COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease)

Topic Overview

What is chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)?

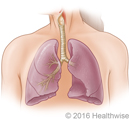

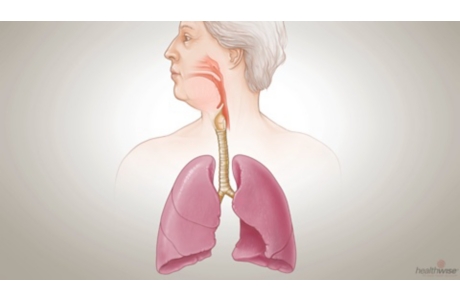

COPD is a lung disease that makes it hard to breathe. It is caused by damage to the lungs over many years, usually from smoking.

COPD is often a mix of two diseases:

- Chronic bronchitis (say “bron-KY-tus”). In chronic bronchitis, the airways that carry air to the lungs (bronchial tubes) get inflamed and make a lot of mucus. This can narrow or block the airways, making it hard for you to breathe.

- Emphysema (say “em-fuh-ZEE-muh”). In a healthy person, the tiny air sacs in the lungs are like balloons. As you breathe in and out, they get bigger and smaller to move air through your lungs. But with emphysema, these air sacs are damaged and lose their stretch. Less air gets in and out of the lungs, which makes you feel short of breath.

COPD gets worse over time. You can’t undo the damage to your lungs. But you can take steps to prevent more damage and to feel better.

What causes COPD?

COPD is almost always caused by smoking. Over time, breathing tobacco smoke irritates the airways and destroys the stretchy fibers in the lungs.

Other things that may put you at risk include breathing chemical fumes, dust, or air pollution over a long period of time. Secondhand smoke also may damage the lungs.

It usually takes many years for the lung damage to start causing symptoms, so COPD is most common in people who are older than 60.

You may be more likely to get COPD if you had a lot of serious lung infections when you were a child. People who get emphysema in their 30s or 40s may have a disorder that runs in families, called alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. But this is rare.

What are the symptoms?

The main symptoms are:

- A long-lasting (chronic) cough.

- Mucus that comes up when you cough.

- Shortness of breath that gets worse when you exercise.

As COPD gets worse, you may be short of breath even when you do simple things like get dressed or fix a meal. It gets harder to eat or exercise, and breathing takes much more energy. People often lose weight and get weaker.

At times, your symptoms may suddenly flare up and get much worse. This is called a COPD exacerbation (say “egg-ZASS-er-BAY-shun”). An exacerbation can range from mild to life-threatening. The longer you have COPD, the more severe these flare-ups will be.

How is COPD diagnosed?

To find out if you have COPD, a doctor will:

- Do a physical exam and listen to your lungs.

- Ask you questions about your past health and whether you smoke or have been exposed to other things that can irritate your lungs.

- Have you do breathing tests, including spirometry, to find out how well your lungs work.

- Do chest X-rays and other tests to help rule out other problems that could be causing your symptoms.

- Do an Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT) blood test. AAT is a protein your body makes that helps protect the lungs. People who have a low AAT are more likely to get emphysema. This test only needs to be done once.

If there is a chance you could have COPD, it is very important to find out as soon as you can. This gives you time to take steps to slow the damage to your lungs.

How is it treated?

The best way to slow COPD is to quit smoking. This is the most important thing you can do. It is never too late to quit. No matter how long you have smoked or how serious your COPD is, quitting smoking can help stop the damage to your lungs.

Your doctor can prescribe treatments that may help you manage your symptoms and feel better.

- Medicines can help you breathe easier. Most of them are inhaled so they go straight to your lungs. If you get an inhaler, it is very important to use it just the way your health provider shows you.

- A lung (pulmonary) rehab program can help you learn to manage your disease. A team of health professionals can provide counseling and teach you how to breathe easier, exercise, and eat well.

- In time, you may need to use oxygen some or most of the time.

People who have COPD are more likely to get lung infections, so you will need to get a flu vaccine every year. You should also get a pneumococcal shot. It may not keep you from getting pneumonia. But if you do get pneumonia, you probably won’t be as sick.

How can you live well with COPD?

There are many things you can do at home to stay as healthy as you can.

- Avoid things that can irritate your lungs, such as smoke and air pollution.

- Use an air filter in your home.

