COPD’s Effect on the Lungs

Topic Overview

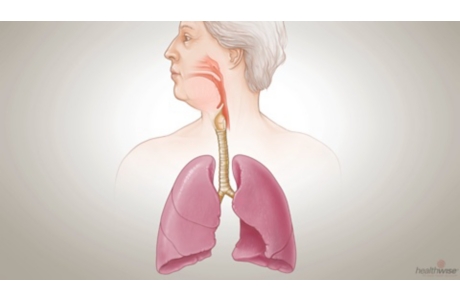

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) slowly damages the lungs and affects how you breathe.

COPD’s effect on breathing

In COPD, the airways of the lungs (bronchial tubes) become inflamed and narrowed. They tend to collapse when you breathe out and can become clogged with mucus. This reduces airflow through the bronchial tubes, a condition called airway obstruction, making it difficult to move air in and out of the lungs.

The inflammation of the bronchial tubes makes the nerves in the lungs very sensitive. In response to irritation, the body forces air through the airways by a rapid and strong contraction of the muscles of respiration—a cough. The rapid movement of air in the breathing tubes helps remove mucus from the lungs into the throat. People with COPD often cough a great deal in the morning after a large amount of mucus has built up overnight (smoker’s cough).

The oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange

The lungs are where the blood picks up oxygen to deliver throughout the body and where it disposes of carbon dioxide that is a by-product of the body processes. COPD affects this process.

Emphysema can lead to destruction of the alveoli, the tiny air sacs that allow oxygen to get into the blood. Their destruction leads to the formation of large air pockets in the lung called bullae. These bullae do not exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide like normal lung tissue. Also, the bullae can become very large. Normal lung tissue next to the bullae cannot expand properly, reducing lung function.

Chronic bronchitis affects the oxygen and carbon dioxide exchange because the airway swelling and mucus production can also narrow the airways and reduce the flow of oxygen-rich air into the lung and carbon dioxide out of the lung.

The damage to the alveoli and airways makes it harder to exchange carbon dioxide and oxygen during each breath. Decreased levels of oxygen in the blood and increased levels of carbon dioxide cause the breathing muscles to contract harder and faster. The nerves in the muscles and lungs sense this increased activity and report it to the brain. As a result, you feel short of breath.

Current as of: June 9, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson, MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney, MD – Family Medicine & Ken Y. Yoneda, MD – Pulmonology, Critical Care Medicine

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.