.

- Rivaroxaban.

- Warfarin.

Safety tips for anticoagulants

If you take an anticoagulant, you can take steps to prevent bleeding. This includes preventing injuries and getting regular blood tests if needed.

Thrombolytics

Clot-dissolving (thrombolytic) medicines are not commonly used to treat pulmonary embolism. Although they can quickly dissolve a blood clot, thrombolytics also greatly increase the risk of serious bleeding. They are sometimes used to treat a life-threatening pulmonary embolism.

Surgery

The removal of a clot is called an embolectomy. An embolectomy might be done during a surgery. Or it might be done with a minimally invasive procedure that uses a catheter (a thin tube that is guided through a blood vessel). This type of treatment for pulmonary embolism is used only in rare cases. It is considered for people who can’t have other kinds of treatment or those whose clot is so dangerous that they can’t wait for medicine to work. An embolectomy also may be an option for a person whose condition is stable but who shows signs of significant reduced blood flow in the pulmonary artery.

What to think about

Surgery increases the risk of forming new blood clots that can cause another pulmonary embolism.

Other Treatment

If surgery or medicines are not options, other methods of preventing pulmonary embolism may be considered, such as a vena cava filter.

Other treatment choices

A vena cava filter may be inserted in the large central vein that passes through the abdomen and returns blood from the body to the heart (vena cava). This filter can prevent blood clots in the leg or pelvic veins from traveling to the lungs and heart. These filters may be permanent or removable.

What to think about

Vena cava filters aren’t typically recommended as the first treatment for pulmonary embolism. But they may be used in some people. For example, they may be used if a person cannot take anticoagulant medicine.

Vena cava filters can cause serious health problems if they break or become blocked with one or more blood clots.

References

Citations

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Available online: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/deepvein/index.html.

- Guyatt GH, et al. (2012). Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed.—American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest, 141(2, Suppl): 7S–47S.

Other Works Consulted

- Advice for travelers (2012). Treatment Guidelines From The Medical Letter, 10(118): 45–56.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2009). Your Guide to Preventing and Treating Blood Clots. (AHRQ Publication No. 08-0058-A). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available online: http://www.ahrq.gov/consumer/bloodclots.htm.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2007, reaffirmed in 2011). Prevention of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 84. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 110(2): 429–440.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2011). Thromboembolism in pregnancy. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 123. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 118(3): 718–729.

- Fedullo PF (2011). Pulmonary embolism. In V Fuster et al., eds., Hurst’s The Heart, 13th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1634–1654. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Goldhaber SZ (2015). Pulmonary embolism. In DL Mann et al., eds., Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 10th ed., vol. 2, pp. 1664–1681. Philadelphia: Saunders.

- Guyatt GH, et al. (2012). Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed.—American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest, 141(2, Suppl): 7S–47S.

- Jaff MR, et al. (2011). Management of massive and submassive pulmonary embolism, iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis, and chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 123(16): 1788–1830.

- Kearon C, et al. (2016). Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest, 149(2): 315–352. DOI: 10.1016/j.chest.2015.11.026. Accessed March 1, 2016.

- McManus RJ, et al. (2011). Thromboembolism, search date June 2010. BMJ Clinical Evidence. Available online: http://www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Raja AS, et al. (2015). Evaluation of patients with suspected acute pulmonary embolism: Best practice advice from the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(9): 701–711. DOI: 10.7326/M14-1772. Accessed November 12, 2015.

- Sobieszczyk P (2012). Catheter-assisted pulmonary embolectomy. Circulation, 126(15): 1917–1922.

- Tapson VF, Becker RC (2007). Venous thromboembolism. In EJ Topol et al., eds., Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, 3rd ed., pp. 1569–1584. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2008). The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Available online: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/calls/deepvein/index.html.

- Waldron B, Moll S (2014). A patient’s guide to recovery after deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Circulation, 129(17): e477–e479. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.006285. Accessed October 24, 2014.

- Weitz JL (2016). Pulmonary embolism. In L Goldman, A Schafer, eds., Goldman-Cecil Medicine, 25th ed., vol. 1, pp. 620–627. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Current as of: September 26, 2018

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Martin J. Gabica MD – Family Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Jeffrey S. Ginsberg MD – Hematology

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.