- Get regular exercise to stay as strong as you can.

- Eat well so you can keep up your strength. If you are losing weight, ask your doctor or dietitian about ways to make it easier to get the calories you need.

Dealing with flare-ups: As COPD gets worse, you may have flare-ups when your symptoms quickly get worse and stay worse. It is important to know what to do if this happens. Your doctor may give you an action plan and medicines to help you breathe if you have a flare-up. But if the attack is severe, you may need to go to the emergency room or call 911.

Managing depression and anxiety: Knowing that you have a disease that gets worse over time can be hard. It’s common to feel sad or hopeless sometimes. Having trouble breathing can also make you feel very anxious. If these feelings last, be sure to tell your doctor. Counseling, medicine, and support groups can help you cope.

Health Tools

Health Tools help you make wise health decisions or take action to improve your health.

- Breathing Exercises: Using a Manual Incentive Spirometer

- Breathing Problems: Using a Dry Powder Inhaler

- Breathing Problems: Using a Metered-Dose Inhaler

- COPD: Avoiding Weight Loss

- COPD: Avoiding Your Triggers

- COPD: Clearing Your Lungs

- COPD: Keeping Your Diet Healthy

- COPD: Learning to Breathe Easier

- COPD: Using Exercise to Feel Better

- Oxygen Therapy: Using Oxygen at Home

Cause

COPD is most often caused by smoking. Most people with COPD are long-term smokers, and research shows that smoking cigarettes increases the risk of getting COPD.

COPD is often a mix of two diseases: chronic bronchitis and emphysema. Both of these diseases are caused by smoking. Although you can have either chronic bronchitis or emphysema, people more often have a mixture of both diseases.

Other causes

Other possible causes of COPD include:

- Long-term exposure to lung irritants such as industrial dust and chemical fumes.

- Preterm birth that leads to lung damage (neonatal chronic lung disease).

- Inherited factors (genes), including alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency. This is a rare condition in which your body may not be able to make enough of a protein (alpha-1 antitrypsin) that helps protect the lungs from damage. People who have this disorder and who smoke generally start to have symptoms of emphysema in their 30s or 40s. Those who have this disorder but don’t smoke generally start to have symptoms in their 80s.

Symptoms

When you have COPD:

- You have a cough that won’t go away.

- You often cough up mucus.

- You are often short of breath, especially when you exercise.

- You may feel tightness in your chest.

COPD exacerbation

Many people with COPD have attacks called flare-ups or exacerbations (say “egg-ZASS-er-BAY-shuns”). This is when your usual symptoms quickly get worse and stay worse. A COPD flare-up can be dangerous, and you may have to go to the hospital.

Symptoms include:

- Coughing up more mucus than usual.

- A change in the color or thickness of that mucus.

- More shortness of breath than usual.

- Greater tightness in your chest.

These attacks are most often caused by infections—such as acute bronchitis and pneumonia—and air pollution.

Work with your doctor to make a plan for dealing with a COPD flare-up. If you are prepared, you may be able to get it under control. Try not to panic if you start to have a flare-up. Quick treatment at home may help you manage serious breathing problems.

What Increases Your Risk

Tobacco smoking

Tobacco smoking is the most important risk factor for COPD. Compared to smoking, other risks are minor.

- Pipe and cigar smokers have less risk of getting COPD than cigarette smokers. But they still have more risk than nonsmokers.

- The risk for COPD increases with both the amount of tobacco you smoke each day and the number of years you have smoked.

To learn more, see the topic Quitting Smoking.

Other risks

Family history

Some people may be more at risk than others for getting the disease, especially if they have low levels of the protein alpha-1 antitrypsin (alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency), a disorder that runs in families.

Preterm birth

Preterm babies usually need to have long-term oxygen therapy because their lungs are not fully developed. This therapy can cause lung damage (neonatal chronic lung disease) that can increase the risk for COPD later in life.

Asthma

Asthma and COPD are different diseases, even though both of them involve breathing problems. People with asthma may have a greater risk for getting COPD, but the reasons for this are not fully understood.

Risks in the environment

- Outside air pollution. Air pollution may make COPD worse. It may increase the risk of a flare-up, or COPD exacerbation, when your symptoms quickly get worse and stay worse. Try not to be outside when air pollution levels are high.

- Indoor air pollution. Have good ventilation in your home to avoid indoor air pollution.

- Secondhand smoke. It is not yet known whether secondhand smoke can lead to COPD. But a large study showed that children who were exposed to secondhand smoke were more likely to get emphysema than children who weren’t exposed. And people who are exposed to secondhand smoke for a long time are more likely to have breathing problems and respiratory diseases. footnote 1

- Occupational hazards. If your work exposes you to chemical fumes or dust, use safety equipment to reduce the amount of fumes and dust you breathe.

When to Call a Doctor

Call 911 or other emergency services now if:

- Breathing stops.

- Moderate to severe difficulty breathing occurs. This means a person may have trouble talking in full sentences or breathing during activity.

- Severe chest pain occurs, or chest pain is quickly getting worse.

- You cough up large amounts of bright red blood.

Call your doctor immediately or go to the emergency room if you have been diagnosed with COPD and you:

- Cough up a couple of tablespoons of blood.

- Have shortness of breath or wheezing that is quickly getting worse.

- Start having new chest pain.

- Are coughing more deeply or more often, especially if you notice an increase in mucus (sputum) or a change in the color of the mucus you cough up.

- Have increased swelling in your legs or belly.

- Have a high fever [over 101°F (38.3°C)].

- Develop flu-like symptoms.

If your symptoms (cough, mucus, and/or shortness of breath) suddenly get worse and stay worse, you may be having a COPD flare-up, or exacerbation. Quick treatment for a flare-up may help keep you out of the hospital.

Call your doctor soon for an appointment if:

- Your medicine is not working as well as it had been.

- Your symptoms are slowly getting worse, and you have not seen a doctor recently.

- You have a cold and:

- Your fever lasts longer than 2 to 3 days.

- Breathlessness occurs or becomes noticeably worse.

- Your cough gets worse.

- You have not been diagnosed with COPD but are having symptoms. A history of smoking (even in the past) greatly increases the likelihood that symptoms are from COPD.

- You cough up any amount of blood.

Talk to your doctor

If you have been diagnosed with COPD, talk with your doctor at your next regular appointment about:

- Help to stop smoking. To review tips on how to stop smoking, see the topic Quitting Smoking.

- A yearly flu vaccine.

- A pneumococcal vaccine. Usually, people need only one shot. But doctors recommend a second one for some people who got their first shot before they turned 65.

- An exercise program or pulmonary rehabilitation.

- Any updates of your medicines or treatment that you may need.

Who to see

Health professionals who can diagnose COPD and provide a basic treatment plan include:

You may need to see a specialist in lung disease, called a pulmonologist (say “pull-muh-NAWL-uh-jist”), if:

- Your diagnosis of COPD is uncertain or hard to make because you have diseases with similar symptoms.

- You have unusual symptoms that are not usually seen in people with COPD.

- You are younger than 50 and/or have no history or a short history of cigarette smoking.

- You have to go to the hospital often because of sudden increases in shortness of breath.

- You need long-term oxygen therapy or corticosteroid therapy.

- You and your doctor are considering surgery, such as a lung transplant or lung volume reduction.

Exams and Tests

To diagnose COPD, your doctor will probably do the following tests:

- Medical history and physical exam. These will give your doctor important information about your health.

- Lung function tests, including an FEV1 test. These tests measure the amount of air in your lungs and the speed at which air moves in and out. Spirometry is the most important of these tests.

- Chest X-ray. This helps rule out other conditions with similar symptoms, such as lung cancer.

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin (AAT)test.AAT is a protein your body makes that helps protect the lungs. People who have a low AAT are more likely to get emphysema.

Tests done as needed

- Arterial blood gas test. This test measures how much oxygen, carbon dioxide, and acid is in your blood. It helps your doctor decide whether you need oxygen treatment.

- Oximetry. This test measures the oxygen saturation in the blood. It can be useful in finding out whether oxygen treatment is needed, but it provides less information than the arterial blood gas test.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG) or echocardiogram. These tests may find certain heart problems that can cause shortness of breath.

- Transfer factor for carbon monoxide. This test looks at whether your lungs have been damaged, and if so, how much damage there is and how bad your COPD might be.

Tests rarely done

- A CT scan. This gives doctors a detailed picture of the lungs.

Regular checkups

Because COPD is a disease that keeps getting worse, it is important to schedule regular checkups with your doctor. Checkups may include:

- Spirometry.

- Arterial blood gas test.

- X-rays or ECGs.

Tell your doctor about any changes in your symptoms and whether you have had any flare-ups. Your doctor may change your medicines based on your symptoms.

Early detection

The sooner COPD is diagnosed, the sooner you can take steps to slow down the disease and keep your quality of life for as long as possible. Screening tests help your doctor diagnose COPD early.

Talk to your doctor about COPD screening if you:

- Are a smoker or an ex-smoker.

- Have had serious asthma symptoms for a long time, and they have not improved with treatment.

- Have a family history of emphysema.

- Have a job where you are exposed to a lot of chemicals or dust.

- Have symptoms such as repeated chest or lung infections, increasing shortness of breath or a chronic cough, and coughing up sputum.

If you have symptoms and risk factors, screening tests can help diagnose COPD.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) doesn’t recommend COPD screening for adults who are not at high risk for COPD.footnote 2 And some experts recommend that screening be done only for people who have symptoms of a lung problem.footnote 2

Treatment Overview

The goals of treatment for COPD are to:

- Slow down the disease by quitting smoking and avoiding triggers, such as air pollution.

- Limit your symptoms, such as shortness of breath, with medicines.

- Increase your overall healthwith regular activity.

- Prevent and treat flare-ups with medicines and other treatment.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (rehab) can help you meet these goals. It helps train your mind, muscles, and heart to get the most out of damaged lungs. The program involves a team of health professionals who help prevent or manage the problems caused by COPD. Rehab typically combines exercise, breathing therapy, advice for eating well, and other education.

Self-care

Much of the treatment for COPD includes things you can do for yourself.

Quitting smoking is the most important thing you can do to slow the disease and improve your quality of life.

Other things you can do that really make a difference including eating well, staying active, and avoiding triggers. To learn more, see Living With COPD.

Medicines

The medicines used to treat COPD can be long-acting to help prevent symptoms or short-acting to help relieve them. To learn more, see Medications.

Other treatment you may need

If COPD gets worse, you may need other treatment, such as:

- Oxygen treatment. This involves getting extra oxygen through a face mask or through a small tube that fits just inside your nose. It can be done in the hospital or at home.

- Treatment for muscle weakness and weight loss. Many people with severe COPD have trouble keeping their weight up and their bodies strong. This can be treated by paying attention to eating regularly and well.

- Help with depression. COPD can affect more than your lungs. It can cause stress, anxiety, and depression. These things take energy and can make your COPD symptoms worse. But they can be treated. If you feel very sad or anxious, call your doctor.

- Surgery. Surgery is rarely used for COPD. It’s only considered for people who have severe COPD that has not improved with other treatment.

Dealing with flare-ups

COPD flare-ups, or exacerbations, are when your symptoms—shortness of breath, cough, and mucus production—quickly get worse and stay worse.

Work with your doctor to make a plan for dealing with a COPD flare-up. If you are prepared, you may be able to get it under control. Don’t panic if you start to have one. Quick treatment at home may help you prevent serious breathing problems.

A flare-up can be life-threatening, and you may need to go to your doctor’s office or to a hospital. Treatment for flare-ups includes:

- Quick-relief medicines to help you breathe.

- Anticholinergics (such as ipratropium or tiotropium)

- Oral corticosteroids (such as methylprednisolone or prednisone)

- Beta2-agonists (such as albuterol or metaproterenol)

- Machines to help you breathe. The use of a machine to help with breathing is called mechanical ventilation. Ventilation is used only if medicine isn’t helping you and your breathing is getting very difficult.

- Noninvasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) forces air into your lungs through a face mask.

- With invasive ventilation, a breathing tube is inserted into your windpipe, and a machine forces air into your lungs.

- Oxygen to help you breathe. Oxygen treatment can be done in the hospital or at home.

- Antibiotics. These medicines are used when a bacterial lung infection is considered likely. People with COPD have a higher risk of pneumonia and frequent lung infections. These infections often lead to COPD exacerbations, or flare-ups, so it’s important to try to avoid them.

Prevention

Don’t smoke

The best way to keep COPD from starting or from getting worse is to not smoke.

There are clear benefits to quitting, even after years of smoking. When you stop smoking, you slow down the damage to your lungs. For most people who quit, loss of lung function is slowed to the same rate as a nonsmoker’s.

Stopping smoking is especially important if you have low levels of the protein alpha-1 antitrypsin. People who have an alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency may lower their risk for severe COPD if they get regular shots of alpha-1 antitrypsin. Family members of someone with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency should be tested for the condition.

Avoid bad air

Other airway irritants (such as air pollution, chemical fumes, and dust) also can make COPD worse, but they are far less important than smoking in causing the disease.

Get vaccines

Flu vaccines

If you have COPD, you need to get a flu vaccine every year. When people with COPD get the flu, it often turns into something more serious, like pneumonia. A flu vaccine can help prevent this from happening.

Also, getting regular flu vaccines may lower your chances of having COPD flare-ups.

Pneumococcal vaccine

People with COPD often get pneumonia. Getting a shot can help keep you from getting very ill with pneumonia. People younger than 65 usually need only one shot. But doctors sometimes recommend a second shot for some people who got their first shot before they turned 65. Talk with your doctor about whether you need a second shot. Two different types of pneumococcal vaccines are recommended for people ages 65 and older.

Pertussis vaccine

Pertussis (also called whooping cough) can increase the risk of having a COPD flare-up. So making sure you are current on your pertussis vaccinations may help control COPD.

Ongoing Concerns

COPD gradually gets worse over time.

Shortness of breath gets worse as COPD gets worse.

- If you are diagnosed early, before you have a lot of lung damage, you may have very mild symptoms, even when you are active.

- If you are diagnosed later, you may have already lost much of your lung function.

- If you are active, you may be short of breath during activities that didn’t used to cause this problem.

- If you are not very active, you may not notice how much shortness of breath you have until your COPD gets worse.

- If you have had COPD for many years, you may be short of breath even when you are at rest. Even simple activities may cause very bad shortness of breath.

It’s very important to stop smoking. If you keep smoking after being diagnosed with COPD, the disease will get worse faster, your symptoms will be worse, and you will have a greater risk of having other serious health problems.

The lung damage that causes symptoms of COPD doesn’t heal and cannot be repaired. But if you have mild to moderate COPD and you stop smoking, you can slow the rate at which breathing becomes more difficult. You will never be able to breathe as well as you would have if you had never smoked, but you may be able to postpone or avoid more serious problems with breathing.

Complications

Other health problems from COPD may include:

- More frequentlung infections, such as pneumonia.

- An increased risk of thinning bones(osteoporosis), especially if you use oral corticosteroids.

- Problems with weight. If chronic bronchitis is the main part of your COPD, you may need to lose weight. If emphysema is your main problem, you may need to gain weight and muscle mass.

- Heart failure affecting the right side of the heart (cor pulmonale).

- A collapsed lung (pneumothorax). COPD can damage the lung’s structure and allow air to leak into the chest cavity.

- Sleep problems because you are not getting enough oxygen into your lungs.

Palliative care

Palliative care is a kind of care for people who have a serious illness. It’s different from care to cure your illness. Its goal is to improve your quality of life—not just in your body but also in your mind and spirit. You can have this care along with treatment to cure your illness.

Palliative care providers will work to help control pain or side effects. They may help you decide what treatment you want or don’t want. And they can help your loved ones understand how to support you.

If you’re interested in palliative care, talk to your doctor.

For more information, see the topic Palliative Care.

End-of-life care

Treatment for COPD is getting better and better at helping people live longer. But COPD is a disease that keeps getting worse, and it can be fatal.

A time may come when treatment for your illness no longer seems like a good choice. This can be because the side effects, time, and costs of treatment are greater than the promise of cure or relief. But you can still get treatment to make you as comfortable as possible during the time you have left. You and your doctor can decide when you may be ready for hospice care.

For more information, see the topics:

Living With COPD

When you manage COPD, you:

- Quit smoking.

- Take steps to improve your ability to breathe.

- Eat well and stay active.

- Learn all you can about COPD.

- Get support from your family and friends.

Quit smoking

It’s never too late to quit smoking. No matter how long you have had COPD or how serious it is, quitting smoking will help slow down the disease and improve your quality of life.

Although lung damage that already has occurred doesn’t reverse, quitting smoking can slow down how quickly your COPD symptoms get worse.

One Man’s Story: Ned, 56 “I tried to quit cold turkey, but after just a few days I could tell that wasn’t going to work. I realized that I needed to try something else. So I tried the patch, and that made a big difference. I can feel a difference in my breathing. And I feel hopeful that quitting will give me a few more years on my feet.”— Ned |

You may think that nothing can help you quit. But today there are several treatments shown to be very good at helping people stop smoking. They include:

- Nicotine replacement therapy.

- The medicines bupropion (Wellbutrin or Zyban) and varenicline (Chantix).

- Support groups.

Today’s medicines offer lots of help for people who want to quit. You will double your chances of quitting even if medicine is the only treatment you use to quit, but your odds get even better when you combine medicine and other quit strategies, such as counseling.

For more information, see the topic Quitting Smoking.

Make breathing easier

Do all you can to make breathing easier.

- Avoid conditions that may irritate your lungs, such as indoor and outdoor air pollution, smog, cold dry air, hot humid air, and high altitudes.

- Conserve your energy. You may get more tasks done and feel better if you learn to save energy while doing chores and other activities. Take rest breaks and sit down whenever you can while you fold laundry, cook, and do other household tasks. An occupational or physical therapist can help you find ways to do everyday activities with less effort.

- Stay as active as possible, and get regular exercise. Try to do activities and exercises that build muscle strength and help your cardiovascular system. If you get out of breath, wait until your breathing returns to normal before continuing.

- Learn breath training techniques to improve airflow in and out of your lungs.

- Learn ways to clear your lungs that can help you save energy and oxygen.

- Discusspulmonary rehabilitation with your doctor.

- Take the medicines prescribed by your doctor. If you use an inhaler, be sure you know how to use it properly.

One Man’s Story: Cal, 66 “There was a time when I couldn’t take 10 steps without running out of breath. Now I walk an hour around my neighborhood every day—without needing my oxygen. I feel better than I have in years.”— Cal |

Eat well

Good nutrition is important to keep up your strength and health. Problems with muscle weakness and weight loss are common in people with severe COPD. It’s dangerous to become very underweight.

Seek education and support

Treating more than the disease and its symptoms is very important. You also need:

- Education. Educating yourself and your family about COPD and your treatment program helps you and your family cope with your lung disease.

- Counseling and support. Shortness of breath may reduce your activity level and make you feel socially isolated because you cannot enjoy activities with your family and friends. You should be able to lead a full life and be sexually active. Counseling and support groups can help you learn to live with COPD.

- A support network of family, friends, and health professionals. Learning that you have a disease that may shorten your life can trigger depression or grieving. Anxiety can make your symptoms worse and can trigger flare-ups or make them last longer. Support from family and friends can reduce anxiety and stress and make it easier to live with COPD.

- Your treatment plan. Following a treatment plan will make you feel better and less likely to become depressed. A self-reward system—such as a night out to eat after staying on your medicine and exercise schedule for a week—can help keep you motivated.

One Woman’s Story: Sarah, 67 “Not being the person I used to be—it makes me really sad sometimes. There are lots of days I don’t want to even get up, but then I think about taking my walk or seeing my friends, and I want get out there. COPD may slow me down, but it isn’t going to stop me.”— Sarah |

Medications

Medicine for COPD is used to:

- Reduce shortness of breath.

- Control coughing and wheezing.

- Prevent COPD flare-ups, also called exacerbations, or keep the flare-ups you do have from being life-threatening.

Most people with COPD find that medicines make breathing easier.

Some COPD medicines are used with devices called inhalers or nebulizers. It’s important to learn how to use these devices correctly. Many people don’t, so they don’t get the full benefit from the medicine.

Medicine choices

- Bronchodilators are used to open or relax your airways and help your shortness of breath.

- Short-acting bronchodilators ease your symptoms. They are considered a good first choice for treating stable COPD in a person whose symptoms come and go (intermittent symptoms). They include:

- Anticholinergics (such as ipratropium).

- Beta2-agonists (such as albuterol or levalbuterol).

- A combination of the two (such as a combination of albuterol and ipratropium).

- Long-acting bronchodilators help prevent breathing problems. They help people whose symptoms do not go away (persistent symptoms). They include:

- Anticholinergics (such as aclidinium, tiotropium, or umeclidinium).

- Beta2-agonists (such as formoterol or salmeterol).

- A combination of the two, or a combination of a beta2-agonist and a corticosteroid medicine.

- Short-acting bronchodilators ease your symptoms. They are considered a good first choice for treating stable COPD in a person whose symptoms come and go (intermittent symptoms). They include:

- Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE4) inhibitors are taken every day to help prevent COPD exacerbations. The only PDE4 inhibitor available is roflumilast (Daliresp).

- Corticosteroids(such as prednisone) may be used in pill form to treat a COPD flare-up or in an inhaled form to prevent flare-ups. They are often used if you also have asthma.

- Other medicines include methylxanthines, which generally are used for severe cases of COPD. They may have serious side effects, so they are not usually recommended.

Tips for using inhalers

The first time you use a bronchodilator, you may not notice much improvement in your symptoms. This doesn’t always mean that the medicine won’t help. Try the medicine for a while before you decide if it is working.

Many people don’t use their inhalers right, so they don’t get the right amount of medicine. Ask your health care provider to show you what to do. Read the instructions on the package carefully.

Most doctors recommend using spacers with metered-dose inhalers. But you should not use a spacer with a dry powder inhaler.

- Breathing Problems: Using a Metered-Dose Inhaler with or without a spacer

- Breathing Problems: Using a Dry Powder Inhaler

Surgery

Lung surgery is rarely used to treat COPD. Surgery is never the first treatment choice and is only considered for people who have severe COPD that has not improved with other treatment.

Surgery choices

- Lung volume reduction surgery removes part of one or both lungs, making room for the rest of the lung to work better. It is used only for some types of severe emphysema.

- Lung transplant replaces a sick lung with a healthy lung from a person who has just died.

- Bullectomy removes the part of the lung that has been damaged by the formation of large, air-filled sacs called bullae. This surgery is rarely done.

Other Treatment

Other treatment for COPD includes:

- Oxygen treatment. This treatment involves breathing extra oxygen through a face mask or through a tube inserted just inside your nose. It may ease shortness of breath. And it can help people with very bad COPD and low oxygen levels live longer.

- Ventilation devices. These are machines that help you breathe better or breathe for you. They are used most often in the hospital during COPD flare-ups.

- Alpha-1 antitrypsin injections (such as Aralast, Prolastin, or Zemaira). These medicines can help people who have alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

References

Citations

- Lovasi GS, et al. (2010). Association of environmental tobacco smoke exposure in childhood with early emphysema in adulthood among nonsmokers. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(1): 54–62.

- Qaseem A, et al. (2011). Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(3): 179–191.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Screening for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA, 315(13): 1372-1377. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2638.

Other Works Consulted

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (2017). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. http://goldcopd.org/gold-2017-global-strategy-diagnosis-management-prevention-copd. Accessed November 27, 2016.

- Criner GJ, Sternberg AL (2008). A clinician’s guide to the use of lung volume reduction surgery. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 5(4): 461–467.

- King DA, et al. (2008). Nutritional aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 5(4): 519–523.

- Qaseem A, et al. (2011). Diagnosis and management of stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, and European Respiratory Society. Annals of Internal Medicine, 155(3): 179–191.

Current as of: June 9, 2019

Author: Healthwise Staff

Medical Review:E. Gregory Thompson MD – Internal Medicine & Adam Husney MD – Family Medicine & Ken Y. Yoneda MD – Pulmonology

Chronic Bronchitis

Chronic Bronchitis Airways Inside the Lungs

Airways Inside the Lungs Emphysema

Emphysema Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular system Using a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer (Adult)

Using a metered-dose inhaler with a spacer (Adult) Lung Transplant

Lung Transplant Avoiding COPD Triggers

Avoiding COPD Triggers COPD: What Happens to Your Lungs

COPD: What Happens to Your Lungs COPD: Keeping Your Quality of Life

COPD: Keeping Your Quality of Life COPD: Take This Chance to Quit Smoking

COPD: Take This Chance to Quit Smoking COPD: You Can Still Be Active

COPD: You Can Still Be Active

This information does not replace the advice of a doctor. Healthwise, Incorporated, disclaims any warranty or liability for your use of this information. Your use of this information means that you agree to the Terms of Use. Learn how we develop our content.